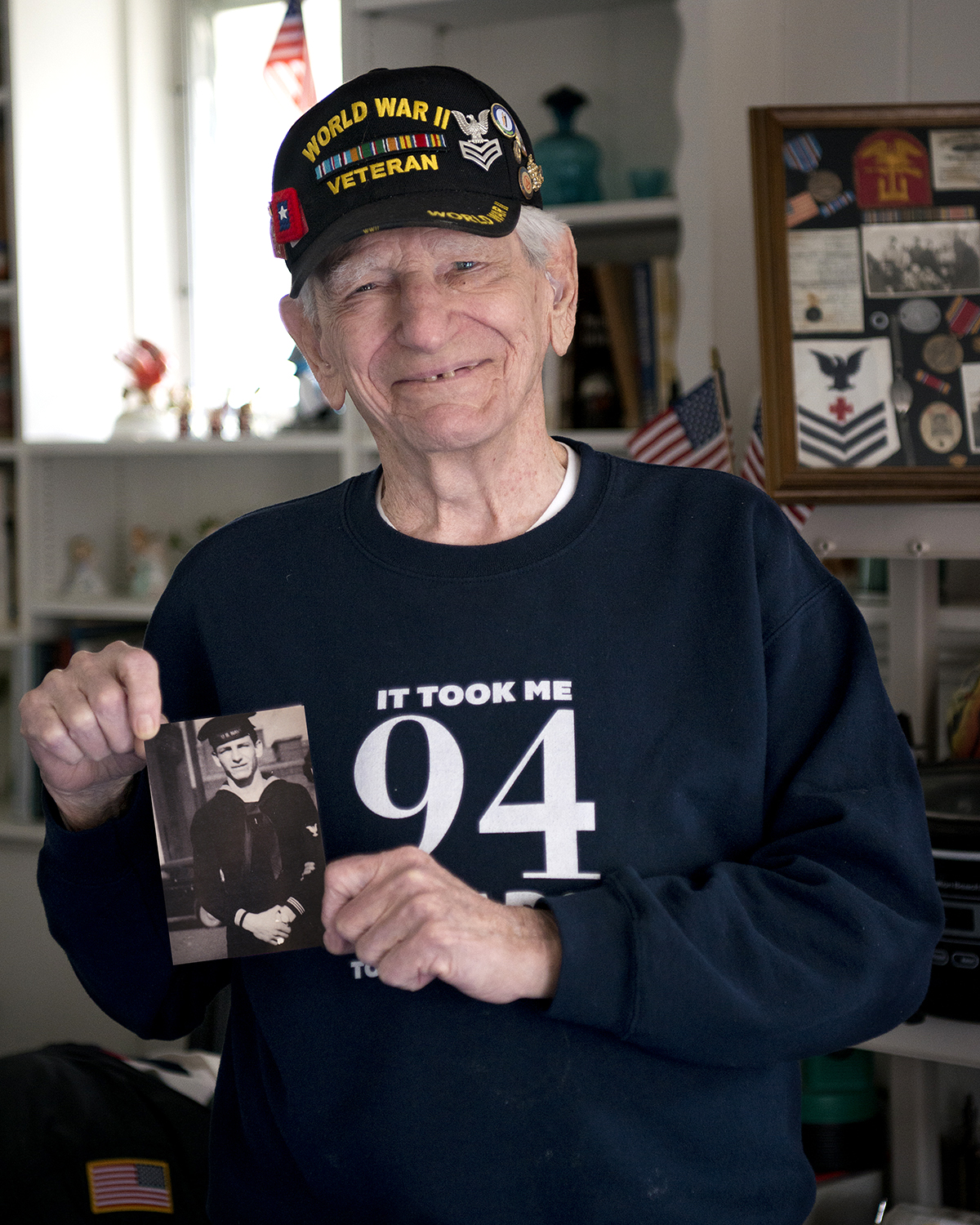

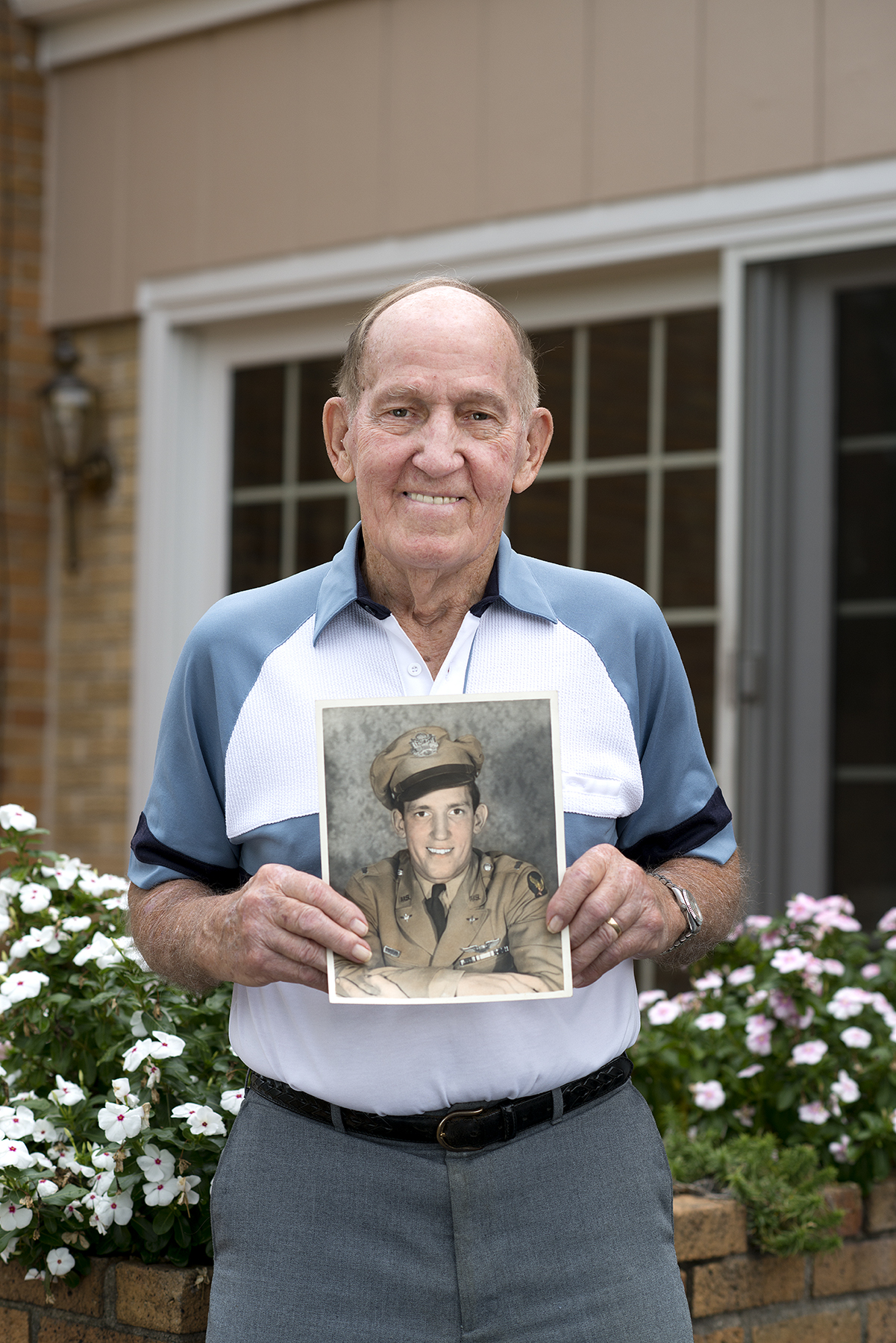

Chester Bishop

Chester Bishop was born in 1921 in Falmouth, Kentucky. He grew up on a farm there where his family had crop fields and raised cows for milk. He joined the infantry after hearing a neighbor girl talking about how her brother had been killed in North Africa. This caused Chester to want to join up. He trained in the 94th Infantry Division (Known as Patton's Golden Nugget) in Patton's Third Army and was in 209 days of combat in the Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe Campaigns.

He hesitantly reflected on an attack his platoon made on a German Pillbox near the town of Merzig, Germany on the Saar River. "We attacked a pillbox. We didn't know they had cover fire from a mortar team at the pillbox. Our Platoon came up over the burm, up and down like this, you know? *motions up and down with his hand in a wave* So Jack Osment went up there about four feet to my left and eight feet ahead of me. All the sudden I felt the air from the mortar shell and it hit in front of me and got Jack. One piece of shrapnel went through the back of his helmet, but didn't hit his head and he was all full of shrapnel up and down his side. I got nothin'. Jack was my machine gunner and I carried my M1 Rifle and his ammunition in dinner buckets (ammo boxes). There were 250 rounds per dinner bucket. I was the ammo carrier. I was with my machine gunner all of the time, I went where he went and dug in wherever he had to. We had two gunners and two ammo bearers. I was one and the other ammo bearer got killed that day. I don't know how I made it."

Chester was kind enough to share that short story with me. He told me that with all of his combat experience in the four campaigns he participated in with the 94th Infantry Div. he had tons of terrible stories that he didn't want to think about or talk about, but he at least wanted to tell me one that wasn't as bad as the others.

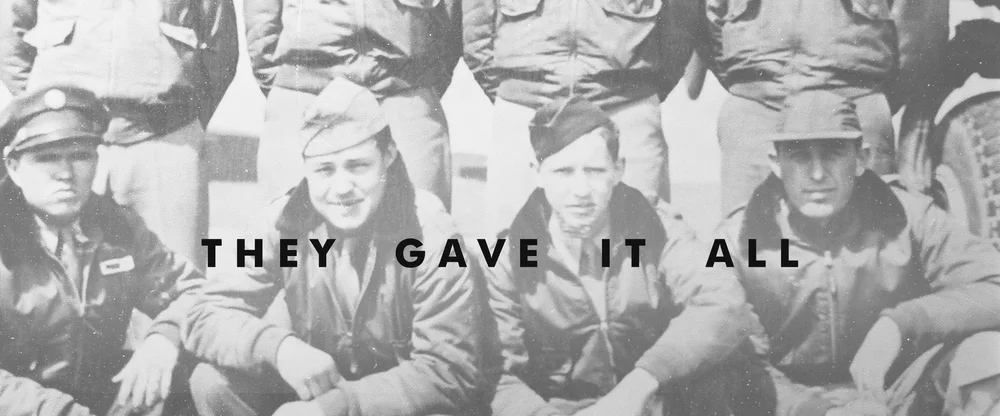

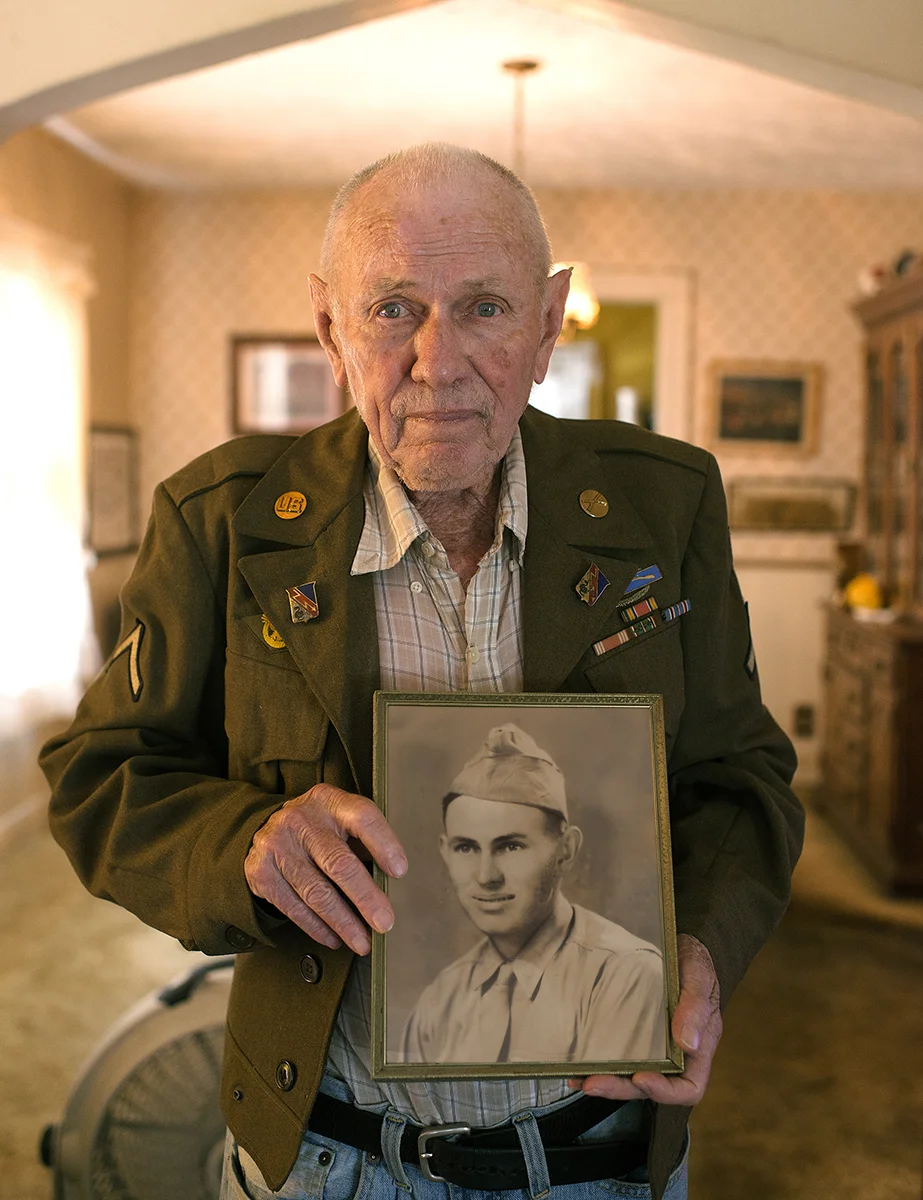

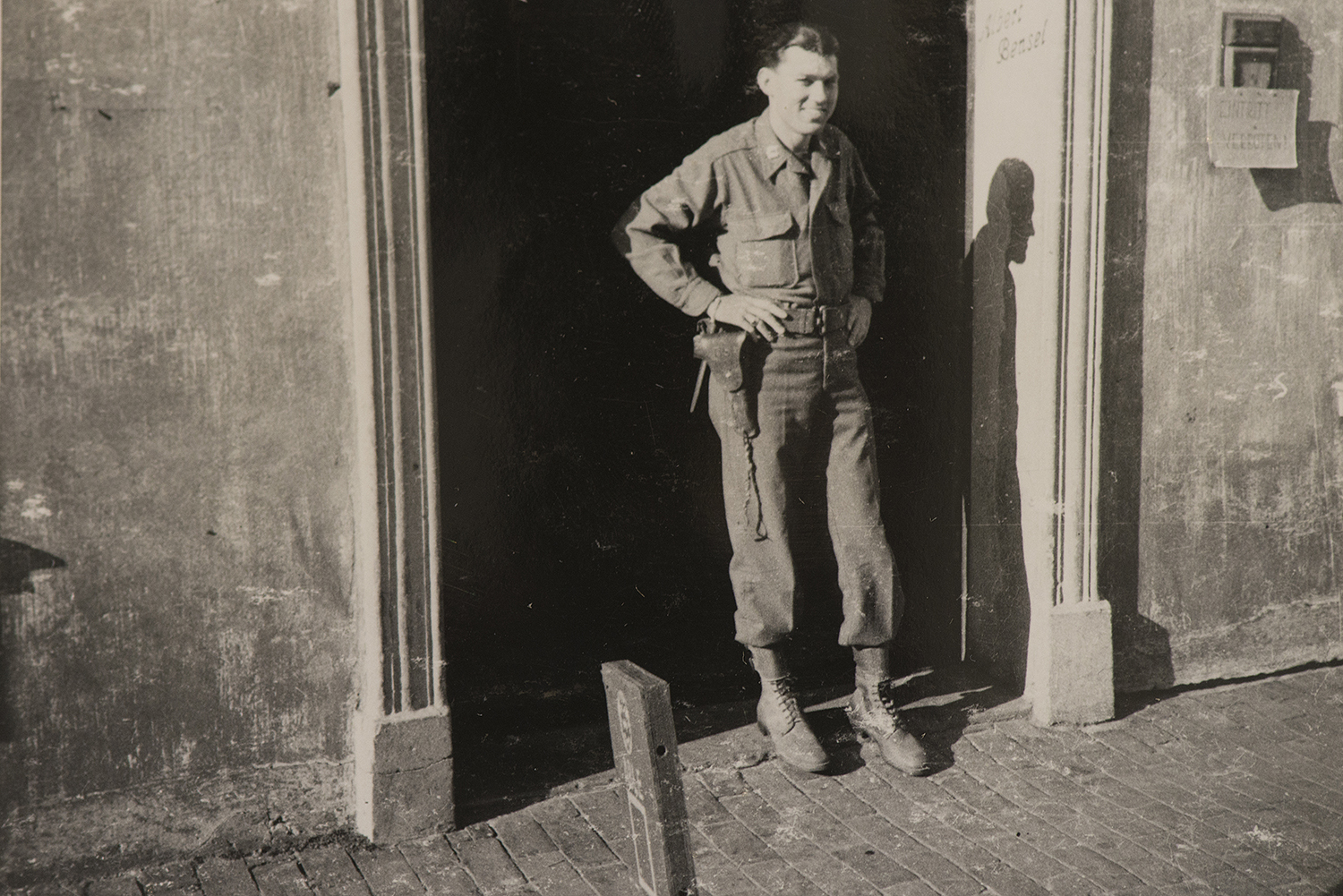

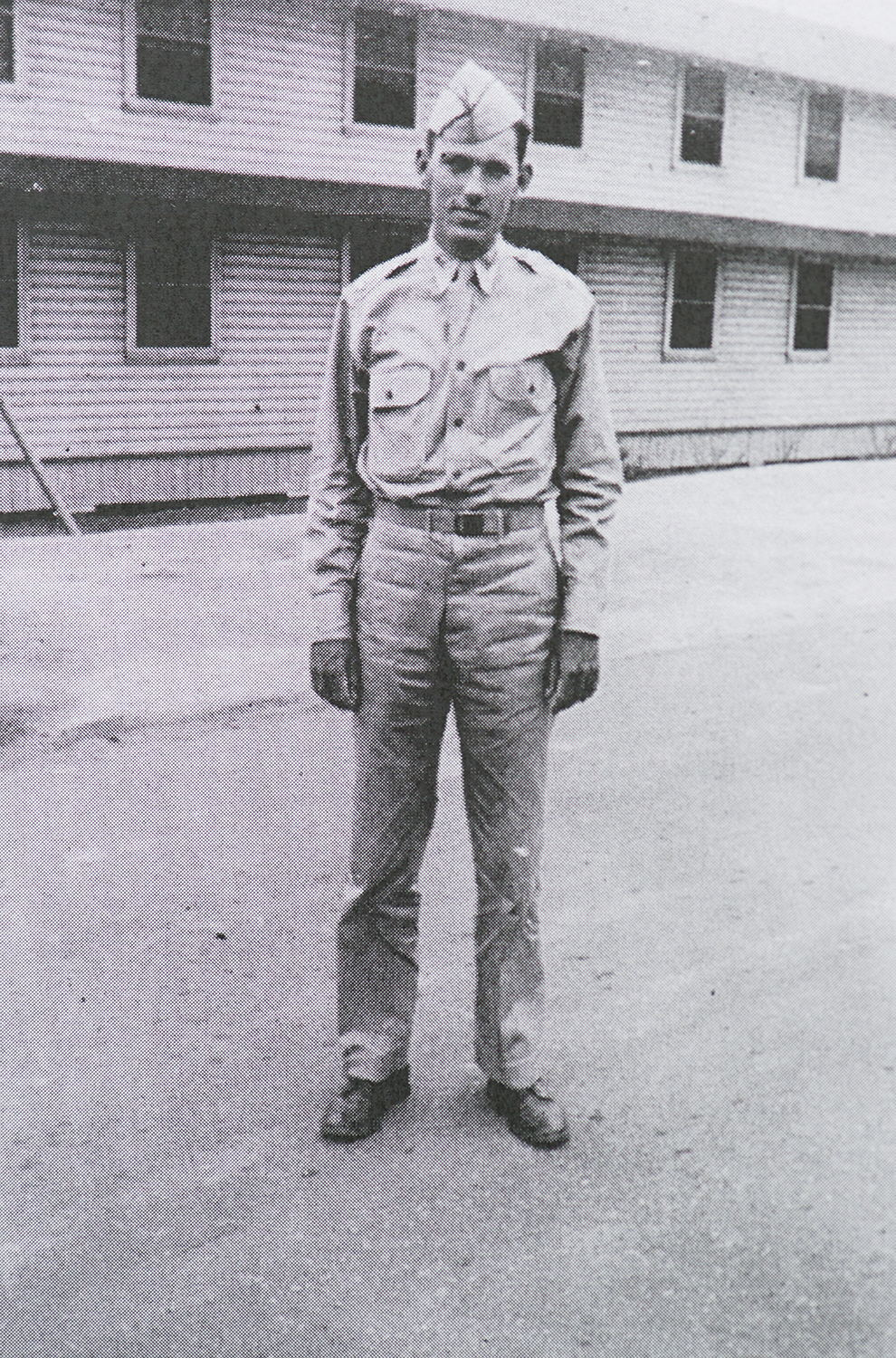

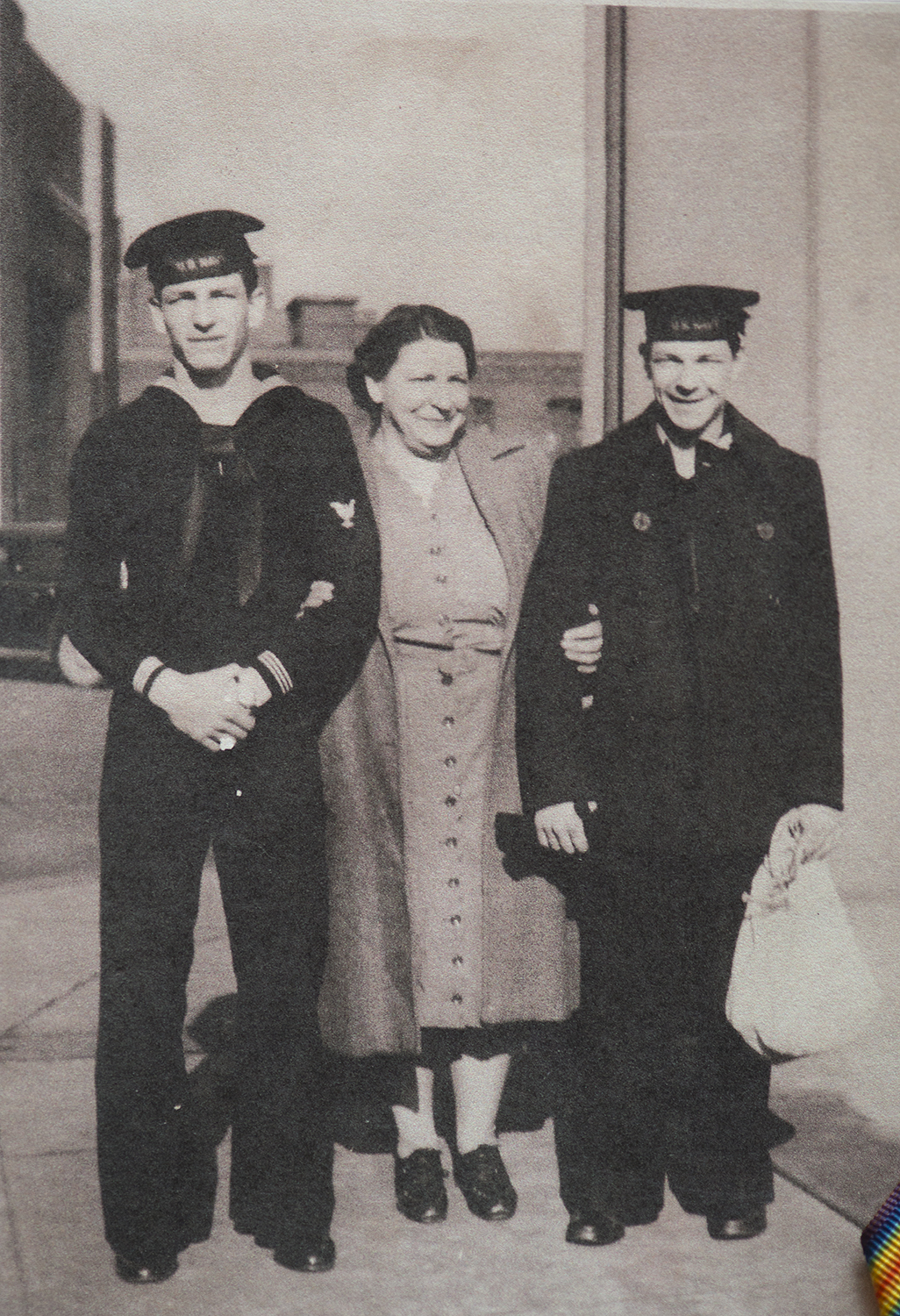

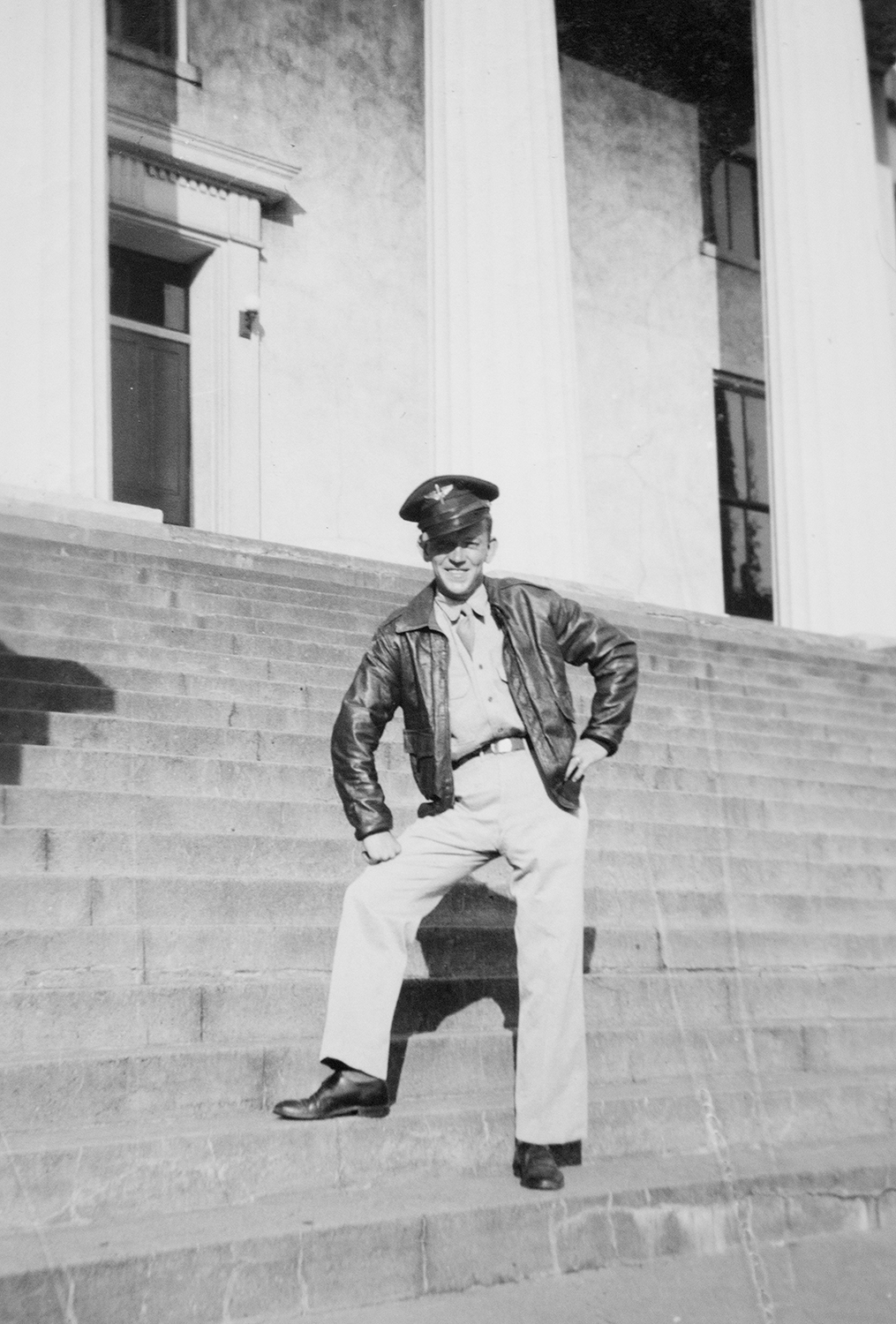

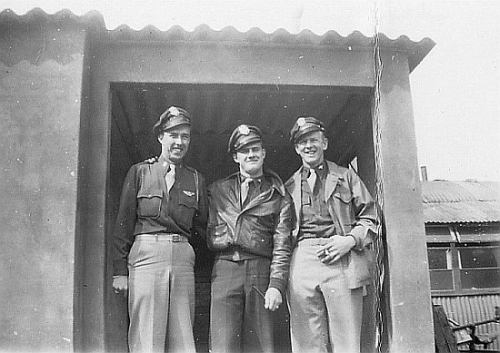

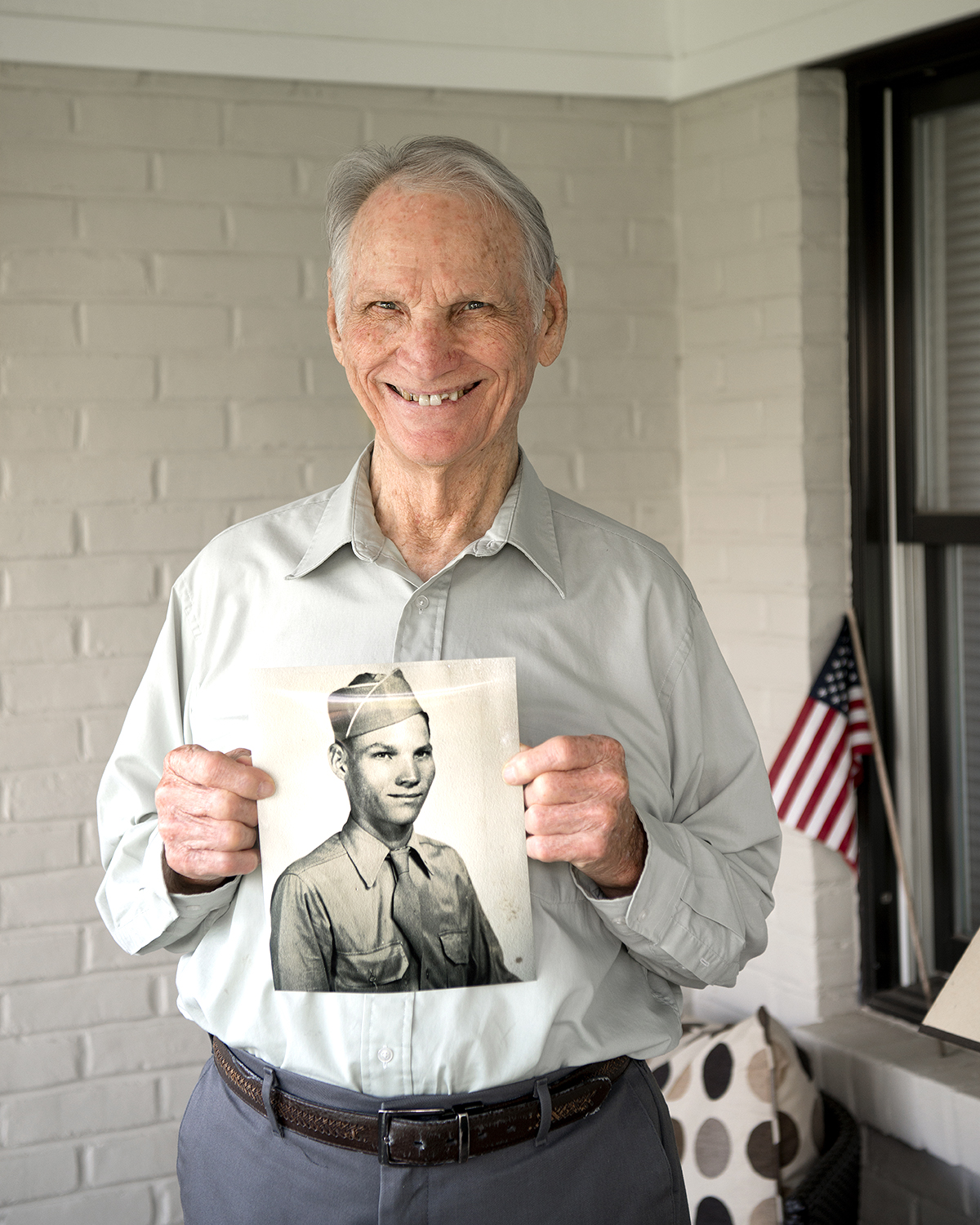

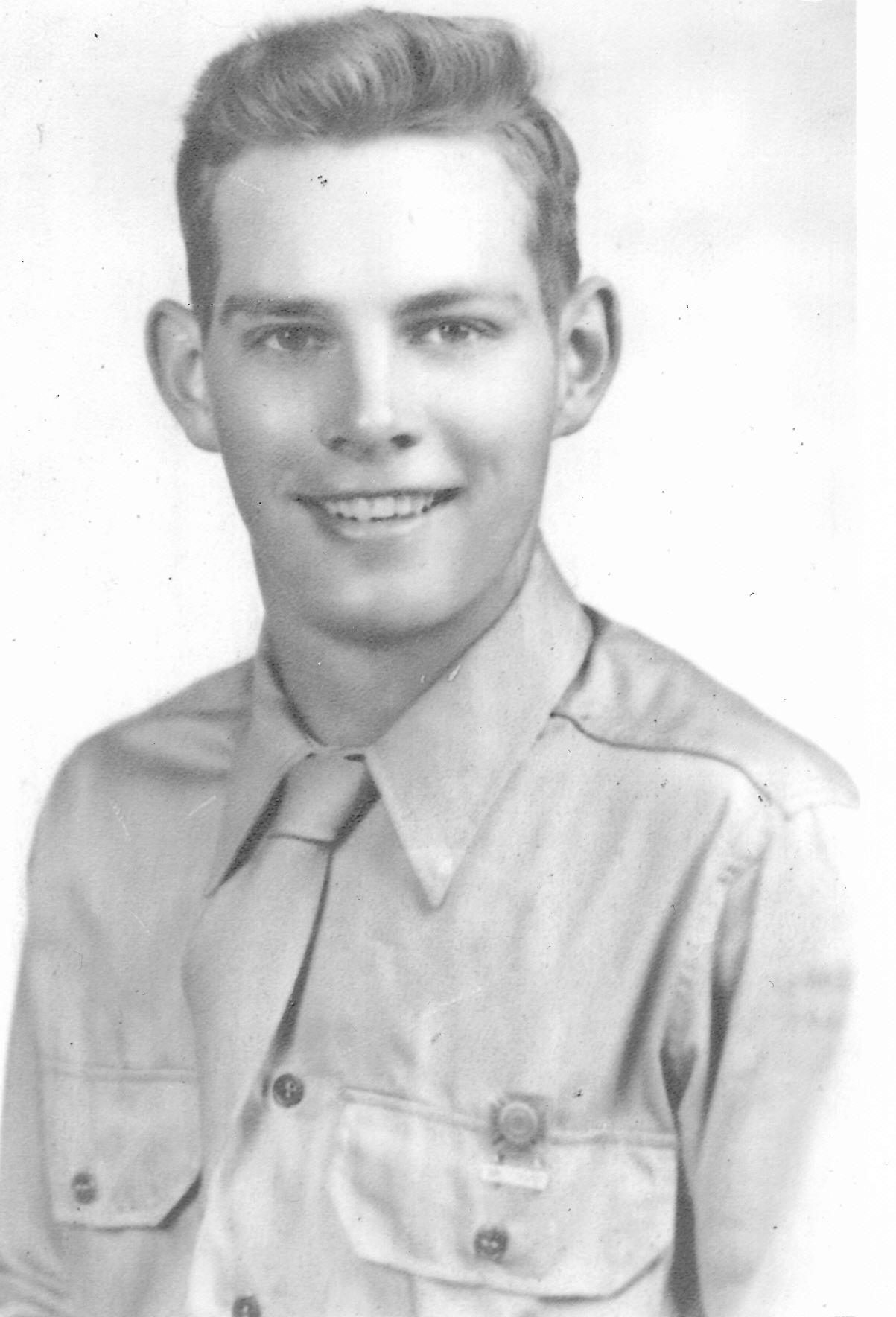

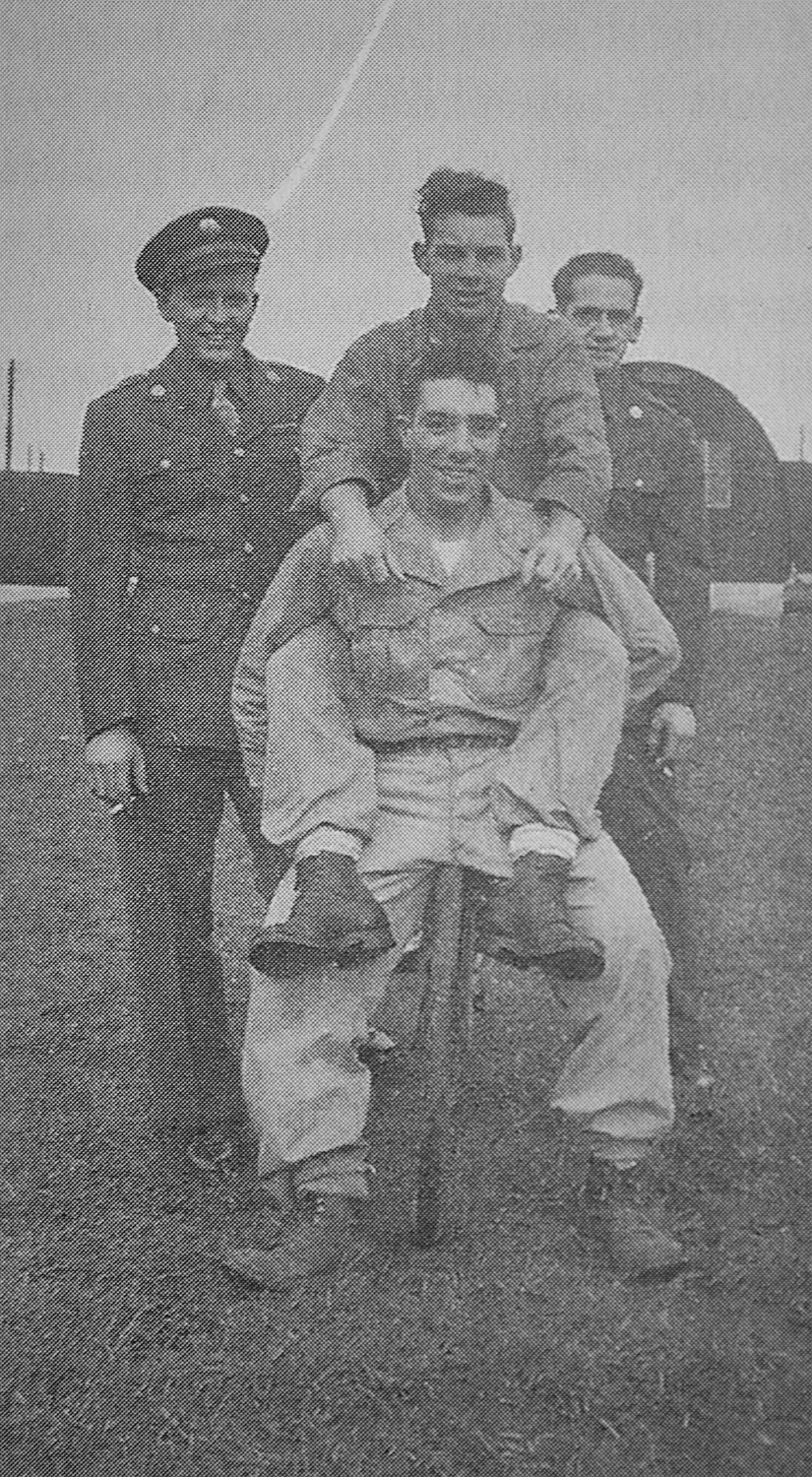

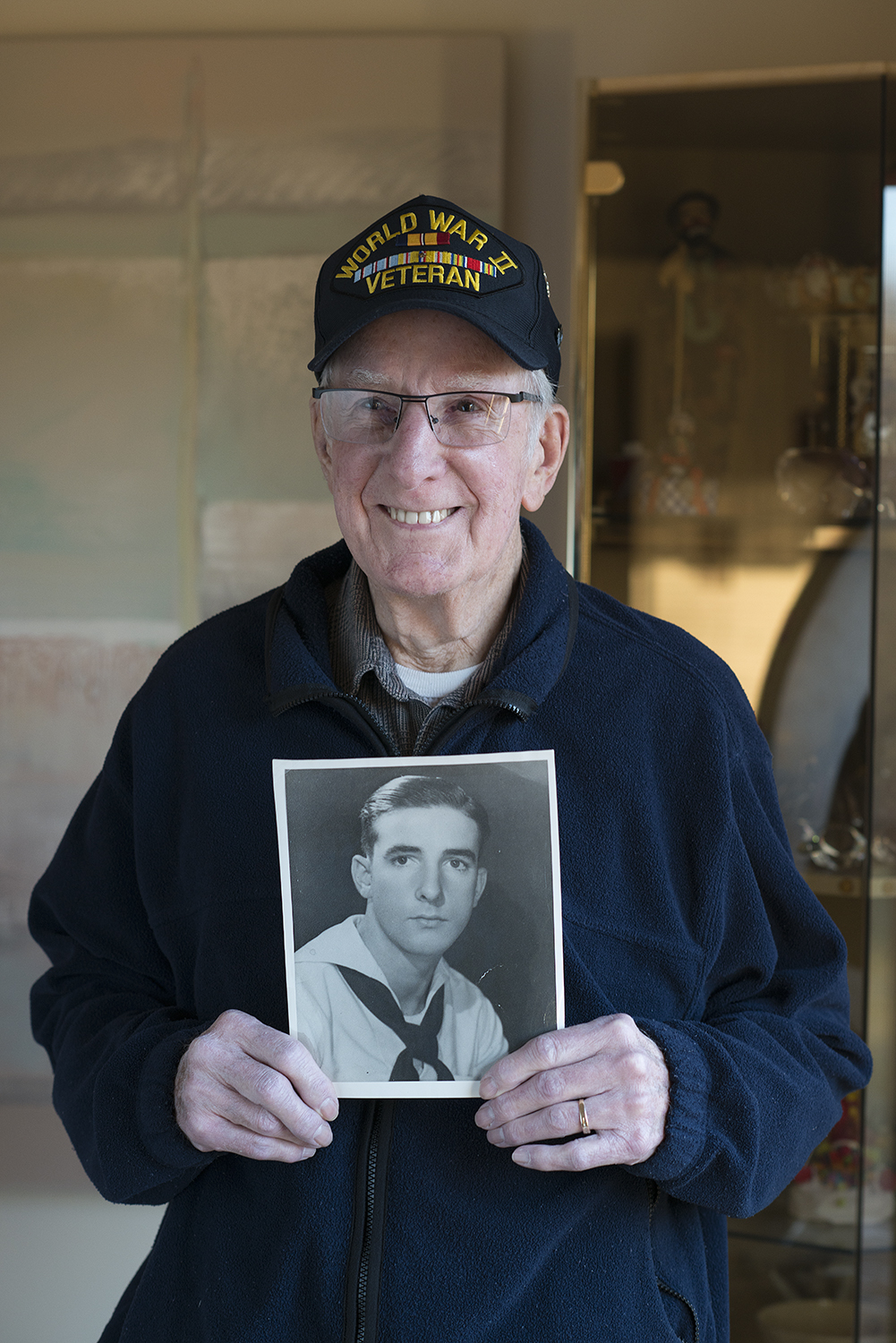

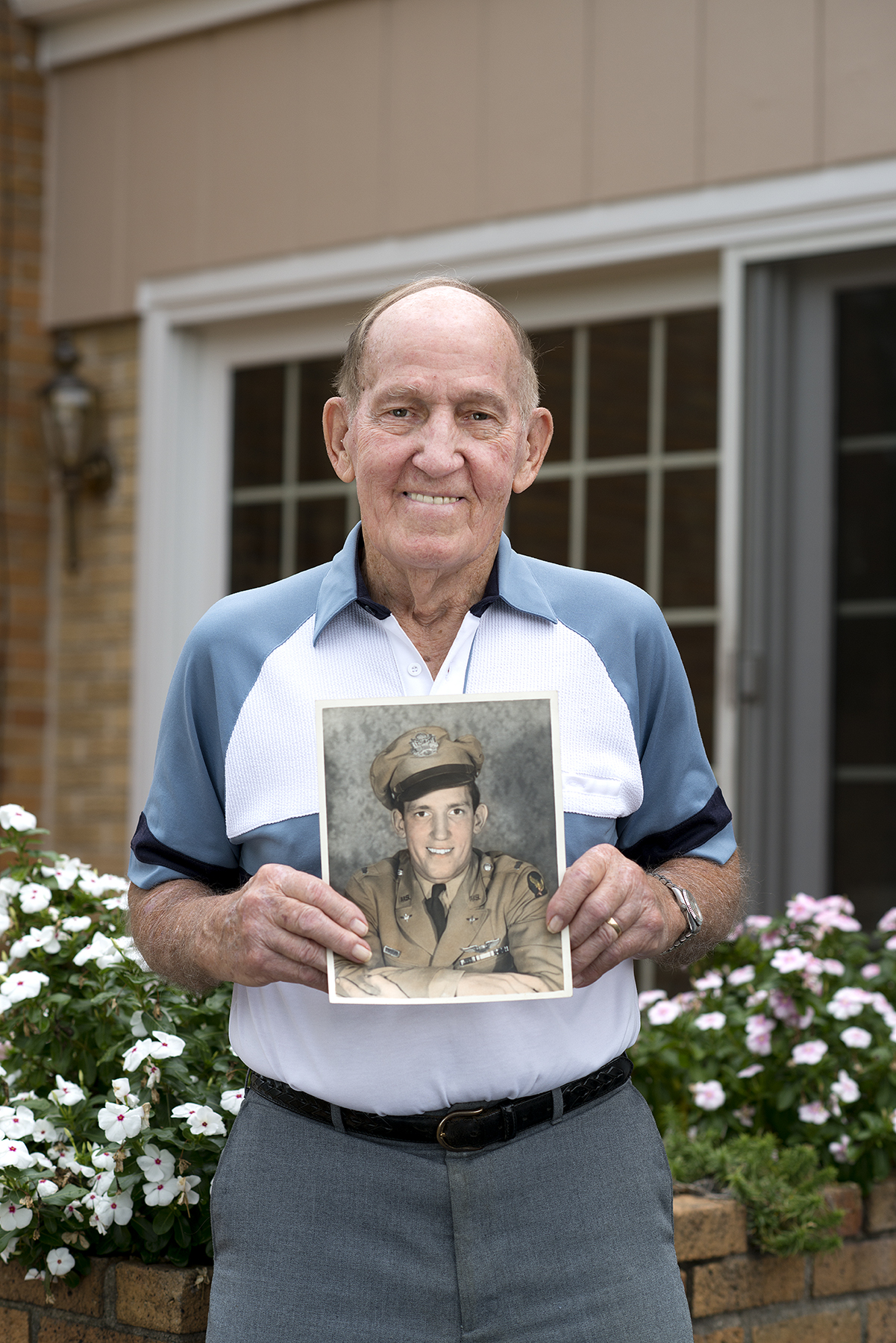

Pictured is Chester in his service jacket sharing the photo of his regiment and talking about the attack on the German pill box. Below those images is his service photograph from 1943.

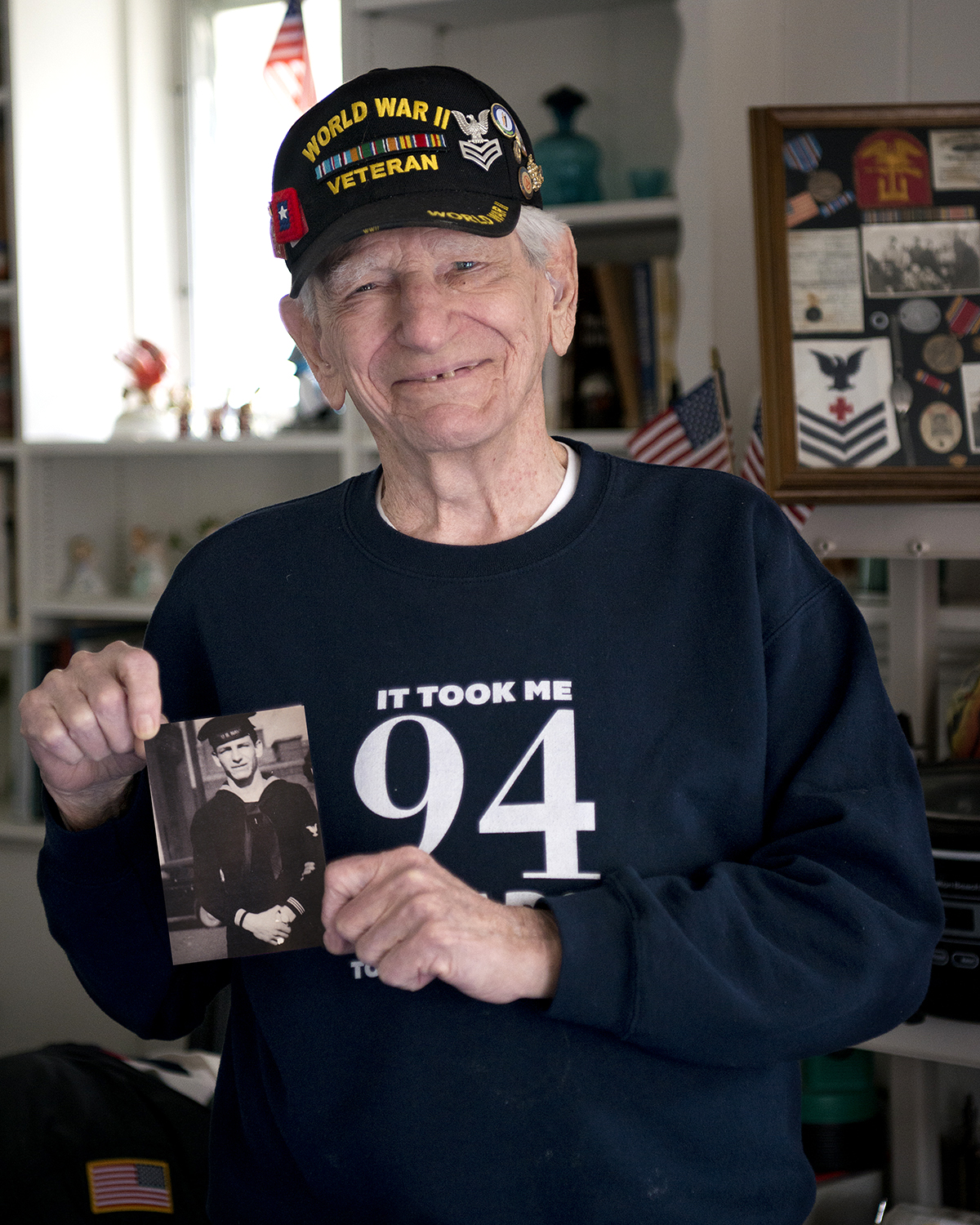

PFC. Chester Bishop on December 22, 2017 at the age of 96.

PFC Chester Bishop in June of 2015 at the age of 94.

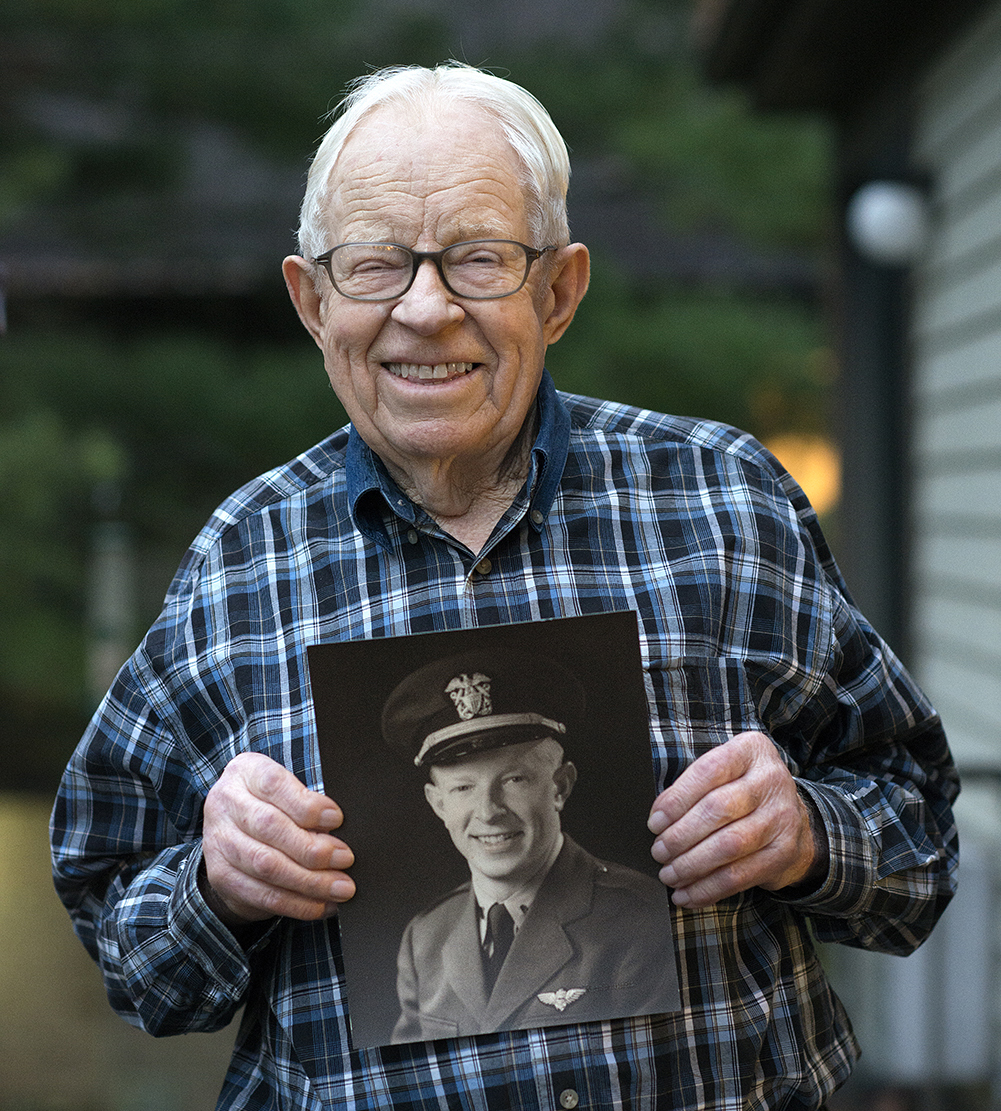

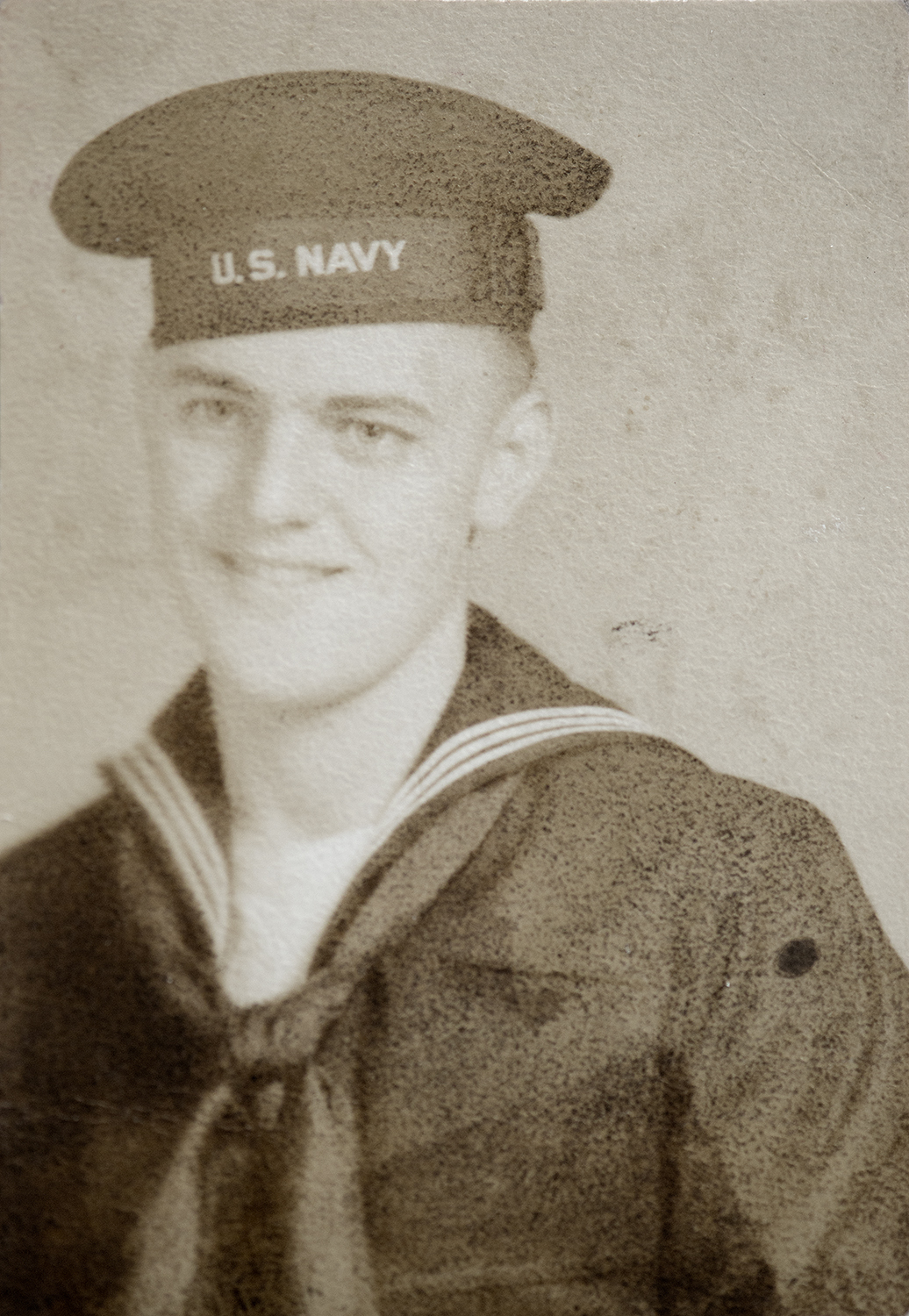

William Singleton

I was born in Brodhead, Kentucky on June 30, 1924. When I was two years old, my parents moved to Camp Dennison, Ohio. My dad worked for the Ohio Railway Company and in 1932 he broke his arm and we had to go on relief. When he was able to do any work, he worked as a farmhand for all of the farms around the Camp Dennison area doing things like cutting corn, gardening and putting up hay. When I was twelve years old, I started going with him doing the same kind of work! Growing up, we would always raise a hog that we would butcher in the fall to serve us through the winter months. We also owned a milk cow and it was my job to milk the cow morning and night. Considering the times, we lived well! Since we were on welfare relief, we were given clothing and we always had a big garden to grow vegetables in and my mom canned everything we grew in the garden. I went through eight years of schooling in Camp Dennison and then I went to Terrace Park High School and spent almost four years there, but walked out during my senior year. When I turned eighteen years old, I got my social security card, got a job at the Terrace Park Country Club golf course and I also worked on farms doing chores in the garden and cutting corn in the fall.

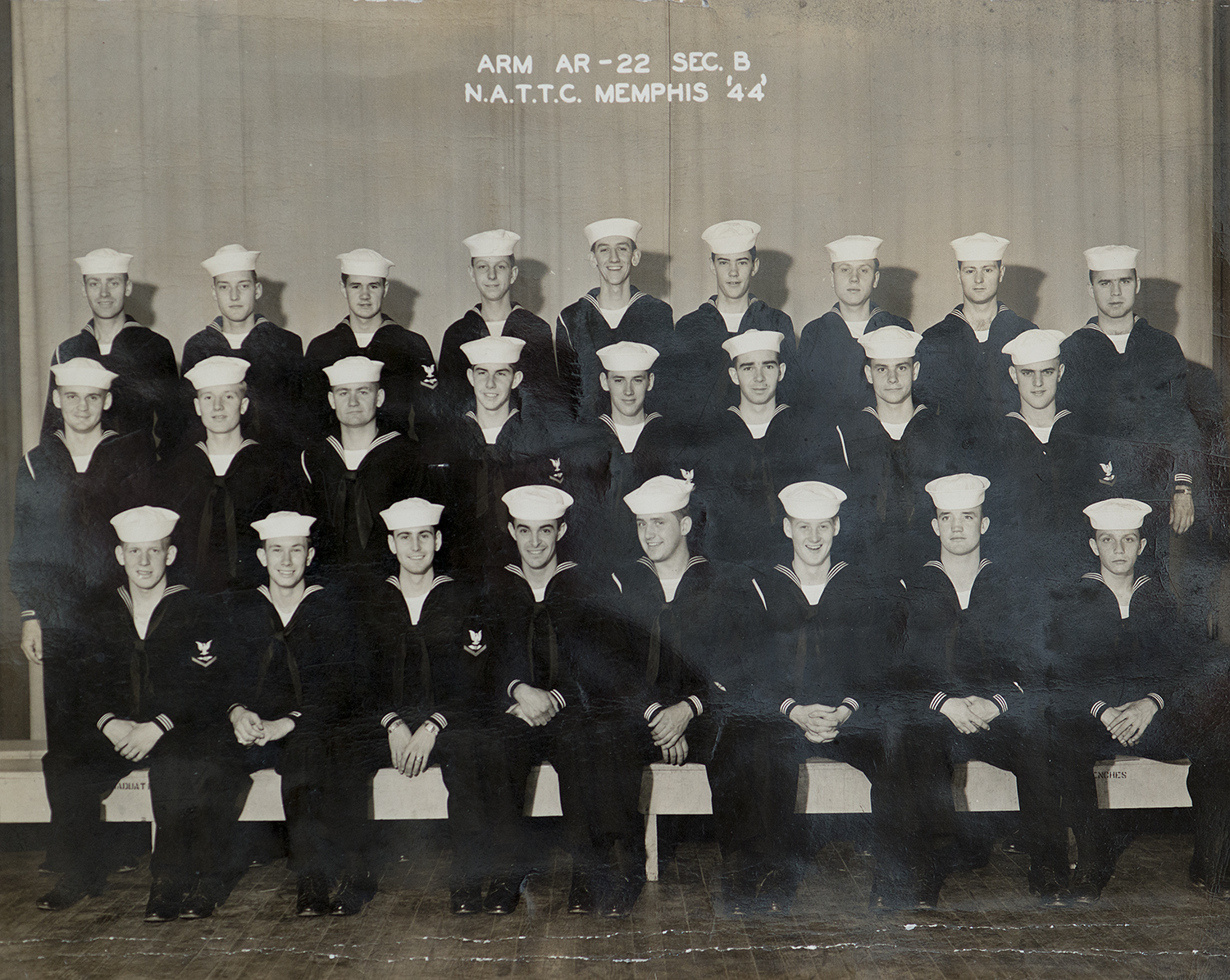

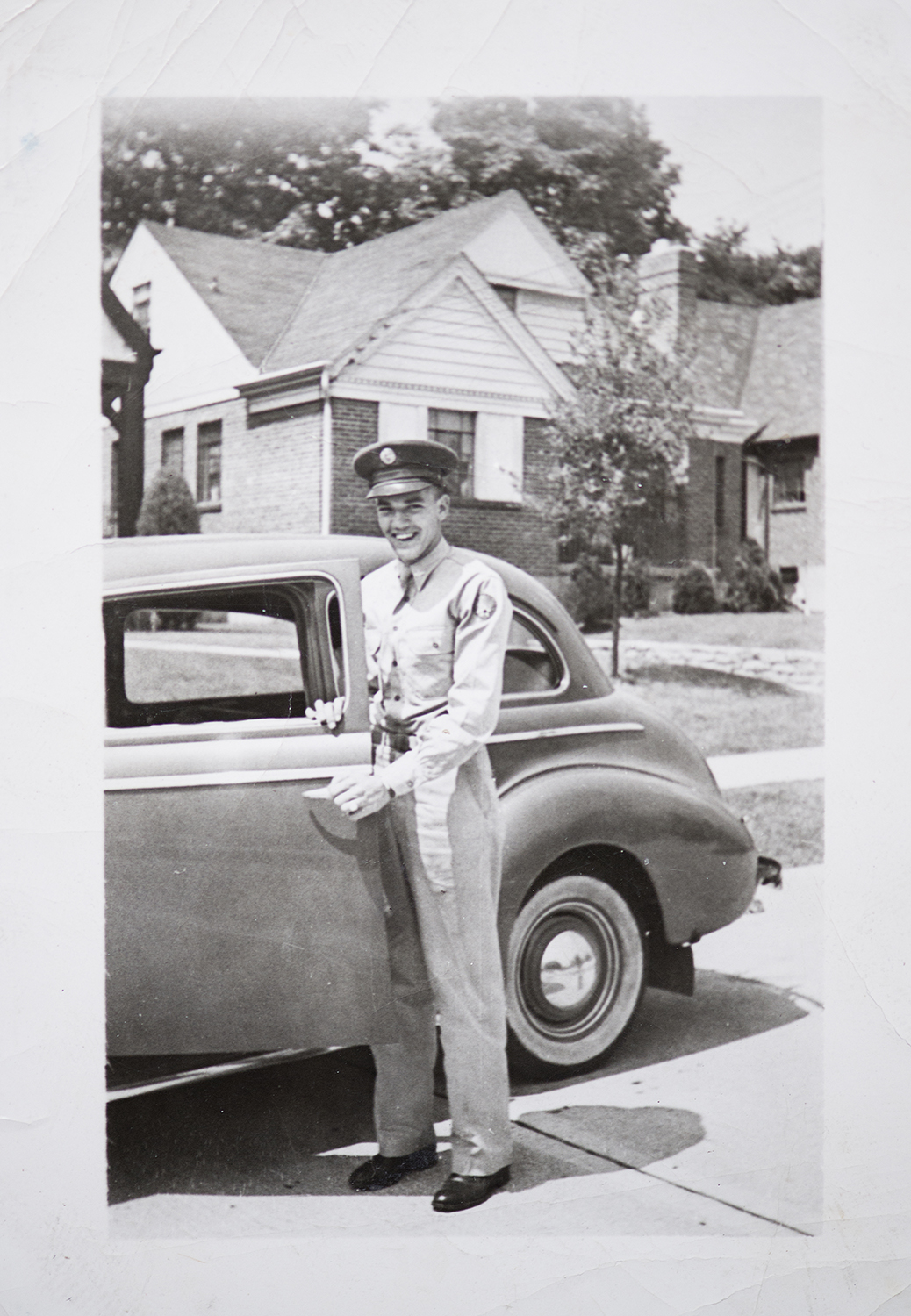

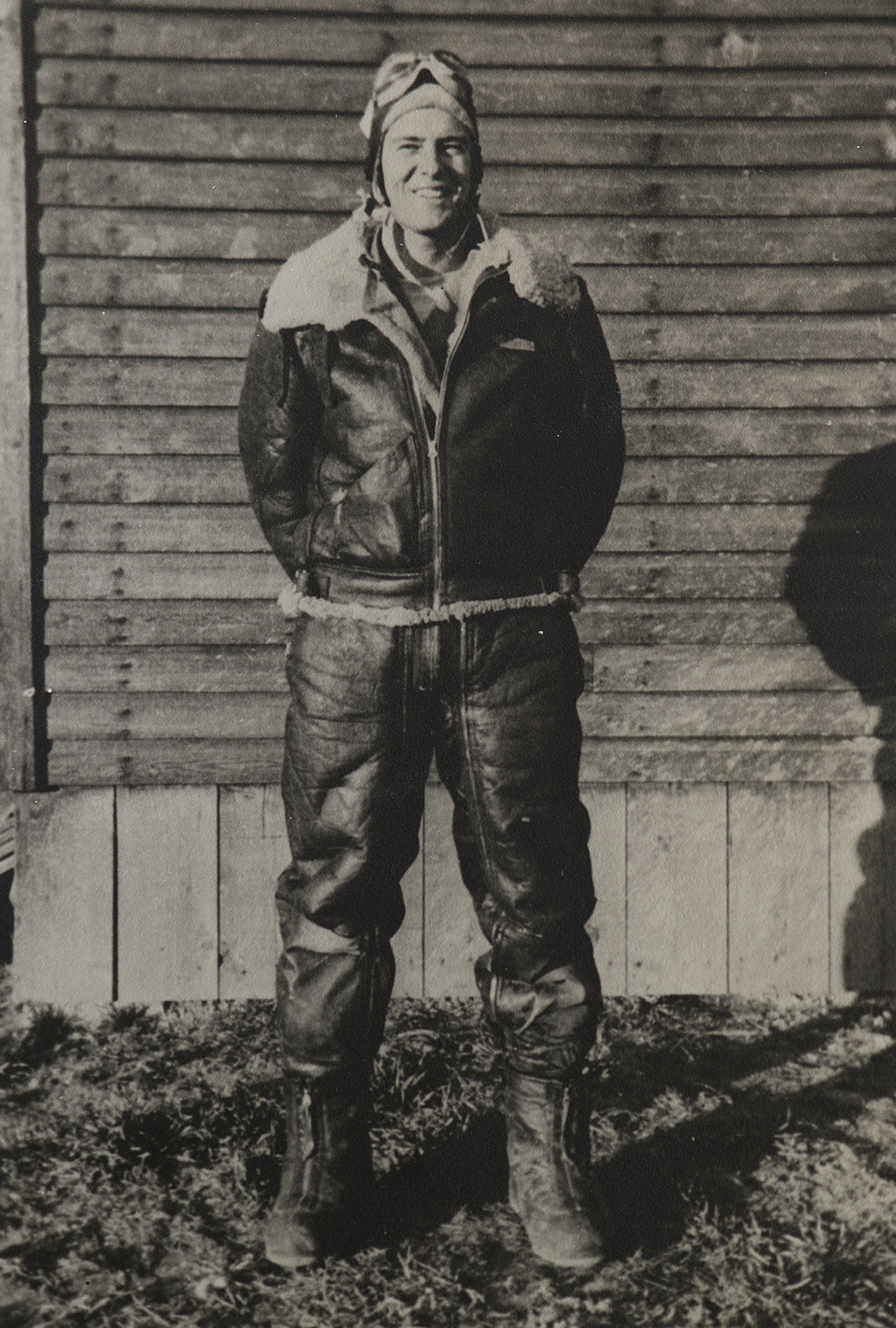

On December 7, 1941, I was working in the pool hall in Milford and I remember the announcement on the radio. I was devastated! I hadn’t even thought about going into the service until another year or so when I heard they were starting to induct nineteen year olds into the service. I thought to myself, I don’t want to be on the ground, but it looks like you get a pretty good life in the Air Force. After I signed up in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, I took the test to get into the Air Force and I passed it! It was really exciting! After I was inducted, they sent me down to Florida right outside of St. Petersburg in the wilderness with palm trees and everything and I thought it was the life. Eight of us lived in a big old tent and did our basic training. After basic, I was sent back to Fort Thomas and I was assigned to Colorado to go to gunnery school. It was beautiful. Our camp was in the back of Pikes Peak, so I got to wake up every morning and look at Pikes Peak! I was trained on the Norden Bombsight as well. Later on during training, I went to another gunnery school in Boulder, Colorado. In gunnery school we learned how to shoot a machine gun! We’d go up in an airplane and shoot at moving targets.

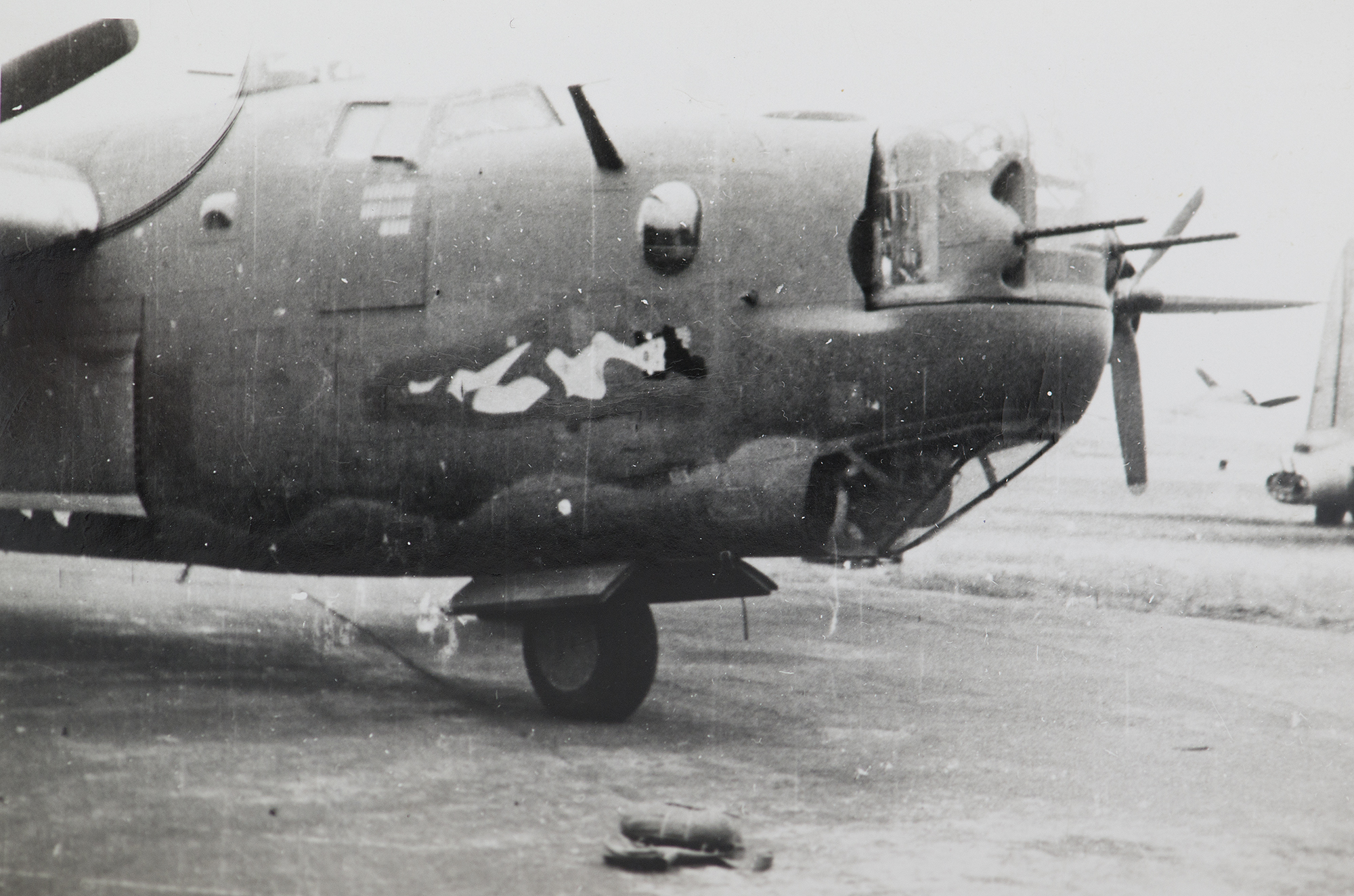

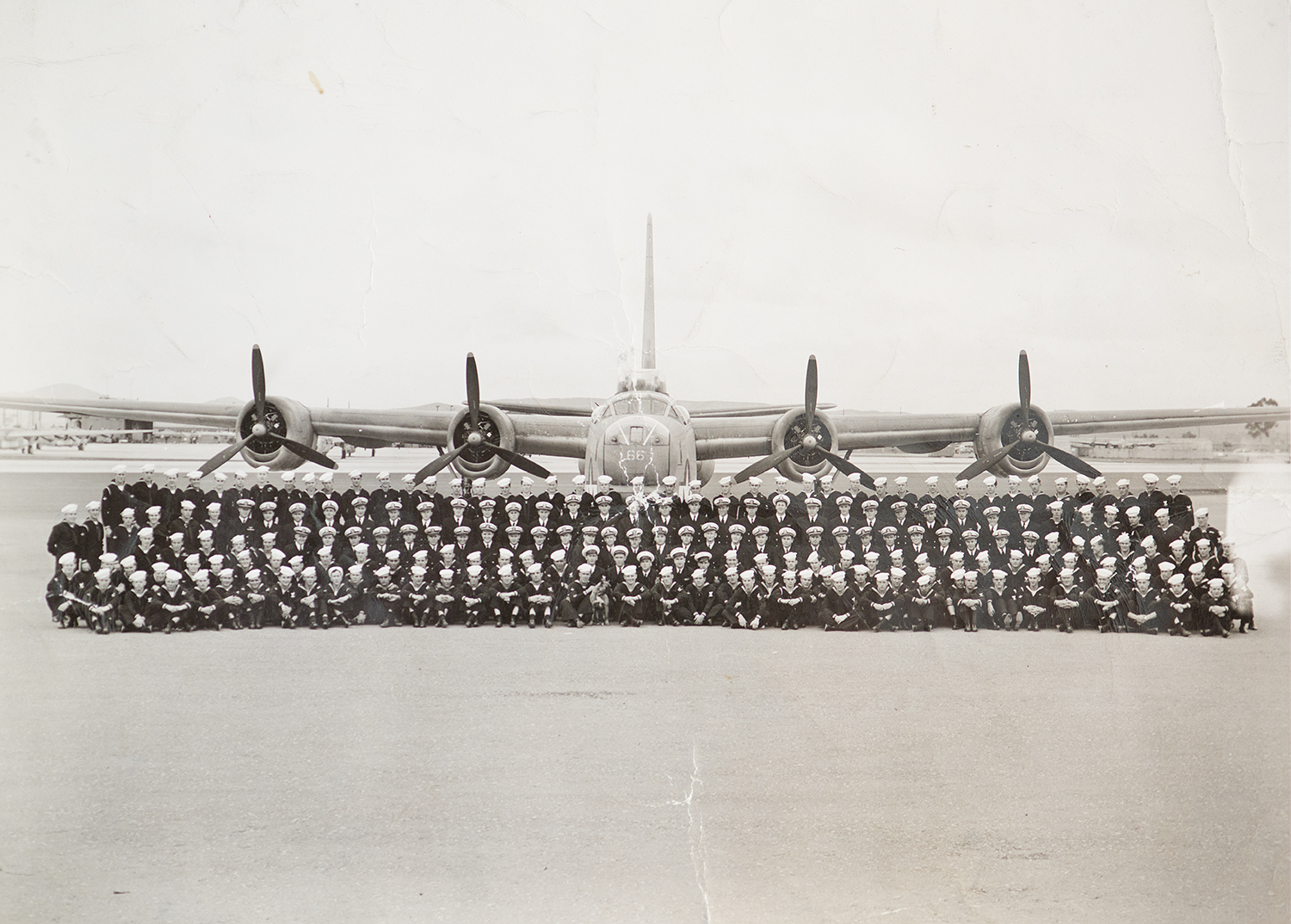

From there, I went to Alamogordo, New Mexico. This is where we formed our 839th Bombardment Squadron of the 487th Bomb Group. I had an interesting experience during training there. We were doing some practice night bombing near El Paso, Texas and on our way back from the bombing mission, one of the booster pumps went out on one of the engines on our B-24 and we crash landed before we made it back to Alamogordo. Our plane came down and hit and spun around, the wings broke off and all of us walked away. It was terrifying! I thought that was the end.

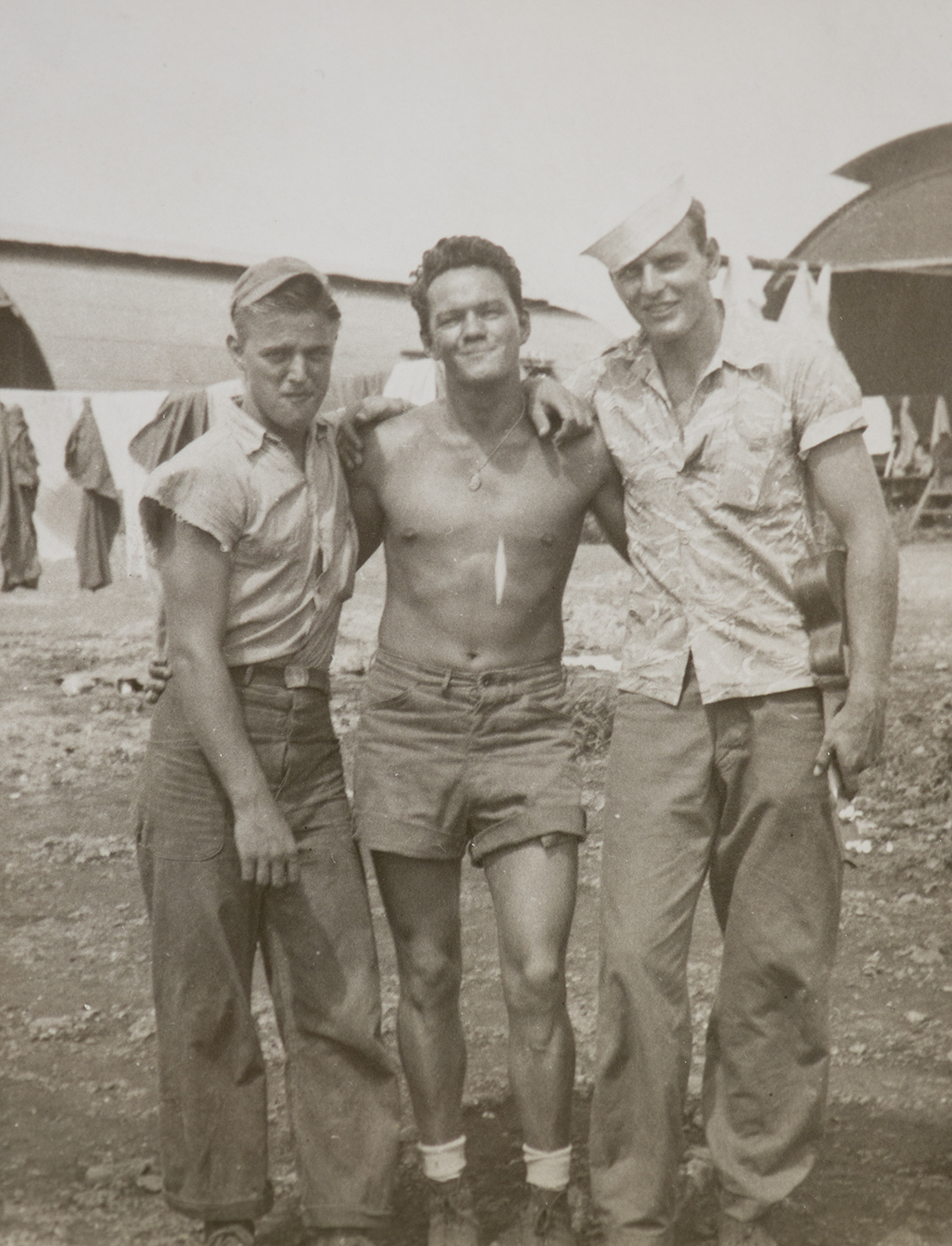

After we trained, we were ready to go overseas. My crew flew our plane over to England and I stayed back with our equipment and went over by boat. Before I shipped out, I spent one night in New York City! I went out to a bar with a few of my buddies and we were in our overcoats. It was one last hurrah before we went overseas. The trip over the Atlantic took about eleven days! We didn’t know whether we were going to be torpedoed or not. Once in England, we were assigned to the Eighth Air Force and stationed at Lavenham Airfield. That’s where I remained stationed for my entire time overseas. I flew sixteen bombing missions in a B-24 and then we switched to B-17s and flew sixteen more missions for a total of thirty two missions. The B-17 was a much better plane to fly in than the 24! Following my thirty second mission, during the interrogation we always had following missions, the officer came up to me and said, “Sergeant Singleton, that was your last mission.” I about fell over! Of course they always had a bottle of booze for us to drink after the bombing missions.

I was the nose gunner and bombardier for our crew. I was up there extended out in front of the plane in a plexiglass bubble. Once we got up to ten thousand feet, we’d turn our oxygen on and get in position and stay there until we got over the target. That’s when I’d start saying a good prayer to the Lord. During the missions before and after we hit the target, there were always German fighters coming in attacking us and I would return fire, but I don’t think I ever hit any. I got to see other planes get shot down and every time I would thank God that it wasn’t me. It’s a very scary position to be in, let me tell you. I just thank the good Lord that I’m still here.

Before missions, I was always the last member of my crew to get on the plane. I didn’t like seeing the engines warm up while they were filling the tanks with 100 octane gas because it would run over the wings and I thought to myself, one of these days it could catch fire! Once all of that was finished and all four engines were started, I’d climb up through the bombay doors and then down underneath the pilot and co-pilot into my position in the front nose of the plane.

Our first mission was up to Belgium to bomb railroad yards. They were really well protected. You could tell the difference between an 88 and a 105 shell when it burst too. The 88s can get up a little faster and the 105s came up a little slower, but packed a bigger punch! You could easily tell what it was by the burst and the flame when it exploded.

On June 6, 1944 I flew two missions. At this time, we were still in the B-24. During the first mission, we flew over the channel before the landings began and hit the coast line defenses with our bombs to help soften the German defenses. The channel was just loaded with ships as far as I could see up and down. Our plane was only at about five thousand feet off of the water, so I had a really nice view of the boys down below. Then we hit the coast with the first wave of bombs through which our ground forces would push through. Then we returned to England, refueled and loaded more bombs. On our second mission we flew further inland and dropped bombs onto the railroad stations so the Germans couldn’t rush reinforcement troops up to help with the defense of the beachhead.

Crash landing the B-24 in the U.S. during training was as close as I came to losing my life during the war, though I saw a lot of planes shot down around us while on the thirty two missions. We were just one of the lucky ones because when that anti-aircraft comes up it just spreads all over and you don’t know which plane is going to get hit. Every single mission there was flak galore.

On my trip home, I sailed back across the Atlantic and we anchored in New York Harbor. I was discharged at Sheppard Field Texas. I flew from there back into Cincinnati and arrived at Lunken Airport. It was so wonderful to come home to Milford. Naturally I had to find a job. I worked for a guy at a grocery and I was a butcher. Before I left for the war at age 19, I was learning how to be a butcher. The owner, whom I knew, was glad to see me back home because he said he needed a vacation. I worked for him for two weeks while he vacationed. At the same time, there was another guy who owned another grocery store in Milford and offered me $100 a week to come work for him! Back in those days, $40 a week was the going salary, and he said I’d be the butcher and manager of the store. I said absolutely! The owner had an alcohol problem though and I didn’t want it to ruin my name, so I quit after six months because I didn’t want my name to be ruined. In the meantime I had become friends with the man who was delivering the produce at that time and he had two trucks. I talked to the owner and he offered $40 a week and I said okay, but let’s work on a percentage basis past a certain amount. He agreed. I worked for him for nineteen years and then I bought him out. At that time I had five trucks running out through the country and I had ten people working for me. I had a really good business and I was able to retire at fifty seven years old. Since then, I’ve been dabbling in real estate.

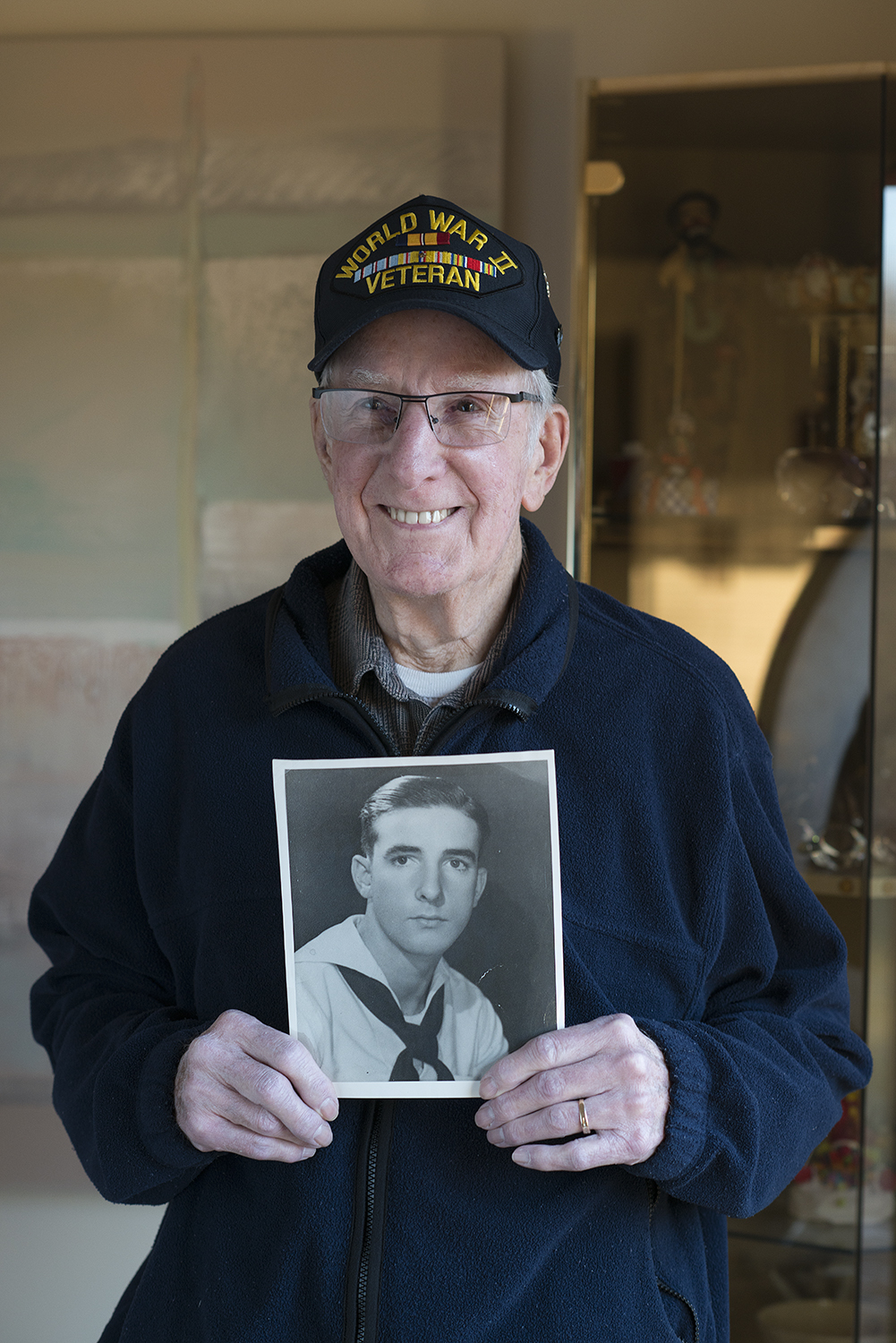

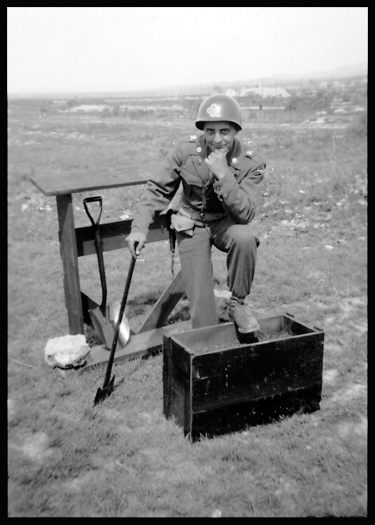

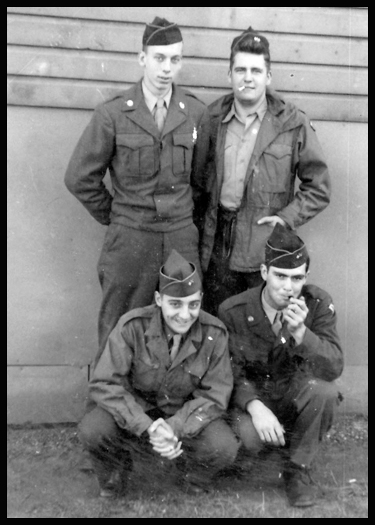

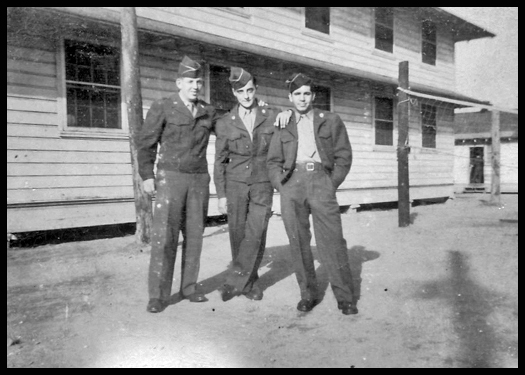

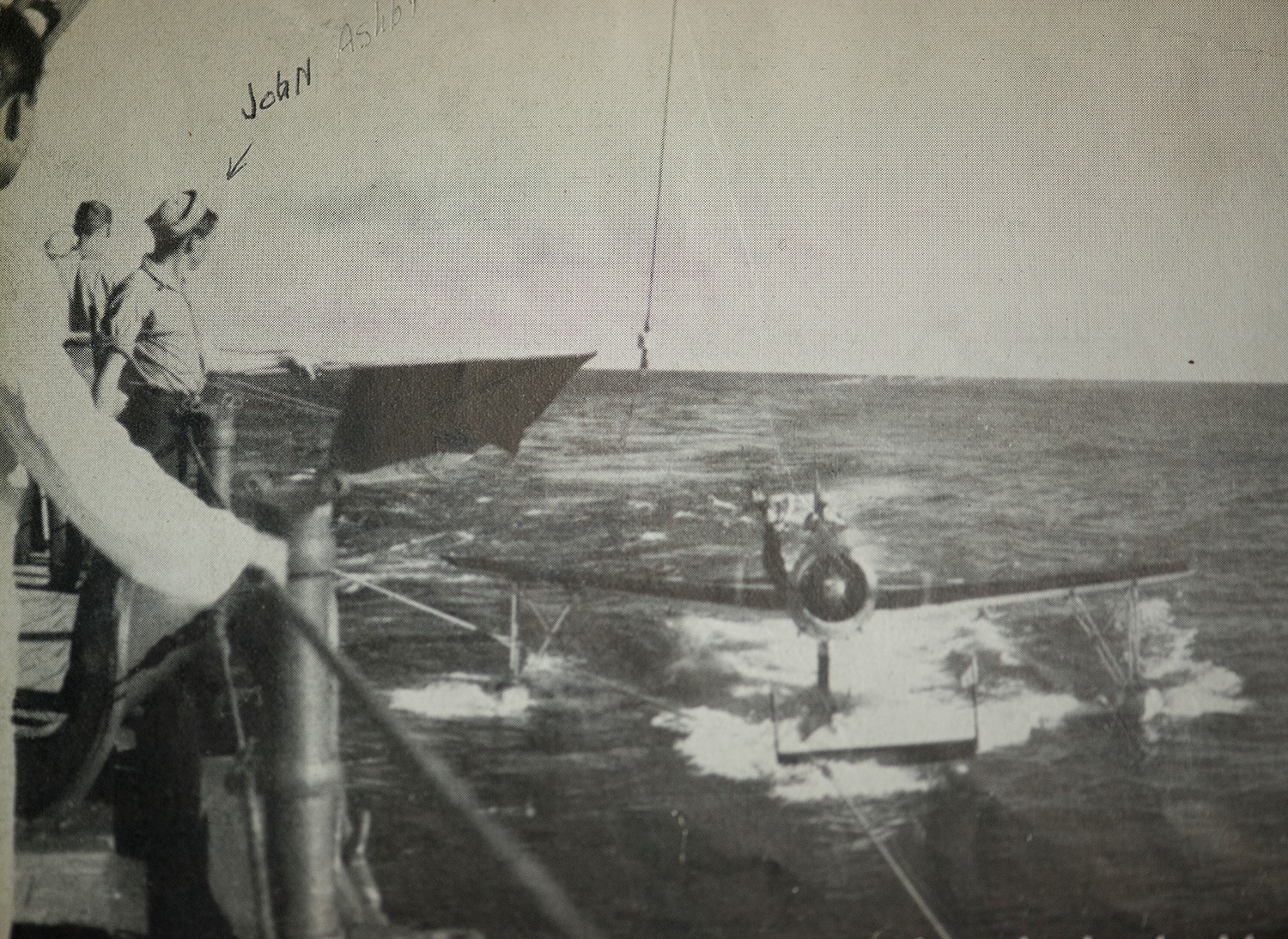

John Sansalone

My name is John R. Sansalone and I was born in Watson, West Virginia January 21, 1929. My family lived in a coal mining community and it was a very poor area, but we didn’t know we were poor because we had the hills and the mountains around us, we could play in the three rivers that ran through the town and most of the people were employed by the coal mines. Most who lived in the town were Italian immigrants and some were Russian and Polish immigrants. My grandfather came over first prior to World War One and had to return to Italy to serve in the military and then came back to the U.S. and worked for three years and then brought my grandmother over, my mother at age nine and an uncle who was a lot younger. They settled in Watson. My father was a coal miner, but he didn’t like it so he started a small grocery store, which is where he worked until the day he died. My grandfather was a stone mason when he came over from Italy and then became a coal miner. All of my uncles were also coal miners until the war broke out and then they went into the service. Everybody had their own garden where they could harvest fruits and vegetables and can them and some of our neighbors raised hogs or chickens. We had chickens to help overcome the food shortages caused by the depression. That is how we supplemented the food on our table. Watson was a beautiful part of the country, it was really lovely.

On December 7, 1941, I was at a movie with a friend of mine who was a newspaper boy. They stopped the movie and told us all to go to the newspaper office, which was right across the street from the theater. I can still see the big headline about the war being declared. At that time, I was still pretty young, so I don’t remember being frightened, but I do remember subsequently to that, talking to my mother and saying, I hope the war lasts long enough so I can go into the Army! She almost hit me over the head, you know, she was a very gentle woman and said I didn’t know what I was talking about. But that day is really etched into my mind. I remember it very well.

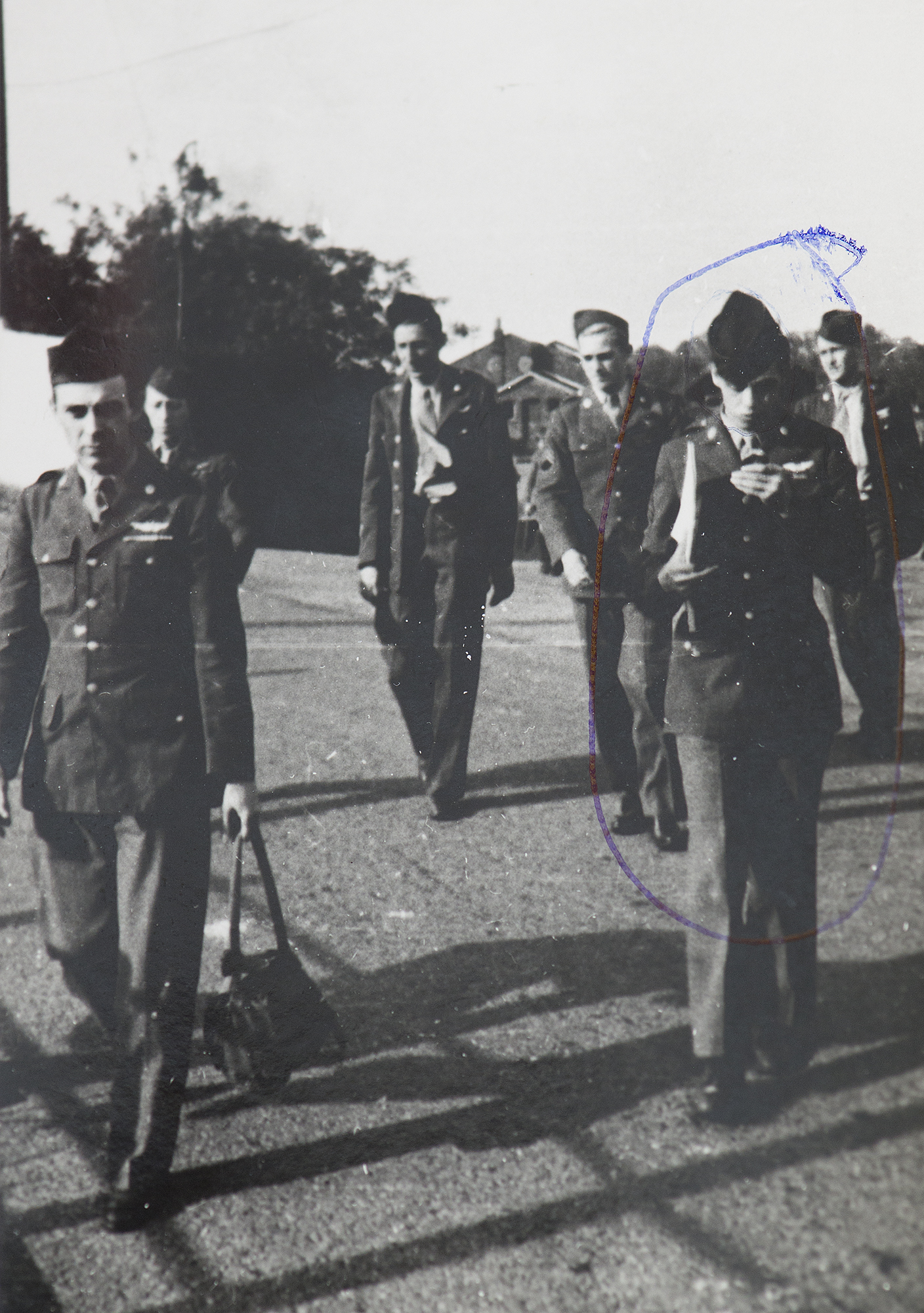

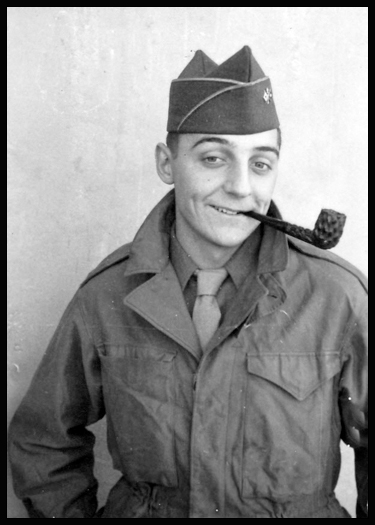

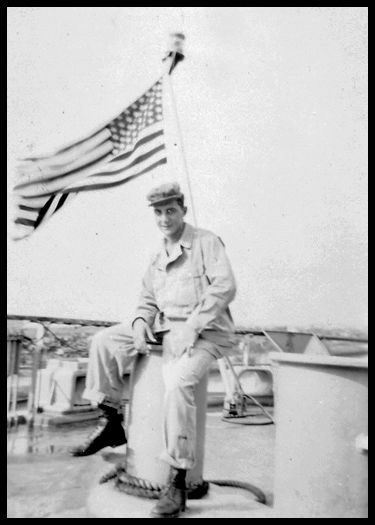

In 1946, I graduated high school and that is when I volunteered for the Army. I was just 17 years old. I had started school early because of my birthday and I had to talk my father into signing the papers to allow me to go into the service. Of course he didn’t want to do that, but I convinced him that if I did go, I could get the G.I. Bill and then I could go on to college. That helped change his mind. After being called up I was sent to Indiana for induction and then to New Jersey for basic training and within six to eight weeks, I was overseas in Italy in the occupation troops with the 88th Infantry Division. During the trip over, we were on a Liberty Ship and many of the men got sea sick, but I did not. We were stacked up on bunks five or six high down in the hold. I never went down there, I just stayed in a life boat up on deck all the way over. I was able to enjoy fresh air up top instead of the bad air below deck. We landed in Italy on Christmas Eve, 1946. For a young guy that was a little hard to take. There weren’t any celebrations going on though.

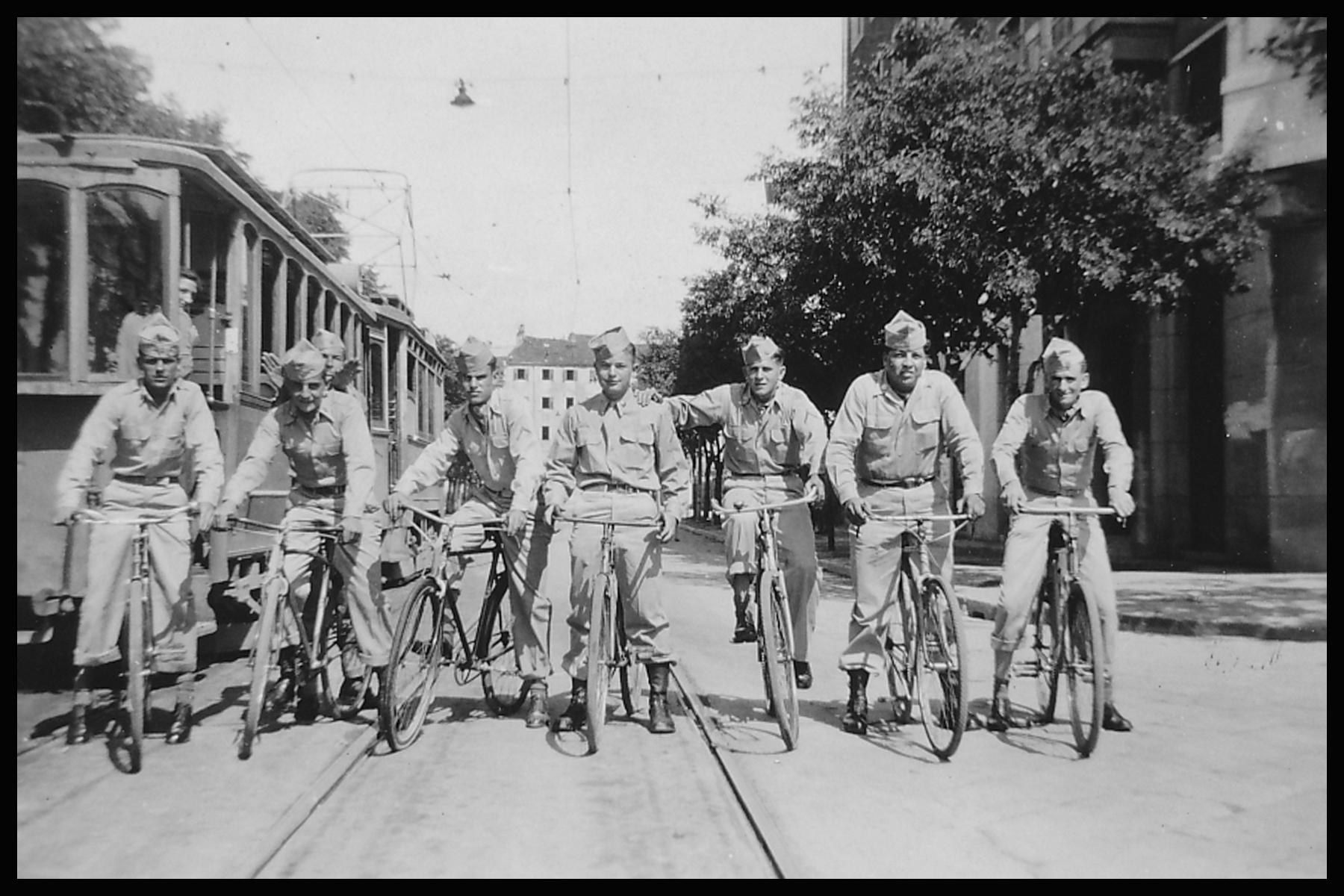

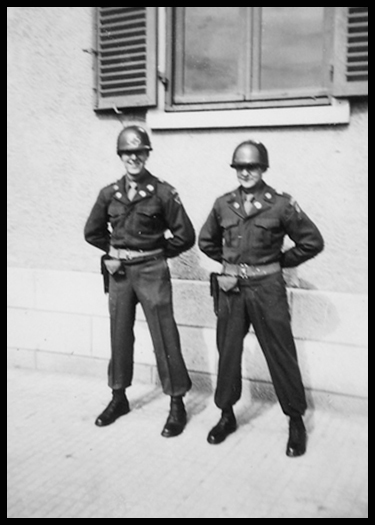

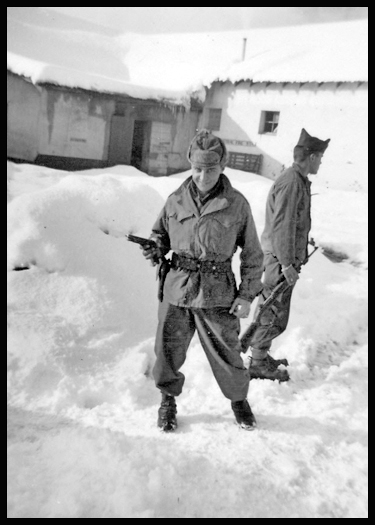

Although I was only 17 years old, I made squad leader and I was the gunner on a mortar squad. We were sent up to northern Italy to a small town on the border called Tarvisio. The U.S. and the British were there occupying that area. The fight between Tito and Mihailovich was going on at that time in Yugoslavia, which was another reason we were right there on the border. For the majority of my time in occupation, we were stationed up in Trieste up on top of a mountain and the city was down below at the harbor. I recall one Easter while I was over there, there was a tram that ran a cable car from the top of the mountain down to the city and it was very windy there in the spring time and they called that wind the Bora. We would have to cable our quonset huts so they wouldn’t get blown off. We had to be careful on the border and we actually had some troops that strayed over to the other side and ended up getting captured. Eventually they were released. A lot of the time were were just on maneuvers, on alert and patrol duty and things like that. When we would go on patrol, we would go by foot and by jeep. The jeeps had machine guns and we had side arms. There was a large ammo dump close to where we were stationed that we had to guard and patrol. There were never any instances of people trying to steal anything, but that’s because we were there guarding it.

This was a hot area because the communists were very active. On May Day they came out in force so we had to be on our guard. There were instances where our force would get into arguments with the communists and sympathizers, but nothing serious ever came from those confrontations except exchange of words. Many of the Italians in that area at that time were leaning toward the communists and trying to form some kind of government. From that standpoint is was a touchy situation.

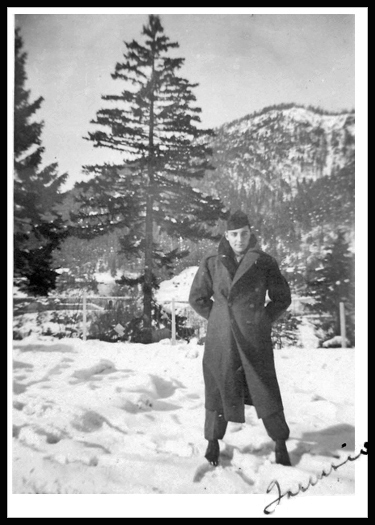

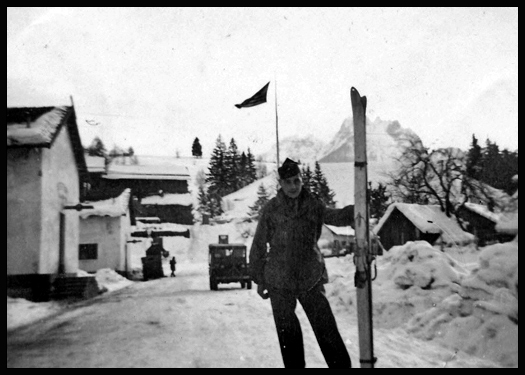

Interestingly, I volunteered for the ski troops. I had never before been on skis and I haven’t been on them since. We mostly snow shoed and hiked to patrol the mountains in the snow. I was the gunner on the mortars. I directed the fire when we fired our rounds.

One specific thing that stands out in my mind, was that the war had just ended and people were still suffering, they didn’t have enough food. At the end of all of our meals, the locals would be lined up at the chow line to take the remains on our plates to take home and eat.

Later on I was able to go to Venice for three days for a golf tournament because I had gotten to know the Lieutenant. When I was younger, I was a golf caddy and learned to play the game.

I was stationed in Italy a little less than 18 months and then we returned home by way of troop ship. It took a few weeks to cross the Atlantic. When I came back stateside, I was sent to Fort Knox where I was eventually discharged. This was the end of my experience in the Army.

Within five or six months, I was enrolled in classes at the University of Cincinnati. What it did for me, being in the Army at that time, was save me from having to go to Korea and Vietnam. Luckily I had already spent my time in the service so I wasn’t called up. Otherwise I would have been involved in Korea and probably Vietnam. At the University of Cincinnati, I studied engineering, which was a five year course. I was on the G.I. Bill, so all of my friends and 80% of the students were G.I.’s. I lived in a barracks and eventually became the “dorm mother” of the barracks. After the first year at U.C., you could work for six weeks and go to school for six weeks. That supplemented the income that I needed to finish my schooling and thats the reason it took me five years to finish. Using the G.I. bill transformed my life, from what would have otherwise been lived out in a small coal mining town in West Virginia as a coal miner to living in Cincinnati and becoming an engineer. My experience defined a real sense of service and purpose to my country. Eventually my company grew to the largest engineering company in Cincinnati and through the course of my career we developed over 500 developments and I still come to work seven days a week.

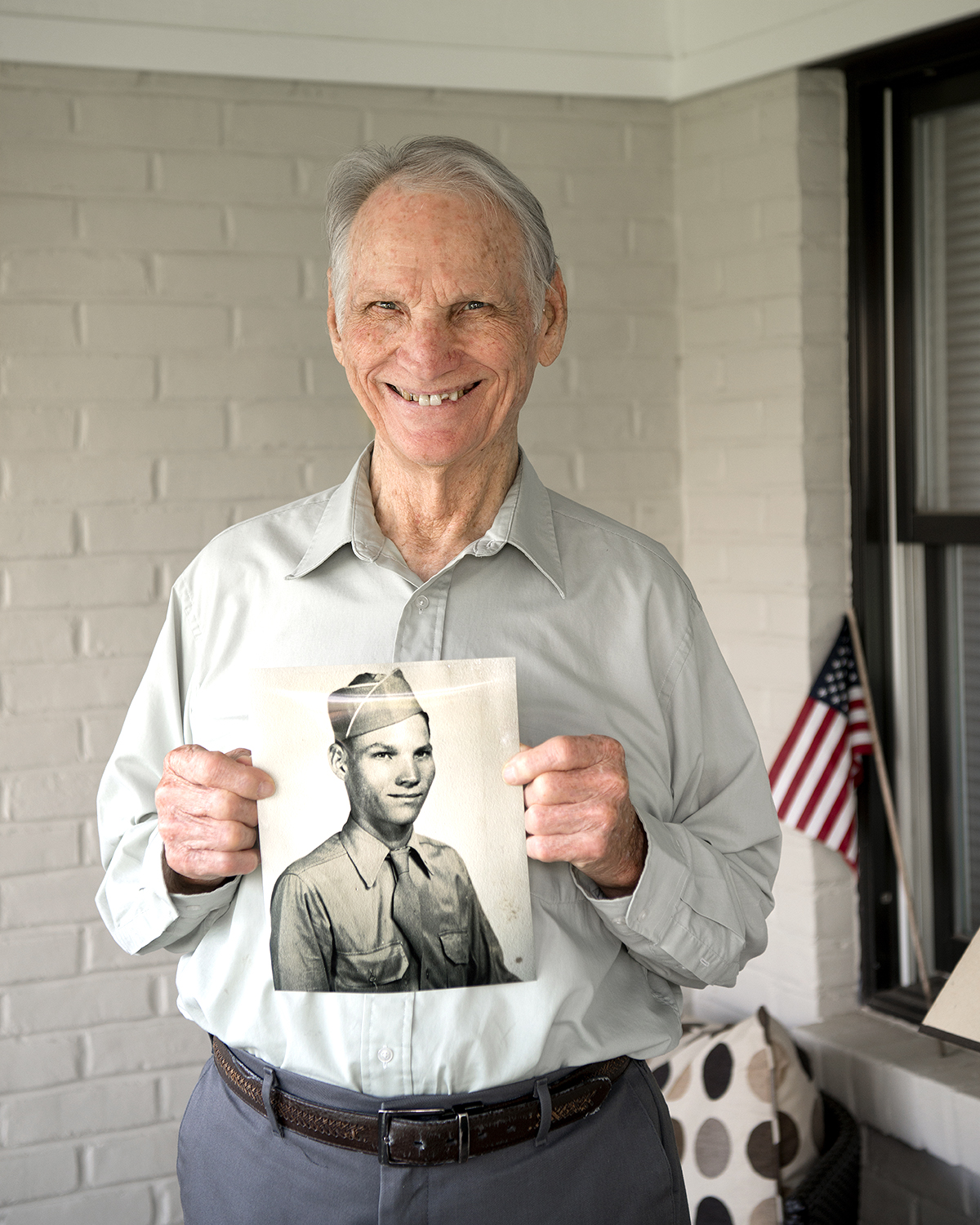

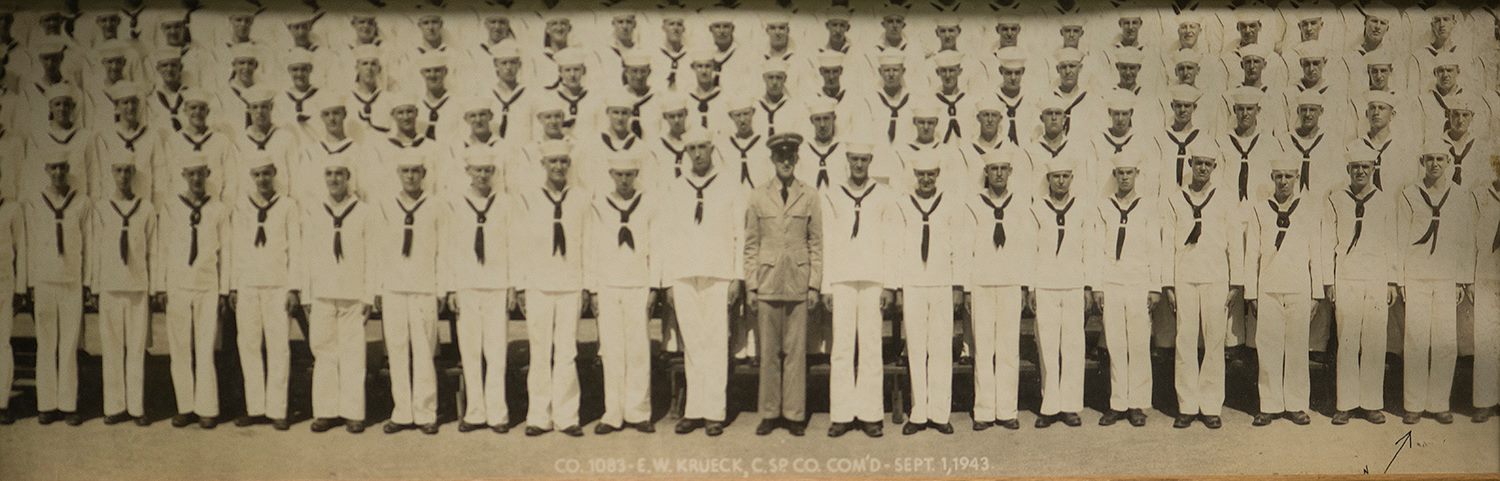

Joe Fitzwater

I was born in Terrace Park, Ohio on June 11, 1924 in my aunts house. My family lived with relatives. We were not destitute, but we were very poor. Money was not a concern of mine because I never knew I was poor at that time. From the time I was born until I was 4 years old, we lived on an apple orchard owned by a fella by the name of Ike Day. We lived in a tenants house and had a little garden that we grew vegetables in and that was our living! During that time, my dad’s wages were something like two dollars a week, plus a place to live and all of the apples we could eat and cider we could drink. Then we moved to Milford and that’s when I had my first encounter with a skunk and I was introduced to tomato juice because that’s what my mom used to try and get rid of the odor from the skunk spray. When I was five we moved to a little camp at the east fork of the Little Miami River and that’s when I started school. I went into first grade at the school in Milford and spent the next 12 years there graduating in 1942.

Pearl Harbor was a Sunday and we heard the news on the radio, but we didn’t really know what Pearl Harbor was. The next day while we were in school, President Roosevelt’s message declaring war on Japan was played over the school loud speaker. Up until that point we were very conscious of the war that was going on in Europe and wondering when we were going to become involved. It was destiny that the United States would become involved in the war, we just weren’t sure when or how. Patriotism was at such a high pitch. Today, people don’t really know what patriotism is even though they use the word. I had a friend that I went to school with by the name of Bob and I had no idea what his religion was or anything like that, but one day he was there and the next day he was gone and his cousin Loretta was also a student at our school and was in our senior class and she was gone as well. I found out that they had refused to stand and pledge the allegiance in the morning because their religion prevented them from doing that, so they were both kicked out of school. Just that simple. Today that wouldn’t fly, but back then patriotism and allegiance to the flag was very important. With the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor and our declaration of war, all of the young men were ready to join up and become heroes.

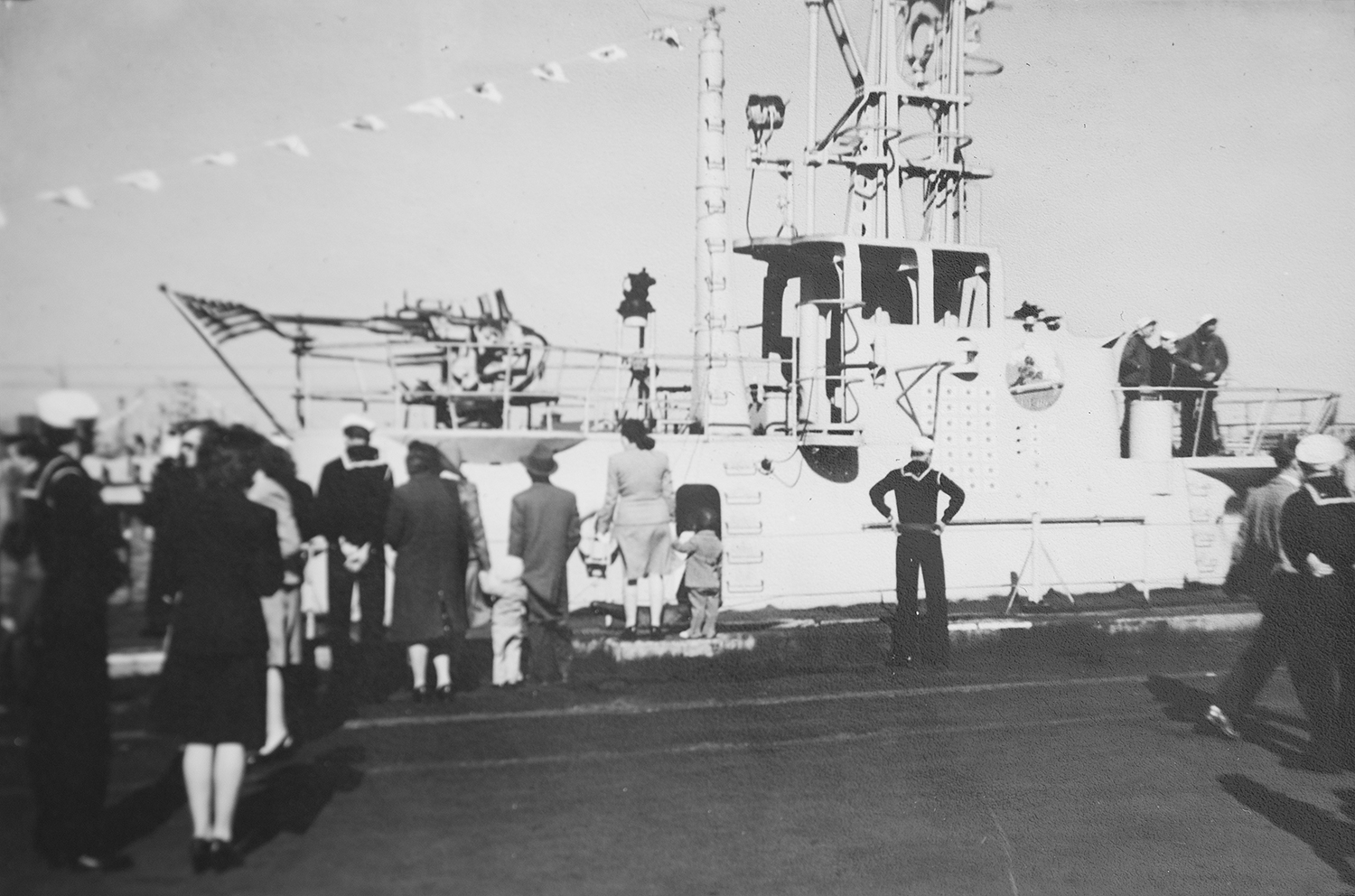

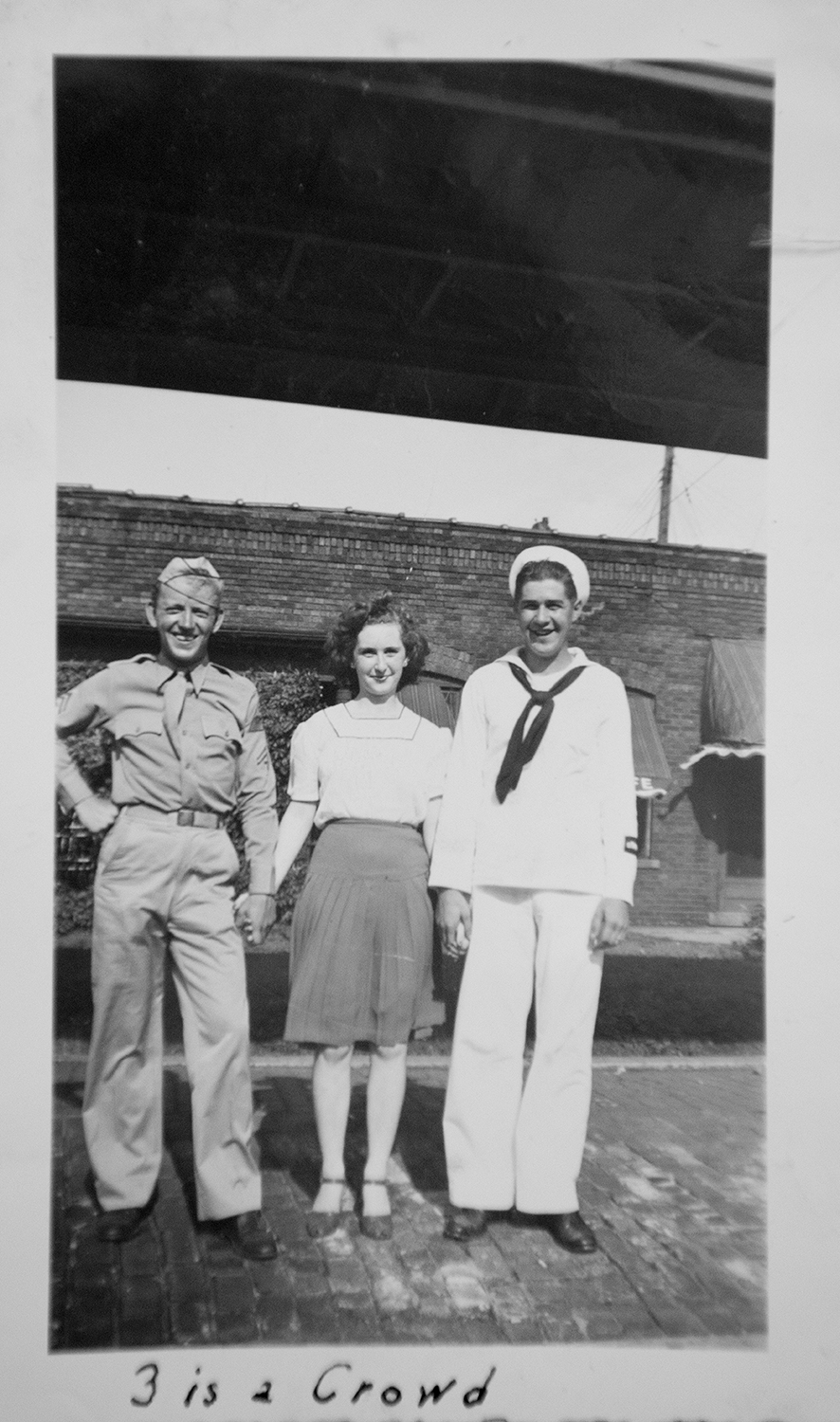

I graduated in May of 1942, I turned 18 years old in June of 1942 and I tried to enlist in the Coast Guard. My dad, who was a World War One veteran, told me to go into the Coast Guard and to not wait until I was drafted. He said it was good clean work, it’s along the shoreline of the United States and so on. When I tired to enlist in the coast guard they told me that they had all of the applicants that were needed. Apparently everyone who was older than me had the same idea as I did. So I thought to myself, well maybe I can get into the Navy! I went to the Navy and they gave me a physical and told me that I was colorblind. When I asked why they didn’t take men who were colorblind, they said the signals they used involved colors for different types of communication. Then I tried the Marines! When I walked in they laughed at me and said “We’re looking for men, not boys.” At that time I was 5’6 and weighed about 114 pounds. I was a little skinny thing. I didn’t want to go into the Army, my dad told me not to go into the Army, so I decided that I was going to just wait around until I was drafted. I went to work on the Pennsylvania Railroad working in the repair yard until I got the letter of greetings from the President of the United States that said I had been selected in the draft. On March 1, 1943 I was drafted and went to Fort Thomas, Kentucky for my induction and for my series of shots and an I.Q. test. At that time they came to me and said that my I.Q. was at a level where I could go into the Air Force if I’d like to and I said, “Oh yes! I definitely want to go into the Air Force.”

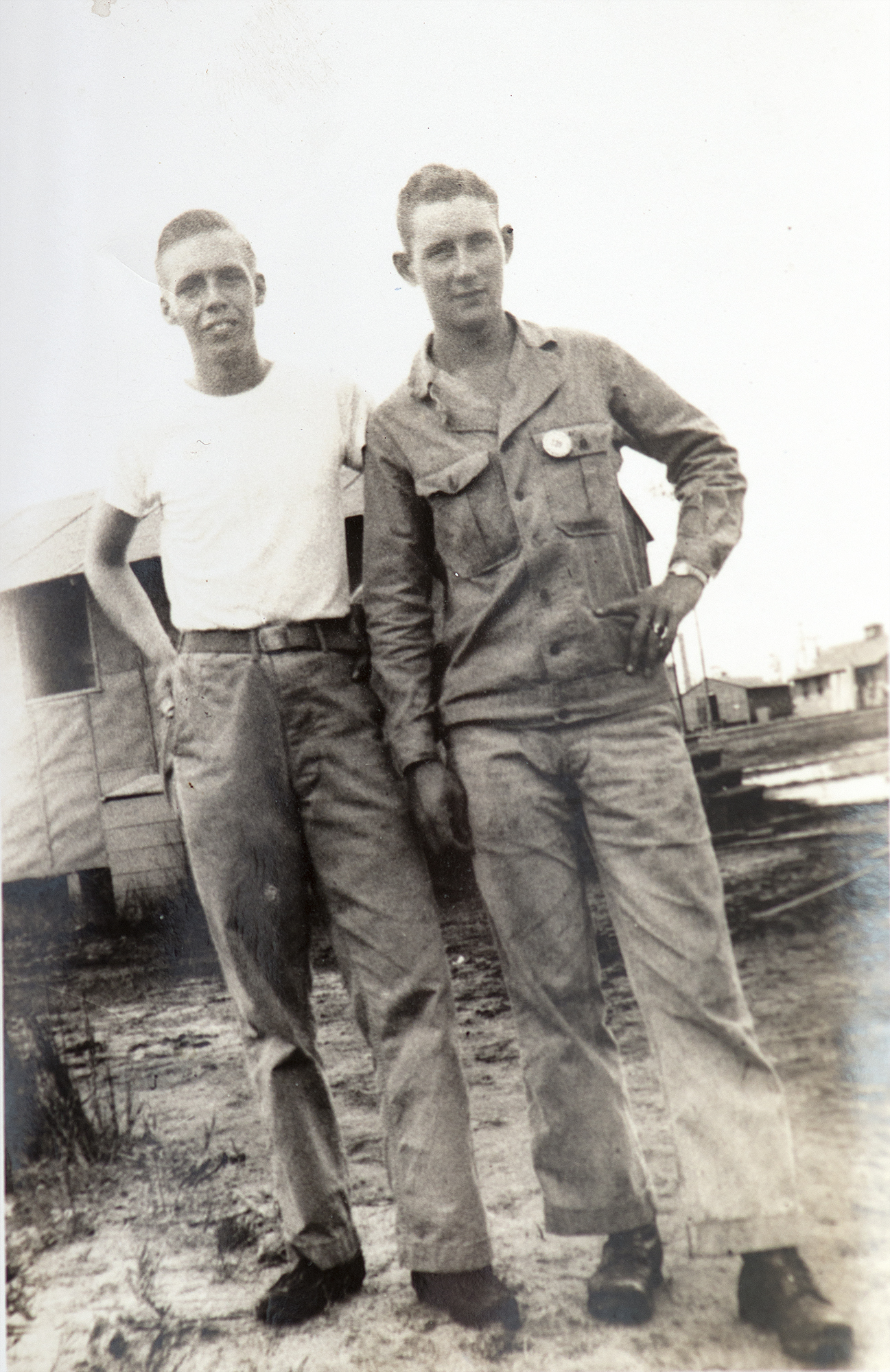

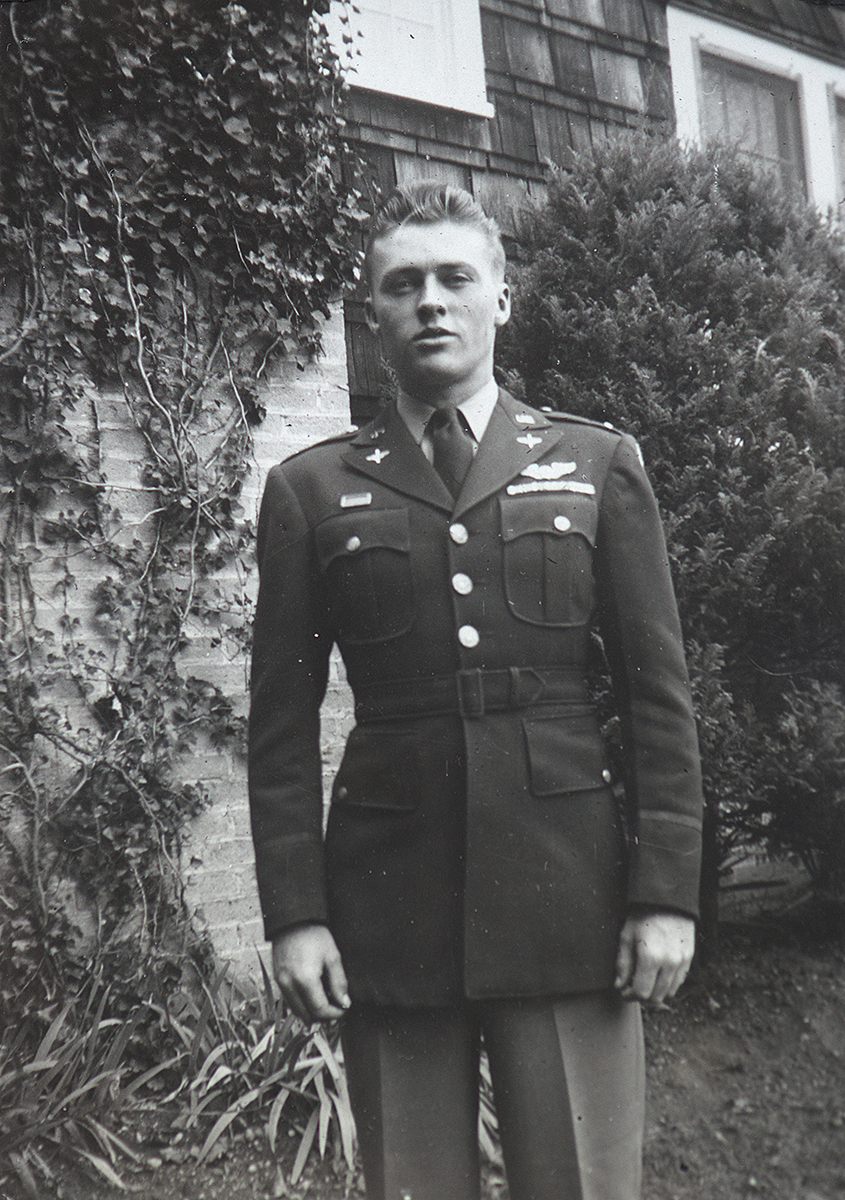

From Fort Thomas, I was sent to St. Petersburg, Florida for my basic training. Basic training at that time consisted of 6 weeks of close order drill, learning to use a rifle, taking orders and being something other than a mommas boy because they were cutting the strings from all of us country boys to become soldiers. After I was there for about a week, I was called to the officer’s quarters and they said would you like to be a pilot? I said, “Oh yes, that’s my desire, I really want to be a pilot!” And that’s what I wanted to be, I wanted to be an aviator. They put me through a mental test and a physical and in the physical they found out I was color blind again, so they washed me out. They didn’t know what to do with me because they had taken me out of basic after only a week and had told me that I didn’t need basic because I’d get all I needed in the 13 weeks of cadet school. They made me an orderly, running between different squadrons. Through being an orderly, I met a lot of people and then came my orders to go to armament school. I asked what armament school was and they said it’s where you take care of the bombs on planes and I said I didn’t want to do that. So I went to one of the officers and asked him, how I could get into photography. I had taken photography in high school and was very interested in it. He told me that it was simple and that he would write the orders for me. The orders came out and I was sent to Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado and I took the basic photography class there. Then I was called again to go to cadets. So I went and took the physical and failed again. I still don’t know why they couldn’t figure things out when I kept failing the colorblind test. I told them that I knew colors and asked them to show me colors and I would tell them what they were. They gave me a tear drop test and I passed it and was told that I could go to cadets, but then I found out that my tonsils were bad and would need to be removed first. At this time I was 19 years old. Thirty days had lapsed, which meant I had to go through the physical again and once again I flunked the colorblind test. When I got out of photo school I was promoted to a P.F.C.

I was then sent to Victorville, California where I was assigned to the basic photo lab. While I was there, my job was to teach the bombardiers how to use hand held cameras when they would drop the spotting bombs in practice, but I never got to fly. Up until this time in my life I had never flown in an airplane. I kept bugging them about flying! I wanted to fly! Finally, one day out of the clear blue sky, I get a call and they said, private, if you’re at the flight line at such and such time, we’ll take you up! For lunch that day, instead of going to the mess hall I had gone to the PX for a piece of cherry pie and a chocolate milk shake *laughs* I think you can figure out what happened next. So, we took off and we get up there and the pilot knew it was my first time up. I think he started making some turns without using any of the rudders and we were sliding around and my stomach was going back and forth and every once in a while he’d do a stall and the nose of the plane would go up and down. Well, I started feeling sick so I called to the pilot and told him I was going to get sick and asked what to do. He told me to find something to vomit in and then go back and I’ll open the bombay doors and you can drop it out. I had a brand new cap on that I had just bought, it was nice and sleek and I had paid $3 or $4 for it and at that time I was only making around $30 a week. The pilot told me to turn it inside out and use that. So I did and I dropped it out of the bombay. When we landed, the pilot inspected the plane and said that some of it had hit the plane and told me that I needed to wash the plane off. I was given a bucket, a mop and a broom and I had to scrub the entire plane and wipe it down. That was my first experience flying.

While I was out in Victorville teaching bombardiers how to use cameras, I saw an ad on our bulletin board about becoming an aerial gunner and to sign up if I wanted to become one. So I signed even though I knew they would fail me because I was colorblind. When the orders came through I told them I was colorblind and asked if they were still going to take me and I was told yes. Aerial gunners only have to be able to see silhouettes, they don’t have to see colors. I was also told that when it comes to camouflage, people who are colorblind are better able to tell the difference in shades than those who can see colors normally.

From Victorville, I was sent to San Antonio, Texas on a troop train and they gave us money for our meals and our ticket. I decided that I could make some money if I took all of my chow money and bought booze with it and sold it on the train. I was going to be a hustler, you know. All I could buy was rum, so I bought rum. No one on the train wanted to buy rum. So there I am with a bunch of rum and no food. A guy by the name of Funke said to me, Fitz, I’ll tell you what, I’ll eat two meals one day and you eat one and the next day you eat two meals and I’ll eat one. Now that is a true friend when they offer to share their food. So I’m walking around there with a bunch of rum and no money and they started playing penny ante and Funke turned to me and said, “Do you want to play?” I said, “Man I’m broke!” He said, “I’ll give you a quarter!” So I got in the game and I won and I won and I won and I ended up with about $14, so I was back in the money! So I’m walking around with all of that money in my pocket and I see a couple of sergeants playing blackjack. I walked up and asked if they were looking for anyone else to play blackjack and they said yeah, sit down kid, sit down! I sat down and won $128! After 4 days on the train, we arrived in San Antonio, it was late at night and there was an 11 O’Clock curfew for the military, you weren’t allowed on the streets after 11. They didn’t know what they were going to do with us and I said, “My guys”… and I say my guys because I was rich… “My guys and I will stay at a hotel, can you get us a hotel?” The MP’s said, “Yeah sure we’ll take you to a hotel!” They took us right to a hotel on the canal in San Antonio. The rooms were $2 a night and two guys could sleep in each room, so it only cost me $8 to be the big time Joe, you know? We didn’t have anything to eat either, so we asked where we could get something to eat and the MP’s said, “Well we can go to a restaurant and get you guys some sandwiches if you want.” I said, “Here’s the money go get us some sandwiches, I’m really big timing it!” They came back with some chicken and beef sandwiches. The next day we loitered around San Antonio and the canal until we had to get back on the train, which took us to Brownsville, Texas, right on the border of Texas and Mexico. Brownsville is where we took our aerial gunnery training. I took top turret gunner training for either B-24s or B-17s, I didn’t know which I’d be in. Most of our training in aerial gunnery school consisted of shooting from the back end of trucks. We would be moving while shooting with shotguns and the target would be stationary. From there we went to moving targets that were on a rail and we would have the 50cal machine guns. During this time the target would be moving and we were stationary. Then we got into air to air target practice. I got air sick the first 11 times I flew. Luckily I found out that I could use the empty 50cal machine gun ammo cases to heave into. I finally overcame that. I graduated aerial gunnery school and we went to Lincoln, Nebraska for crew assignment to then go overseas.

My assignment while we were in Lincoln was to keep the pot belly stoves in the tar paper barracks stoked at night. One day I finished up around 8 in the morning and I got a note to report to the Lieutenant as soon as possible. So I took a shower, got cleaned up and put on khakis and went to the building I needed to report to. I walked in and there was an orderly sitting there and I said, “I’m Private First Class Fitzwater, I’m to report to Lieutenant Early. I don’t know what this is about.” He said, “I don’t either, just a minute.” He went in and came back out and said, “You can go right in Private.” I walked in and came to attention and said, “Private Fitzwater reporting as ordered, sir!” I see feet sitting up on the desk and there was one of those round lights that hung down from a cord and I couldn’t see under that. Well here sits Roger Early from Milford, my home town and he’s the Lieutenant. He said, “How are things in Milford?” I ducked down and looked and thought to myself, what is this? I suddenly realized who it was and thought to myself, man, I just stepped into heaven here! I’ve got a friend who’s an officer! So I sat down and we talked and he asked, “Where are you going when you leave here?” I said, “I don’t know, but I understand that I’m going to be in B-24’s.” He said, “What’s your job?” I said, “I’m a top turret gunner” and he said, “Well let’s look things over here” and then said, “You know, there’s a place in Kentucky or Tennessee, I forget where it was, where they are doing overseas training. How would you like to go there?” I said, “Boy that would be fabulous!” Roger said, “And on the weekends you could probably get yourself a pass and get home every now and then.” Man that would be good!

So I left there and got my orders. I was assigned to Mountain Home, Idaho, 2,300 miles from Milford. Mountain Home, Idaho is where our crew was formulated and went through our overseas training program, getting us ready to go to Europe. We knew we were going to combat in Europe. At the last minute, orders came through sending us to Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma because I had photographic training and they needed aerial photographers. In Oklahoma City, we went through aerial reconnaissance and mapping for three months. Our co-pilot had injured his shoulder and we got a new co-pilot and we had to go through the training again for the new co-pilot, adding another 3 months. Finally we were ready to go overseas and be heroes! Everybody wanted to be heroes and get the medals. We were ready to go overseas and they ship us to Salinas, California. This is 1945 by now. I’ve been in training all of these years, training, training, training and they drop the bomb and Japan surrendered. The war was over so we didn’t have to go overseas. Well, we were wrong. They sent us overseas. We were given a brand new B-24 photo camera plane. In these planes, the bombays were eliminated, the doors were sealed shut and the photographic equipment was installed there. There were two cameras, one on each side of the bombay, that were fixed and set up to take photographs simultaneously. This was when we started using topography and this was 2-dimensional. With glasses and the processing we did, we could capture the height of things on the ground as long as we weren’t too high in altitude.

After flying across the Pacific, we landed at Clark Field in Manila in our brand new B-24. When we picked that plane up, it was so shiny and pretty, and they had only clocked 4 hours on it while testing the mechanics. They took our plane away from us and we said, “Hey where are you going with our plane?” They said, “Well we need that plane. That plane can make ten other planes fly. We can get enough parts off of it to get 10 other planes serviceable.” So we get some dumpy old plane assigned to us and then flew down to Palawan, 400 miles south of Manila. From Palawan, we did aerial mapping of Mindanao and Borneo and other islands in that area that had never been mapped before. But there were still Japanese on these islands who didn’t know that the war was over. So those Japanese soldiers were down there with their rifles and machine guns firing at us as we flew over. These interactions were never serious. We had a few bullet holes in our plane from time to time, but no one ever got hit. I was also the back up pilot on our crew in case the pilot or co-pilot got injured or killed. I was trained to fly the plane, but I never landed it. I ran the base lab and processed all of the photographs even though I wasn’t the only photographer there. My crew was in the 2nd Reconnaissance outfit. The two films had to be aligned when you printed them so you could get the right image. When they decided to close the base, they said, “Well you’re going home.”

Right before we were supposed to come home I got jungle rot. It really started getting bad and I tried cutting my shoe away so I could walk, but they sent me to sick bay. Coming home wasn’t nearly as nice because they put us on a Liberty Ship with the real round bottoms and it didn’t cut through the waves, it rode over top of them. I got so sea sick, oh my goodness.

When I came home I stayed out for a year, but was in the reserves. I didn’t like civilian life. I had various jobs and none of them were very satisfactory, so I called the recruiter in Cincinnati and asked if they were looking for photographers. He asked what my category and MOS was and I told him and he said yes. I asked if I would get my rank of Staff Sergeant back and he said, “Yes, we need you.” So I went down and I was ready to sign the enlistment papers and I saw Corporal on the line that stated my rank. I said, “Woah, that doesn’t say Staff Sergeant, I’m not signing it, if I’m not a Staff Sergeant I’m not going back.” He told me to wait a minute and went into the other room with the officer and they used a little white out and when he came back in it said Staff Sergeant on there, so I reenlisted. This was March of 1947. The year of 1947 is also when the Army Air Corps was dissolved and the U.S. Air Force was formulated. Those of us in the Army Air Corps had to be discharged and reenlist in the Air Force. They sent me to Chanute Field, Illinois where I was reassigned to the photo unit at Eglin Field in Florida. When I got there, due to the fact that I had flown during World War Two and had some experience in planes, they put me in the motion picture section of the photo lab and that’s when I got acquainted with motion pictures. We were using 35mm and 60mm film on hand held cameras. We were testing a camera, an A16 I think, that held one hundred feet of 35mm film. They sent me up in a helicopter to do it and those helicopters were such rickety rough things that when you got back and processed the pictures you would get sick just looking at them! To solve this problem I went and got some old inner tubes and placed them in four places around the door of the helicopter and then I had the machine shop on our base make me a base plate for the bottom of the camera and connected those things up and tightened up the straps. When I processed the first roll of film after using my new contraption, it was just as smooth as it could be. I also ran the 16mm Kodachrome. While I was in Florida I was confronted and asked if I wanted to attend OCS at West Point. My I.Q. had qualified me as one of the enlisted men in the U.S. Air Force to go to West Point. I said, “Okay well let me talk to my wife.” They said, “Your what? Sorry, married personnel can not go to West Point.” So that took care of my West Point adventure.

One day my captain came in and he had a corporal with him and he said, “This is Corporal Nelson, he’s going to be your assistant.” I said, “I don’t need any help.” The captain said, “Well he’s going to be your assistant anyways. He needs to learn how to operate this machine.” Nelson stayed with me 3 or 4 months and became real close to me. My wife was pregnant at the time and when our daughter was born, Nelson had his own car, and I should have known something was up then when he had a brand new car. He offered to bring my wife and baby home, which he did. He started having meals with us and it felt like he was almost like a brother. I didn’t think anything about it and then I got a phone call from my mom and she said, “Junior, are you in trouble?” I said, “I don’t think so.” She said, “Well the F.B.I. is up here asking questions about you.” I told her that I was not in trouble and that I hadn’t done anything. Even at this time nothing had registered in my mind. A couple days after that I went to work and Corporal Nelson didn’t show up. I asked the captain if he knew where Nelson was and he said that Nelson was reassigned, but he didn’t know where. A week later I was called in and the captain told me that I had been cleared for top secret access in the rocket program. I had no idea that the F.B.I. was investigating me this entire time. They had projects that needed to be photographed and someone had to have a top secret clearance before they could shoot the photos that were needed. I was then told that I needed to take an oath, which I did. My job dealt with both still and motion picture work. I would go up in planes to shoot motion picture work and we would come in to land, I would be met by two M.P.’s and a major or higher ranked officer and they would escort me, my equipment and my film back to the base photo lab. The officer would go into the lab with me, I would set up the sprocket hole counter, turn it to zero, turn the lights out, I’d put the film in and run it through, put it back in the can, turn the lights on and he would take the reading of how many sprocket holes there were. He would then leave and I would process the film. If I had to break or splice the film, I had to save everything. The officer would come back in after everything was processed and dried, I’d have to run it backwards through the counter and if it came out to zero, everything was fine. I would then be given a receipt for the film and he would take the film and the can and the two M.P.’s would escort him out of the photo lab and they were gone. That’s how much I knew about what I was taking pictures of. I had ideas, but if anyone was to question me and for me to reveal secrets about what we were doing, I couldn’t have done it. In fact, I didn’t know what was top secret and what wasn’t.

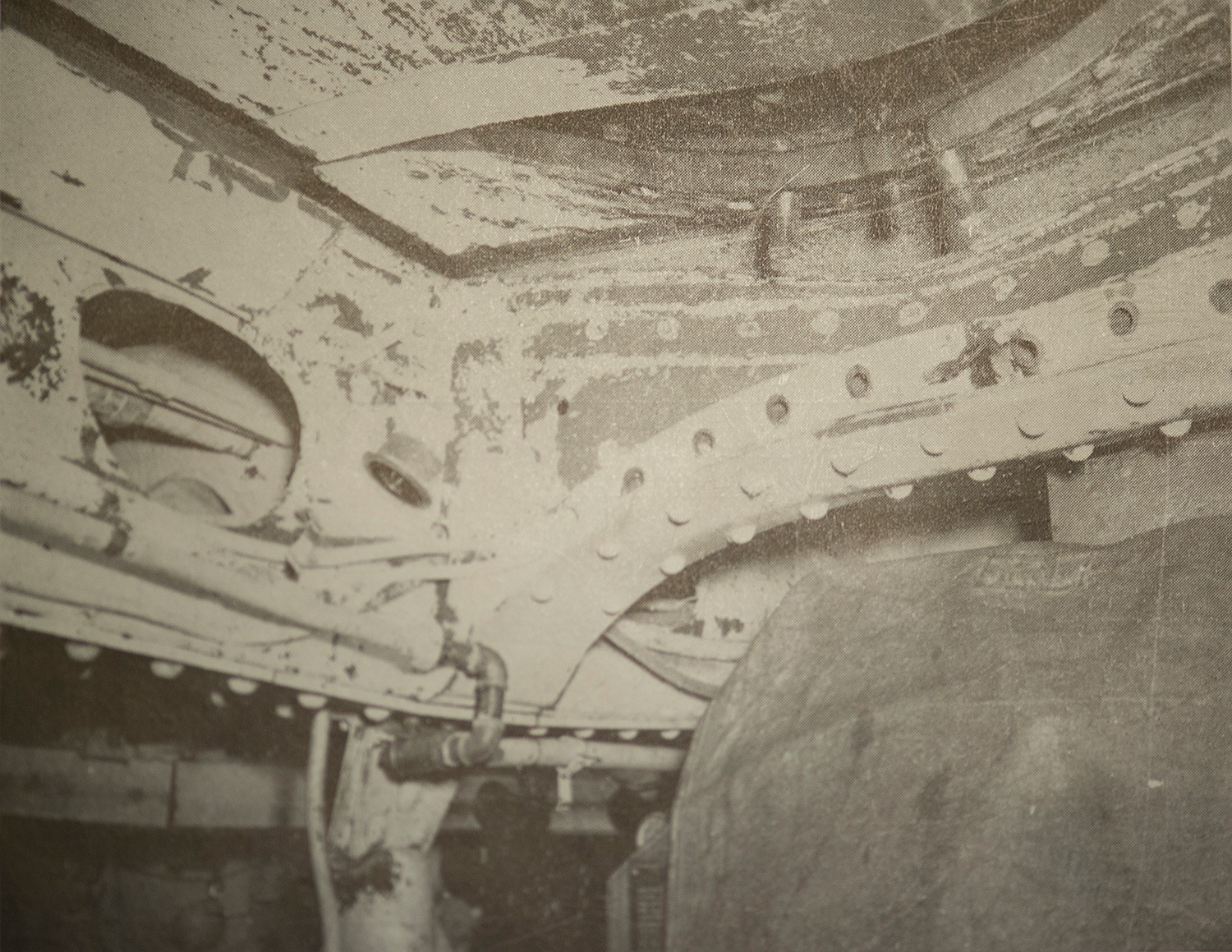

I was in so many close calls flying the way we did and I flew in every type of airplane that the Air Force had that sat more than the pilot. I flew in the jets, bombers and helicopters. I shot a lot of motion picture work over the pilot’s shoulder of rockets and I would take pictures of the bombs when they would hit the targets. There were instances where we couldn’t get the bombs out of the plane because what we were testing didn’t work and we’d have to land with the bombs still on the plane and the pilot would say, “If anyone wants to bail out, I’ll fly at 2,000 feet and slow the plane down as much as I can and you can bail out.” We had some instances where one bombay door would open and the other wouldn’t and we couldn’t drop our load. One day we came in for our landing and we couldn’t get the nose gear on the B-29 we were in. We tried cranking the gear down and we couldn’t. The pilot gave us the opportunity to bail out. Eglin Field was on high alert. I asked the pilot what he was going to do and he said, “I’m going to land the plane.” I said, “You’re not going to bail out?” He said, “No, I have never been able to see the benefit of bailing out of a perfectly good airplane.” I said, “I’m with you then, I’m going to stay with you.” We came in and landed and our nose gear touched, it completely folded up and we were on our nose, but it was a successful landing.

One day we were up and we had eight 1,000 pound high detonation bombs and were going to drop it on a target out over the Gulf of Mexico. We were going back and forth over the land and water and I was sitting there looking out of our little observation window into the bombay and saw that the tail fin on one of the bombs was spinning. The armor gunner was sitting next to me and I said, “What is that?” He looked through the window and his eyes got real big and he reached up and hit the salvo button. Seven of those bombs fell safely out of our B-29, but that one didn’t, the arming wire had been pulled out of it. So when we landed, we were met by the attorney general of the base. One of the bombs had landed really close to a town and blew one of the paint off of all of the cars, but didn’t hurt anybody. These little instances kept happening.

By this time my wife and I had our daughter and these dangerous situations kept happening. I said to myself, “This is not combat, but it certainly feels like it.” So, one Sunday afternoon I was supposed to fly and I went out to the base and checked in. One of my fellow photographers was there, Sergeant Bell and he said, “What are you doing today, Fitz?” I said, “We’re going to use the Lands Camera for some instrument work while we check some engines out. We have to photograph the readings on the dials for the pilot because we were using 4 different carburetors on 4 different engines on the B-29.” He said, “Classified?” I said, “No, not classified.” He said, “Well I don’t have my flight time. We had to have 4 hours time to get flight pay.” He said, “Can I go in your place?” I said, “Sure! Go right ahead.” I was getting in so many hours at that time that it wasn’t funny. I turned around and went back home. The next morning I came back on base and walked into the orderly room and I get this stare… everybody stopped what they were doing and were looking at me. I asked what was the matter. Someone said “What are you doing here?” I said, “What do you mean what am I doing here?” They said, “Didn’t you fly yesterday afternoon?” I said, “No, Sergeant Bell flew. He needed the flight time.” The plane that I was supposed to be on crashed and everyone was killed. That really shook me up. I was within moments of death. Had Sergeant Bell not needed his flight time, I would have been on the plane. This was on top of all of the other things that had happened to me while documenting in planes. I got out of a helicopter one time and they were going to move it and they took off and it got up 90 feet and the engines quit and it came down and crashed and both of the men on board were killed. I had just gotten out of it and I was still running. I thought to myself, “How many more messages do you have to get before you get it in your thick skull that you better quit flying? So, I went to Major Newbert and I said, “Major, I’m going to quit flying.” He said, “No you’re not, Sergeant.” I said, “What do you mean, no I’m not?” He said, “You’ve got top secret clearance, you’re the only aerial motion picture photographerin the Air Force with a top secret clearance.” I asked why and he said, “They aren’t needed for much, there are only two places they are used and we are doing all of the classified work here.” I told him, “I don’t want to fly anymore, you know I was supposed to be on that flight, I’m not going to fly.” He said, “Well if you don’t want to fly, you give me no option but to court martial you.” I said, “Well if you have to, then you have to. I think a court martial takes preference over taking anymore chances while flying.” He dismissed me, I stood up and saluted, about faced and was heading towards the door and he said, “Now Fitzwater, come back here and sit down.” He and I were good friends off base. I didn’t have a car at the time and he would let me borrow his car when I needed to use one. I sat back down and he said, “This is not the way we do it. We’re going to do it a different way.” He called the flight surgeon and said he was going to send a sergeant down to him and asked him to give me a medical waiver on flying. So I went down to the flight surgeon and they had worked it out to where I didn’t have to fly anymore, but they said that I was now permanently grounded and I would never fly again for pay. I told them that was exactly what I wanted. I said, “I love flying, but I’ve had too many close calls. One of these days that close call is going to be the last call I get.” My wife agreed with my decision because she didn’t want me to fly anymore either. Things went along fine for a while and then I got another call and they said I was going to Korea.

We had been testing napalm bombs at Eglin Field while flying 10 test missions a day. I was flying in helicopters taking pictures of the area the napalm covered when it hit. They were going to use napalm bombs in North Korea and I was going to be tasked with going up in helicopters for 10 days to record the results during actual combat. I said, “You’re telling me I’m going to get up in a helicopter and get shot at while these bombs are being dropped below me and take photographs?” They said, “Yep, that’s what you’re going to do.” I said, “And what if I don’t?” They said, “Then it’s treason. You don’t have a choice, you can not refuse this.” I was told, “You can’t tell your wife.” When I got home that night I said to my wife, “I’m going to be gone for 30 days, so you might as well go home.” She said, “Where are you going?” I said, “I can’t tell you.” She was so upset and didn’t understand why I couldn’t tell her, but I was sworn to secrecy. We had our own ship and 6 jets, we had our own air crew and ground crew and one helicopter. While we were out in California waiting to get on our ship, MacArthur got to the Yalu River in North Korea and they called the mission off. The good Lord had been watching over me, let me tell you!

When I arrived back in Florida, I was just excess baggage and was then sent up to Newburgh, New York where I ended up not being needed. So then I was sent to McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey and was put in the base lab there, which was very satisfactory. Any time there was a crash, they’d send me to the location to document it because if it was classified material, I still retained my classified access, so I could take pictures of anything, any place, any time. That went on until the Air Force decided I needed a little more overseas time because I had been in the Air Force all of these years and only had 6 months overseas. They want at least a third of your time in the service to be overseas. They were going to send me to Alaska and Alaska was not a state at that time and my wife was pregnant with our second daughter. I said I know that my daughter is going to be born. I don’t want to go and I don’t have to go. I didn’t have to go, but as soon as my daughter was 30 days old, they sent me to Mountain Home, Idaho again. I get out there and I’m excess baggage and I ended up being a First Sergeant, which I didn’t want to be because I was a technician, not an administrator. I kept that position until I had enough time in to resign. I resigned in March of 1953 and that terminated my military career. I had a very interesting military life, I had some close calls and most of it was rewarding, but I don’t regret any of my military life.

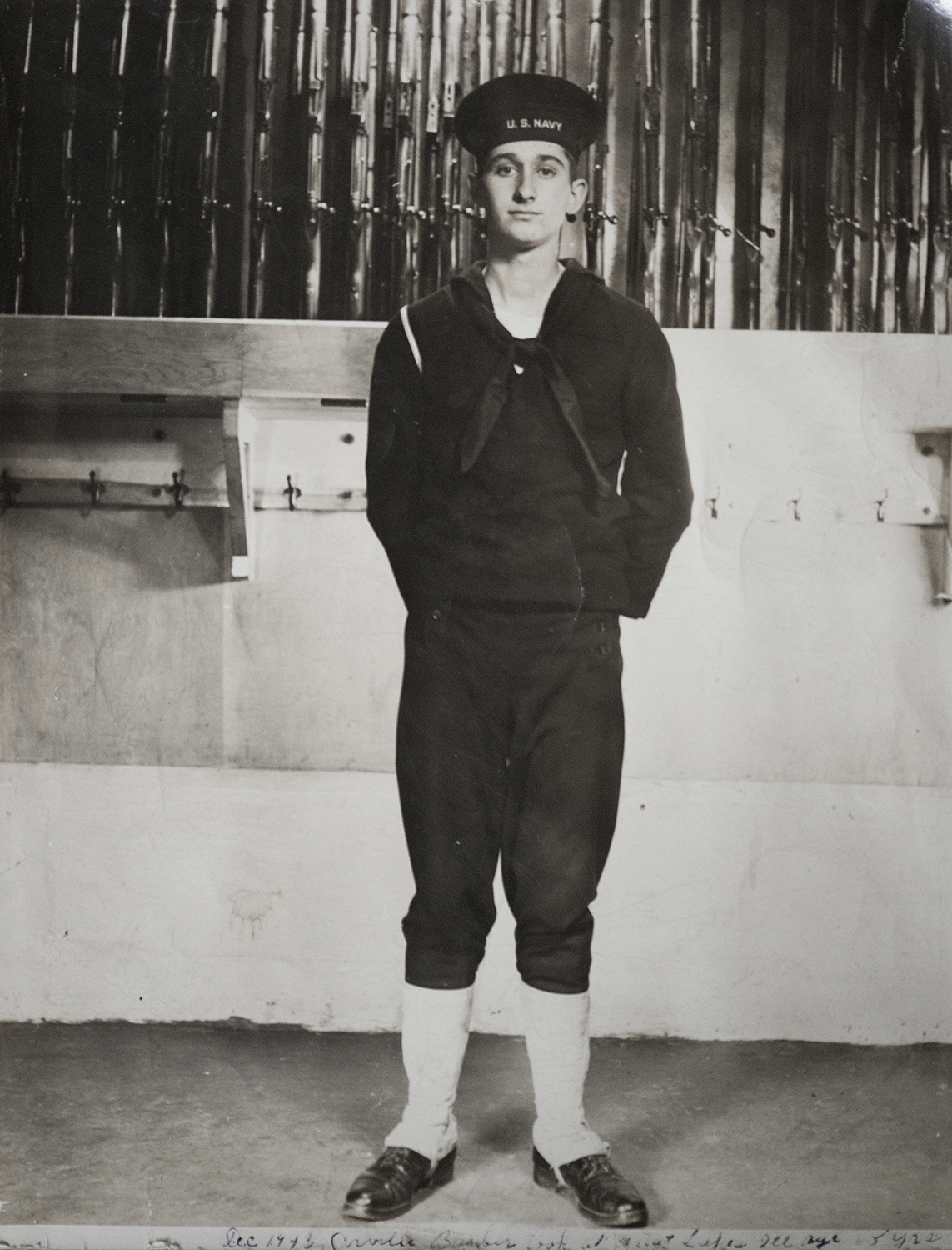

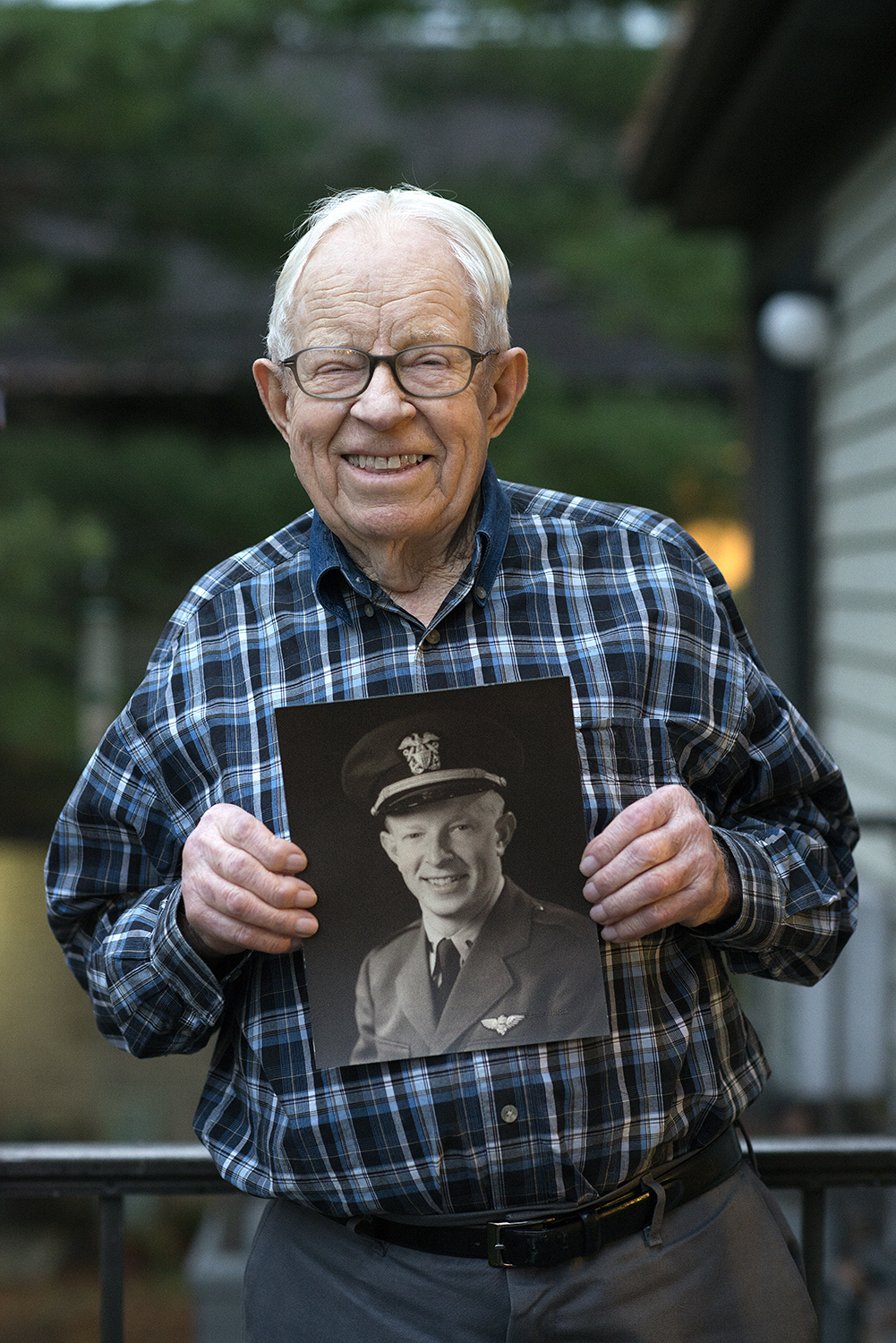

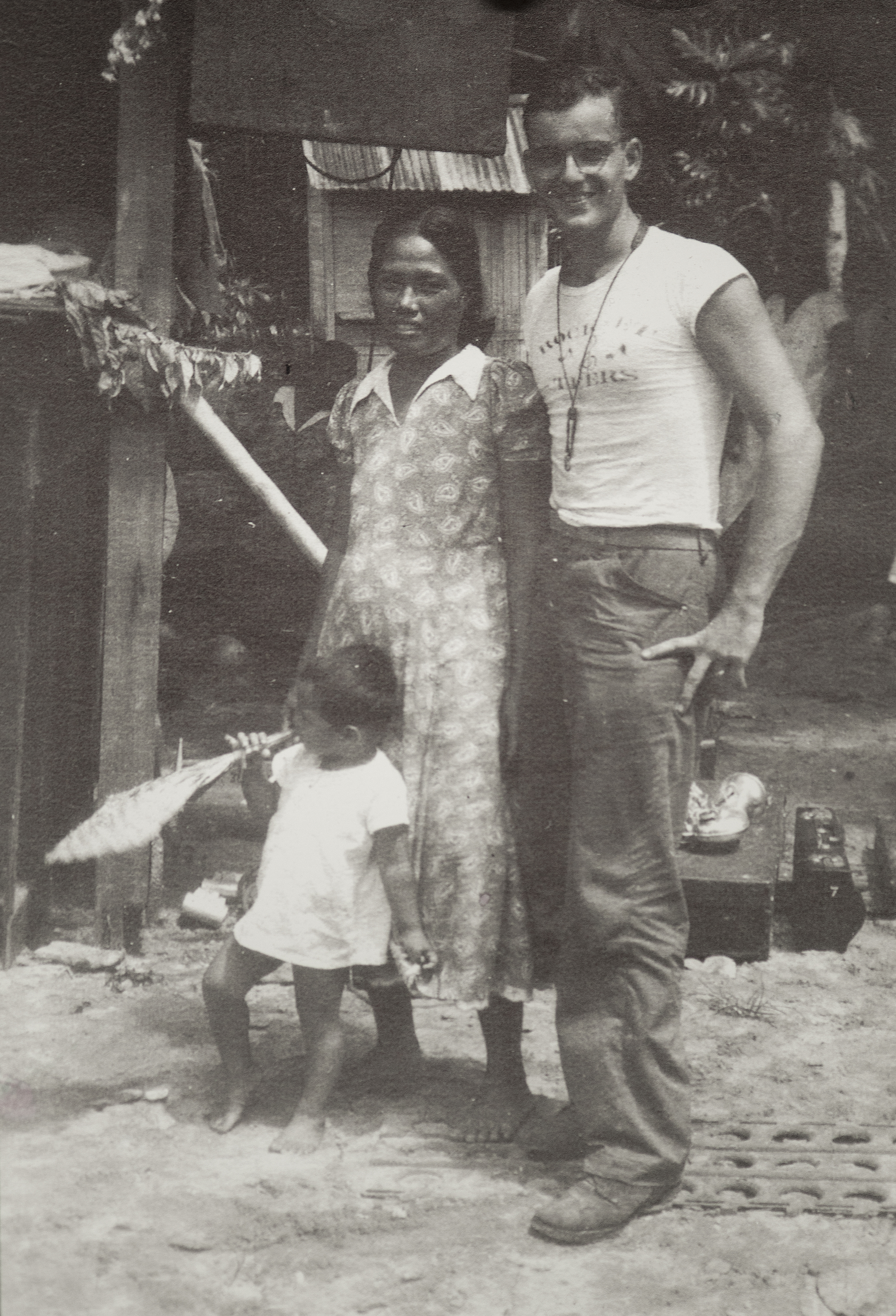

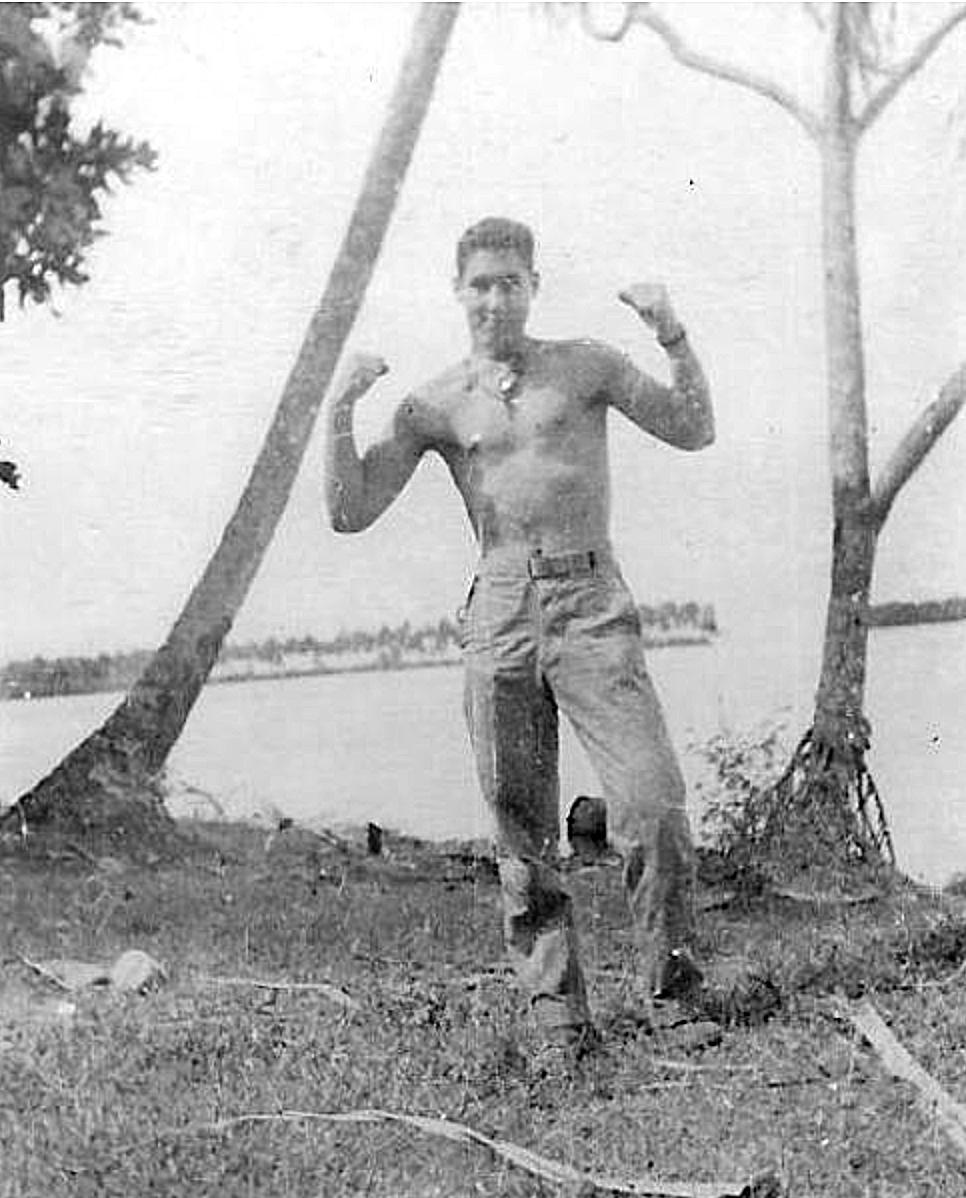

Bo Gallo

I was born in Columbus, Ohio November 6, 1920. My dad was an immigrant from Italy and had his own tailoring shop. My mother worked for him as a seamstress. Growing up during the depression was rough, real rough. I worked as a shoe shine boy from the time I was in the fourth grade, full time after school and in the summer and the money I made went home to my family to help out. I also had other odd jobs helping out at the grocery store and things like that. I never resented it because I knew what I was doing was helping my family, I was willingly doing it. You just made your way.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, I was right here in Cincinnati. I was going to spend the week here when the attack happened. A friend of mine was heading back to Columbus the next day and I said, take me back with you. The next day I was back in Columbus. I knew a gal that worked in the military office and I asked her if she could give me a heads up to let me know when I was going to be drafted, but she told me she couldn’t do that. So I said to her, can you just give me a call and say, Hi Bo, this is so and so, and just hang up? She said she could do that. It wasn’t too far down the line that I got the call. I thought to myself, if I go and enlist, I’ll have a better chance of being taken care of when the time comes for me to be shipped out. I was drafted into the Signal Corps within a month of the United States joining the war. Every order I got from that time on ended up being good for me. From Columbus I took a train out to California and as we passed under the Arlington overpass, I remembered the girls I had dated and the friends I had and thought to myself, I wonder if I’ll ever see this place again.

Following my time in California, we were stationed in Hawaii for a while and were the first troops there after the Japanese attack happened. The people there were very nice. Then we were back in San Francisco for a little while where I was with the cadre. It was a bunch of technicians and that’s when we formed the 191st Signal Repair Company. When we finally shipped out, we were on the ship for 40 days while crossing the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco to India. I had never been on a ship before and it was rough! Everyone got sea sick. Life doesn’t get any worse than traveling on a troop ship across the ocean. Space was extremely limited, there was no air conditioning, and no lighting. The food was horrible, but we were fed. Our chow line was straight and then you did a quick right and bingo! There was the food right there. So I was talking to this guy in front of me one evening while we were waiting in line for dinner, so on and so forth. When he made the turn in toward the food, I saw that something hit him and he got sick and threw up into his mess kit. He turned and walked back by me and some of the guys who didn’t see what I had seen said, my God do you see what they are serving us for dinner? Another guy said, It looks just like puke! I turned and said it is puke! It was pretty funny and you laugh about things like that because there really isn’t any other way to go about it. Later on during the trip we had a submarine sighting and everyone was ordered to their battle stations. My station was 5 levels down. As soon as we got there they began closing all of the doors one by one. Then the doors were locked and the lock was on the outside of the door not on the inside. One guy turned to me and said my God Gallo, how do we get it open? I said we don’t, what we are going to do though is pray! The reason they did that was in case the ship was hit and the hope was that it wouldn’t sink and the losses would be limited.

When we reached India, my unit was stationed on the Ledo Road and the Burma Road and I was assigned as the supply sergeant. During my time there I contracted jungle rot on my feet, ankles and hands. At first I turned down the medical staff’s recommendation to go to the hospital because I wanted to stay with my outfit. The medical officer said to come back in two days for a check up. When I came back two days later, I was in even worse condition. He looked at me and said, Sergeant, any more comments from you and I’ll have to Court Martial you. I was hospitalized. When I recovered I was sent to a divisional office where they were going to reassign me to a new company. Well, I was worried I wasn’t going to be with my buddies anymore, so when they released me from the hospital, they gave a driver my records and told him where I needed to report to. When we started driving, I asked if there was anywhere along the route we were driving where we could get onto the Burma Road. He said yeah! I asked him to drop me off and he told me no, that he had to take me to the new station they ordered me to go to. Then I asked him if they had any other records besides what was in my hands and he said no, so I said drop me off please! He dropped me off. After he dropped me off I made my way across India and it took me 20 days to find my unit. When I walked in, this one guy said, where in the hell did you come from Gallo? You’ve been dropped from everything! I said, I’ve been on a long damn trip! Because I was in uniform, I was able to get rides in cars and on trains and at one point I even ended up on a raft in a river. All I could think of was that if the raft failed, no one would ever know what happened to me. I was really lucky to find my unit!

There was a guy from Texas that had taken over my job as supply officer when I was hospitalized and I didn’t like him at all. I walked in the next morning after reporting to the commanding officer and he looked at me and said what are you doing here? I looked at him and said, I’m here to take my job back! Get your tail out of my supply office! He got up and left and we didn’t have any problems. I was back where I belonged.

The weather in Ledo was hot and humid and uniform discipline didn’t exist. Guys would walk around with no shirts on and some had cut their pants into shorts. It didn’t really matter what you wore, but when we had to dress properly, we all got back into our uniforms.

There were some guys that were flying from Ledo over the Hump to supply other bases where we had stations set up. On one of these flights, there was a guy named Jonesie that I knew and I gave him hell because he was flying the mail because it gave him an extra $20 a year, but he was an only child. Before their flight took off that day I caught him in our compound and I said to him, what the hell are you doing? He said what do you mean? I said damn you, you’re an only child, you can’t be flying missions like this and he said okay okay, get off my back, get off my back, I’m turning in my pistol tomorrow and that’s going to be it. I looked at him and said if you get back on that plane again, I’m going to kill you! The next day while flying the Hump, the plane crashed and he was killed. We sent a group out to try and find the plane. I wanted to go, but was denied permission to go on the search flight because I was still dealing with the jungle rot and I’m glad because the search flight that was out searching for Jonesie’s plane ended up crashing as well and everyone was killed. The territory in that area was very difficult to navigate and if anything went wrong you were in rough shape. We lost many many planes to the terrain. It was bad.

When the Japanese surrendered, I was close to a railroad station and someone heard the news on the radio. The train engines were going up and down and they were blowing the whistles in celebration. One guy was yelling, “It’s on the air, It’s on the air! The war’s over!” Yet the commander of that area wouldn’t tell us anything. He said as far as we were concerned the war is still on! I don’t know why he did that, but he held it up for half the day.

After the Japanese surrendered and the war had ended, our commanding officer ordered me to make a flight to deliver the paychecks. I asked what the rush was and he said he just wanted it done. I said, I’m not flying. He said what do you mean you’re not flying? There is no way I’m going to get on the plane with this horrible weather we were having. You can Court Martial me! He said, well I order you! I told him to go right ahead and do it! Nothing ever came of that and I didn’t make the flight. I’ll never know why he wanted that done, but I wasn’t going to fall to it!

Fortunately for me, the trip home very good. We flew from where we were stationed in Ledo to a port where we boarded a ship. The trip took 15 days and we arrived back in the states in San Francisco. From there I took a train home. My two brothers also arrived back home at the same time. I was exhausted and in rough condition and I was taking Atabrine. My mother took one look at me and almost dropped to the floor. I said don’t worry mom, I’m alright! I’ll get along! There was a nice celebration for my brothers and I though! Everyone congregated at our house and there was a feast. I still look back and thank God that we all came home. It was an absolute miracle.

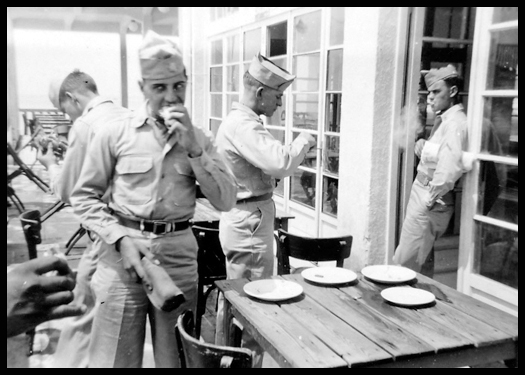

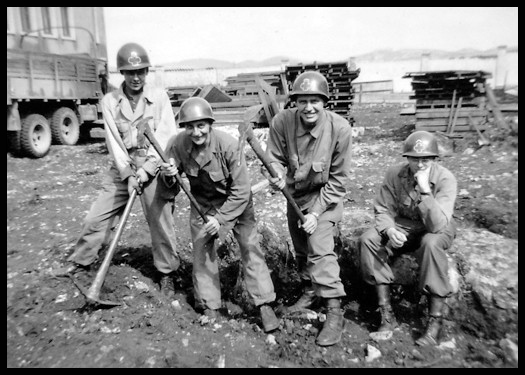

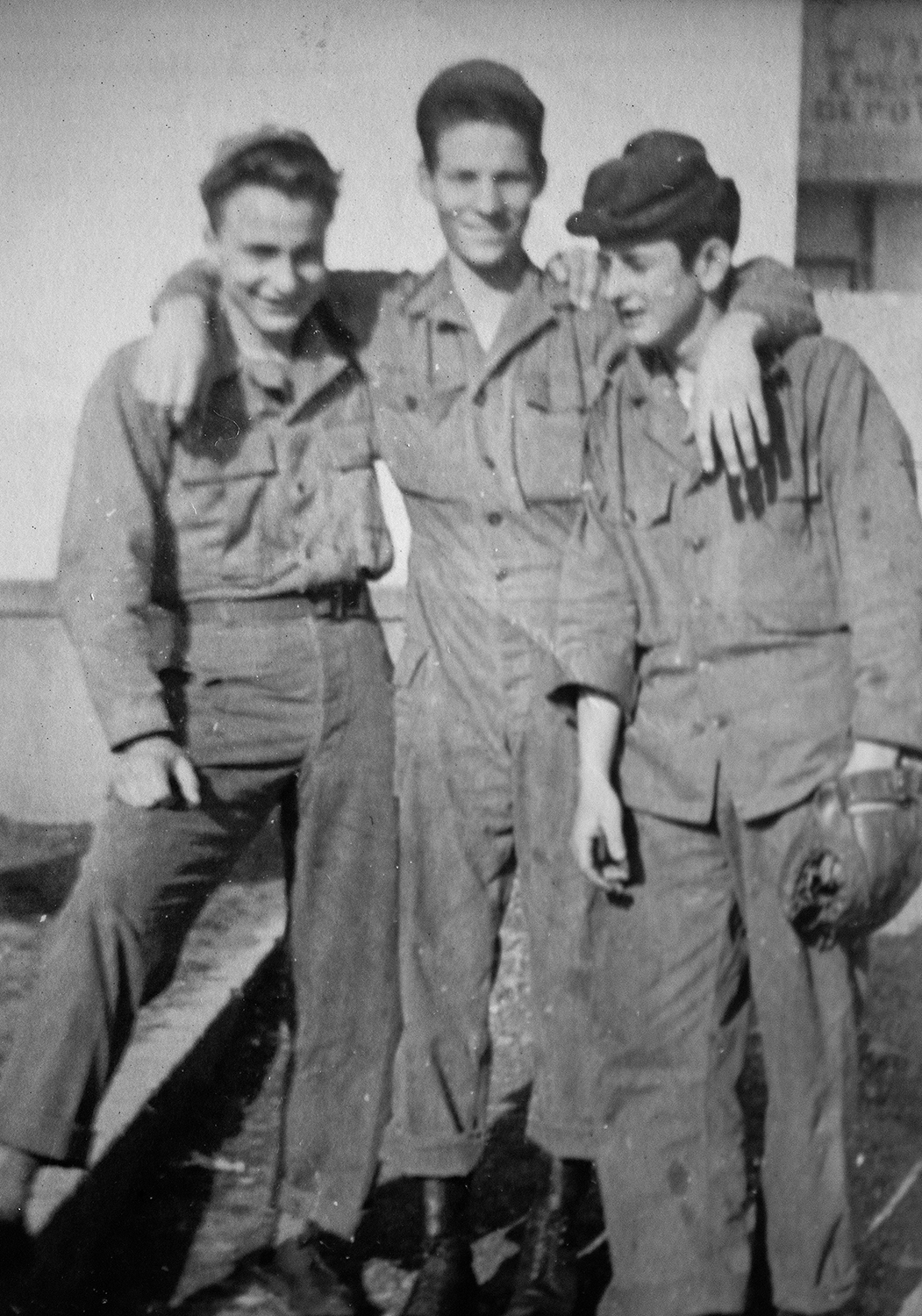

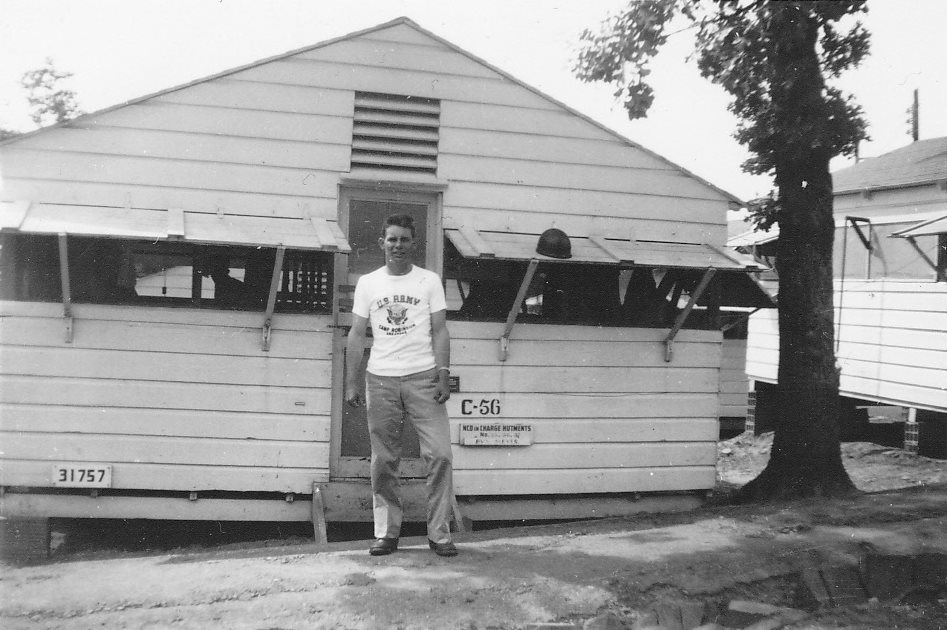

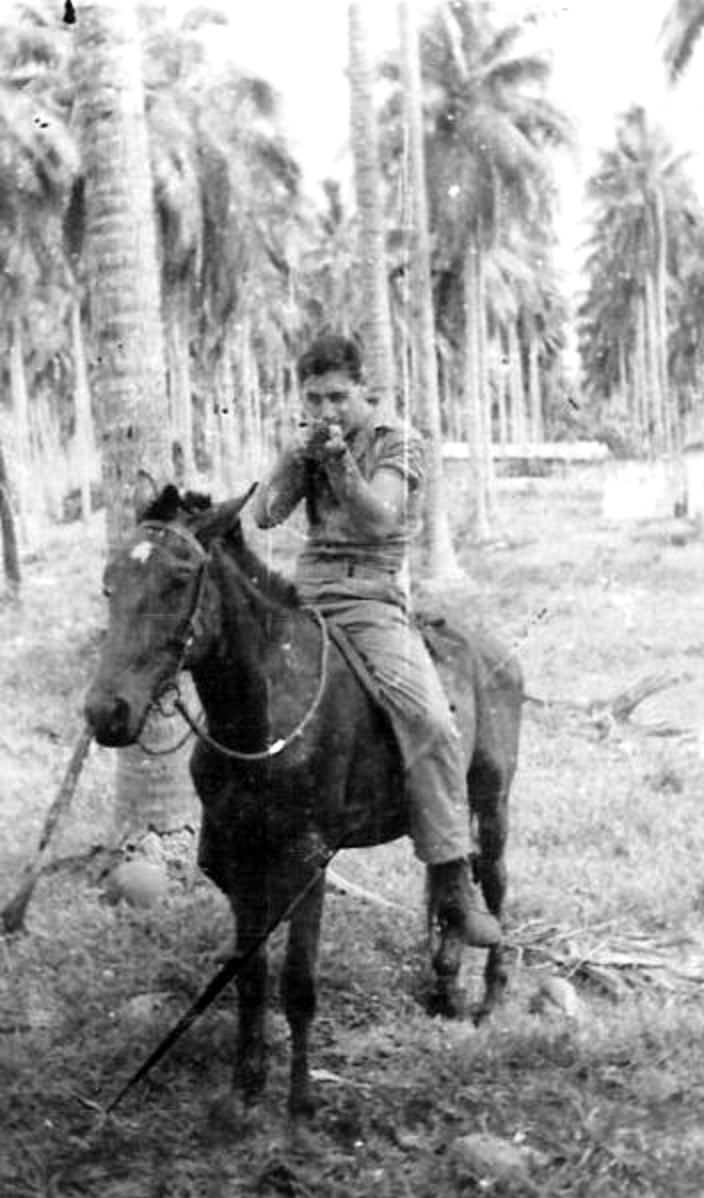

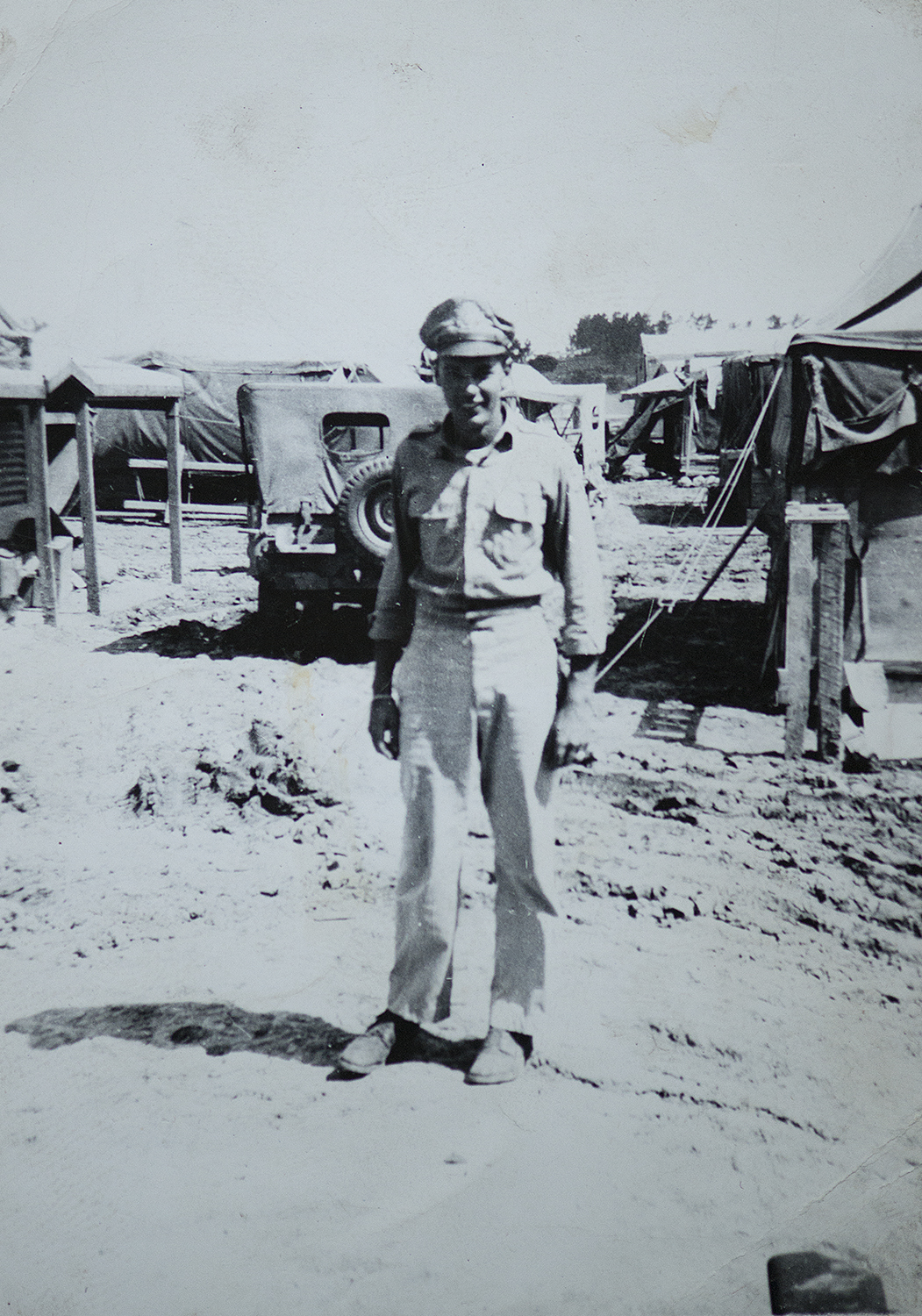

Photos of Bo Gallo in Ledo courtesy of cbi-theater.com

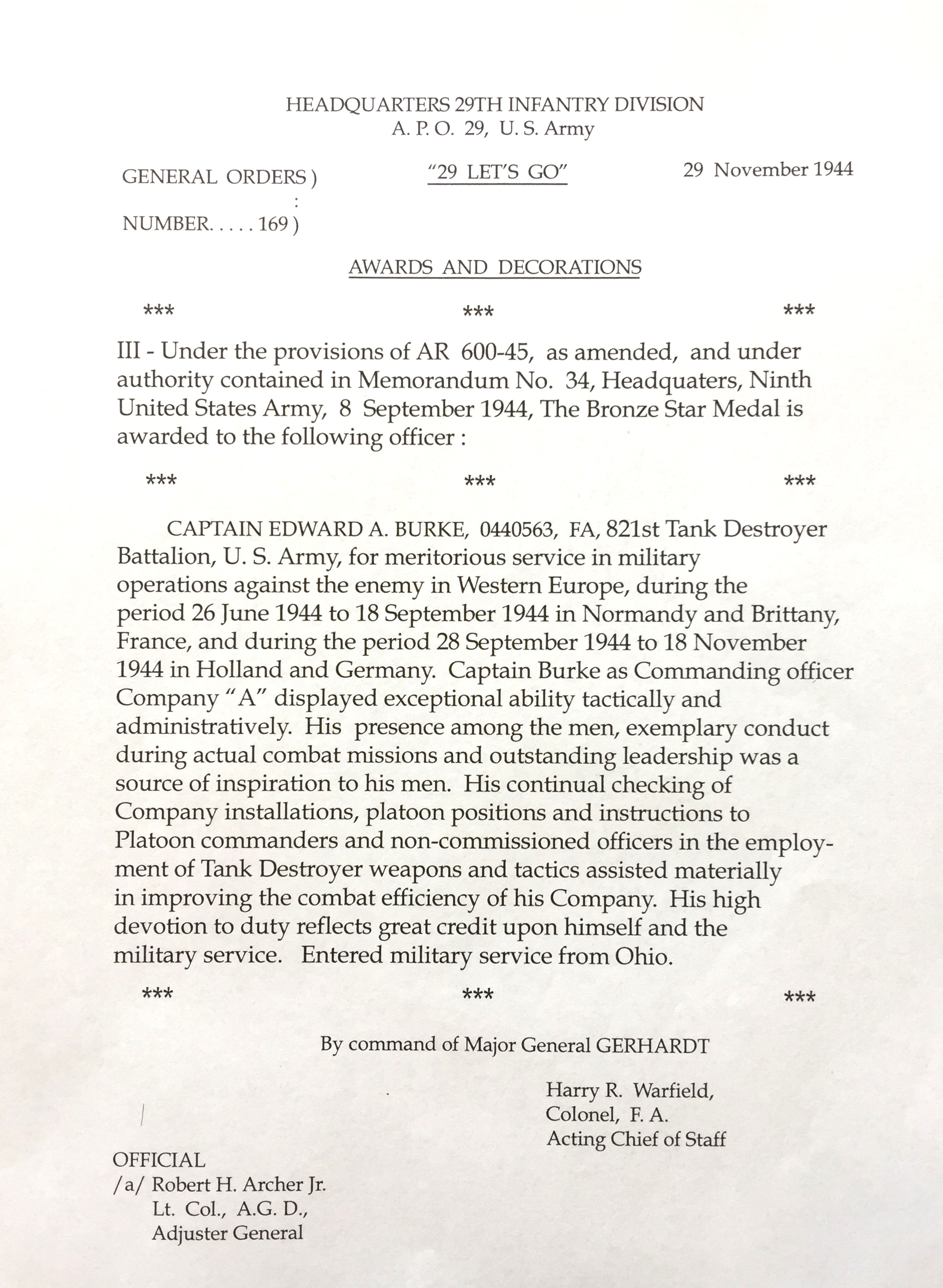

Edward Burke

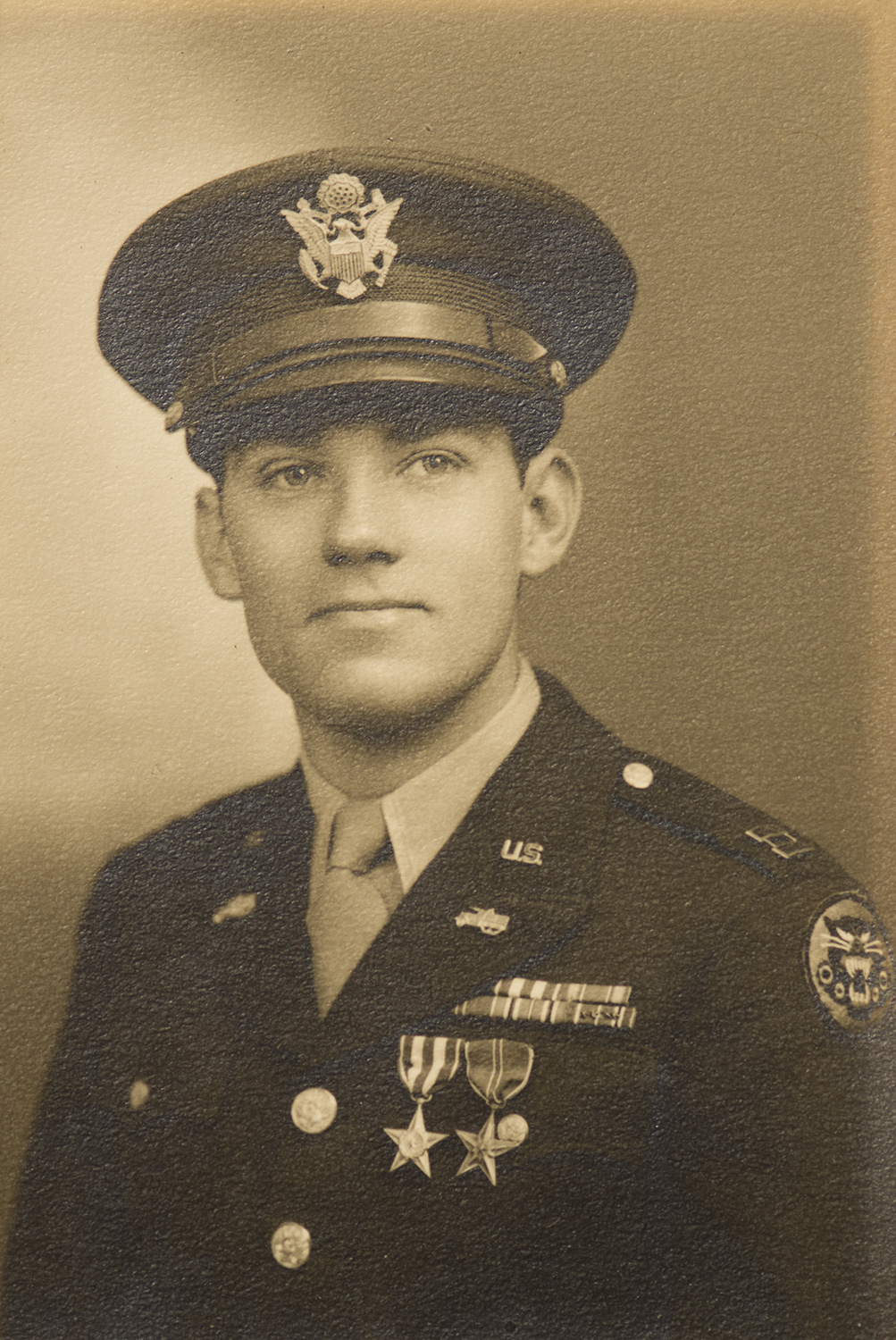

This is a partial account about the adventures of Edward Burke with supporting stories/facts from our interview together and his book titled “From Omaha Beach to the Elbe River.”

"I was born April 9, 1920 in Cincinnati, Ohio. I went to St. Xavier High School, one of the renowned schools in Cincinnati and graduated in the class of 1938. At that time, everything was bad news from Europe, so I thought to myself that I better get some training. All of the major schools had the ROTC program for every branch of the service, the Army, Navy, Air Corps. At the University of Cincinnati, they had the coastal artillery, but I couldn’t seen myself firing 40mm shells while some guy is trying to drop a 500 pound bomb on top of me. I didn’t think that was fair, so I didn’t want any part of that. Xavier had the artillery school and I thought that was fine, that I’d be 10 or 15 miles back behind the lines safe and sound. Boy was I wrong on that! Where I ended up was in the tank destroyers right on the front lines and sometimes ahead of the lines. Xavier had excellent professors. The commander who was in charge, Major Arthur Harper, a West Point graduate, eventually became a Major General on General MacArthur’s staff in the Pacific and the assistant commander was Major Camm, who became a Brigadier General in charge of the 78th Division Artillery in Europe, so we had excellent training. The first two years at Xavier University were compulsory. You had to be physically fit. One of the main things that they looked for was that you didn’t have an over or underbite because if you did you would not be able to control the gas mask mouth piece. If you had flat feet or you were too overweight or too thin or had problems with your eyesight or hearing, you couldn’t be an officer. During our summers while we were in school, we were sent to Fort Knox, which is where we met General Patton and his son in law John Waters. General George Patton was the most prominent American General who was advocating more armored divisions for the U.S. Army. At that time we had only two armored divisions. The 1st Armored was known as “Old Iron Sides” and the 2nd Armored was known as “Hell on Wheels”. Of course we only knew him as a General and not in any close personal contact.

There were about 50 of us that went all of the way through, completing the tests and exams. Since we were artillery, they sent us first to Fort Bragg. Four of us were lucky and we got out first and went to Fort Sill, the premier field artillery school in the summer of 1942. Of course at that time, our forces had taken a terrible beating in North Africa. At this time they were opening up the tank destroyer schools, so they took the top class from Fort Sill, the class I was just in, the top infantry class from Fort Benning and the top class at Camp Riley for the calvary and those were the groups that formed the teaching at Fort Hood. As this was going on they began grabbing us to go to these combat units, but at that time we didn’t know they were going to become combat units. The artillery at Camp Rucker Alabama were just starting and I thought to myself, that’s fine, I’ll be here another 6 months, but the commander of Company A of the 821st who had been there since the beginning got severely ill and he was discharged. I was chosen to be his replacement. At that time, the 821st was in Camp Carson Colorado Springs where they had been training. After I was there for a short time, we were moved to Camp Breckenridge where I got involved with the 101st because they were training close by. Then we went to Myles Standish in December of 1943 and we were there for about a month. In January of 1944, we took off for Europe.

We finally landed in Cardiff, Wales after zig zagging across the North Atlantic to avoid the German submarine wolf packs. Everyone was seasick on that trip. A short distance away at Bristol England we made a stop in the train we were in for the night. The next morning we traveled about 50 miles to Grittleton where we were set up in tents on the grounds of the estate of a wealthy member of the British Aristocracy. Our unit spent a lot of time practicing indirect firing on the Salisbury Plain where we were given a target that we couldn’t see, but we knew where it was on a map. The survey crew would lay a line on the ground with a magnetic bearing with the horizontal direction expressed in degrees east or west of a magnetic north or south direction. The English landscape was not similar to the Normandy coast, so the practice didn’t help us in the Hedgerows. Sometimes we had a forward observer who could see the target and where our rounds were landing and would give us the proper adjustments. As far as the artillery firing was concerned, before we left the US, we spent hours and hours with the crew practicing our firing, so there was no hesitation. The only difficulty with England was that we were very limited in space with the land we were able to practice on. Most of the men in our group were very experienced because they had been in the service for years. At this time we were acting as artillery, we were towed by half tracks or trucks and were similar to an artillery piece. For moving targets, we would go to the East coast to a place called Whitby where there would be boats towing targets 50 yards behind them. Of course this helped us master the skill to judge distance and movement of the tanks that were going to be our eventual problem to deal with once the invasion started.

Most of my men had been to Fort Bragg or Fort Sill Artillery school, so these soldiers were very capable men. They were trained to the utmost. When we gave the orders to fire, there were no problems. While we trained, we used blank ammunition. However, when the big inspectors came along to see if we were up to date, my company was the group chosen to fire and display our unit’s skill level using real ammunition. I had binoculars and I could see the target and I was looking all over to see where the round had hit, but what had happened was my crew hit the target directly, so here I was trying to figure out where it hit so I could give corrections to adjust fire. Fortunately one of the men in my crew said “It’s right on the target!” There were a lot of laughs. We had a lot of practice and we were very proficient in all weapons, including machine guns and rifles.

On the morning of June 6th, the 29th Infantry Division and The Big Red One and attached battalions landed on Omaha Beach with the 116th Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division at Dog Green Beach at the Vierville draw. As the landings took place, in Company A of the 1st Battalion of the 116th Regiment, there were 37 men from Bedford, Virginia. Of these men, 23 were killed on DDay or in the next several days. As they came off the beach and up that hill and started to move inland, they saw the artillery had decimated the beach. The difficulty we had with the Normandy was that the Germans had been there for 4 years. They had time to lay mines where they knew we would have to advance. The Germans also knew exactly where their artillery and mortar rounds would land because they had maps with the actual distance from where their guns were placed to the roads that the Americans would have to advance down. In France, particularly in Normandy, which was the capital for growing crops, the farming families liked to keep their plots of land divided by putting up hedgerows and rocks and this had been going on for hundreds of years, so that stuff was very thick! Another thing that made Normandy difficult was that the Germans had the elevation and distance mapped out among the hedgerows and could drop a round within feet of their predetermined measurements, while we had to go by trial and error by just looking at the maps we were issued. Since we were pushing off of the beach inland, we didn’t have any forward observers, so that made everything a guessing game.

The big problem for our tanks was that we weren’t staying on the roads all of the time, so if our tanks were to push through and over the top of the hedges, their soft underbelly was in plain view of the Germans. After a while, we learned to put some metal prongs on the front of our tank destroyers to help cut through the hedges, but if the Germans were on the other side of that field camouflaged in the next hedgerow, you were exposed and they got you. Of course if you’re towed, like we were at that time, you’re hauling a truck and you have to dismantle everything, dig it out or come off the road where you’re out in the open and susceptible to firing and then reassemble. We were at a disadvantage the entire time in the Normandy hedgerows.

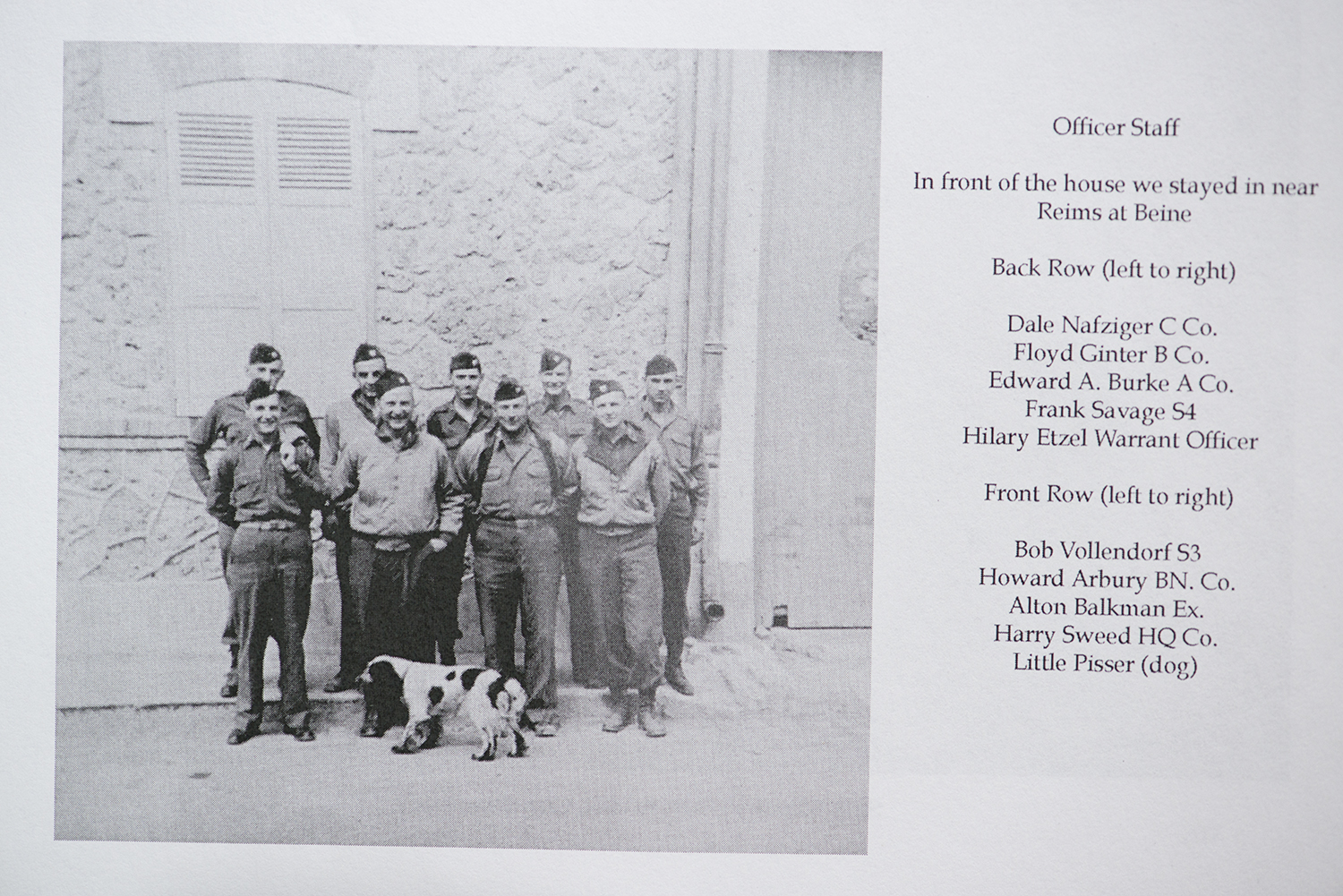

It took us about a month to take St. Lo. The battalion was assigned a certain area on the approach and normally there was a tank destroyer company attached to each regiment, but when there was a large battle, we may all be assigned to one particular area. Normally we would alternate while going into towns so the same company wouldn’t always have to advance in on point. The 29th Infantry Division was pushing in and we were following close behind their regiments. I had 12 artillery pieces in my Company A and we were set up in a defensive position. Before we could advance, we had to send in our reconnaissance platoon to scout and see where our guns could be placed. 1st Lt. Joe Phillipson was the leader of 2nd Platoon and he was your typical gung-ho young soldier. He was a redhead from California, loved to surf and was full of energy. He led the patrol down this sunken road that was about 200 yards out from our position to try and find an opening in the hedge. Platoon Staff Sergeant Grim, Recon Sgt. Dick Smith and Sgt. Edward Brennan followed. Evidently one of them tripped an “S” mine, which we called a “Bouncing Betty”. Phillipson and Grim were killed and Smith was seriously wounded. Sergeant Brennan’s shirt was blown off of his body, but somehow he was not touched. Company A, since we had a greater range of distance with our 76mm guns, fired across crossroads and intersections at night to prevent the Germans from bringing up troops and supplies to their front lines. We captured St. Lo on July 19, 1944. This entire time I was scared to death of stepping on or crawling over a mine. Those things were everywhere.

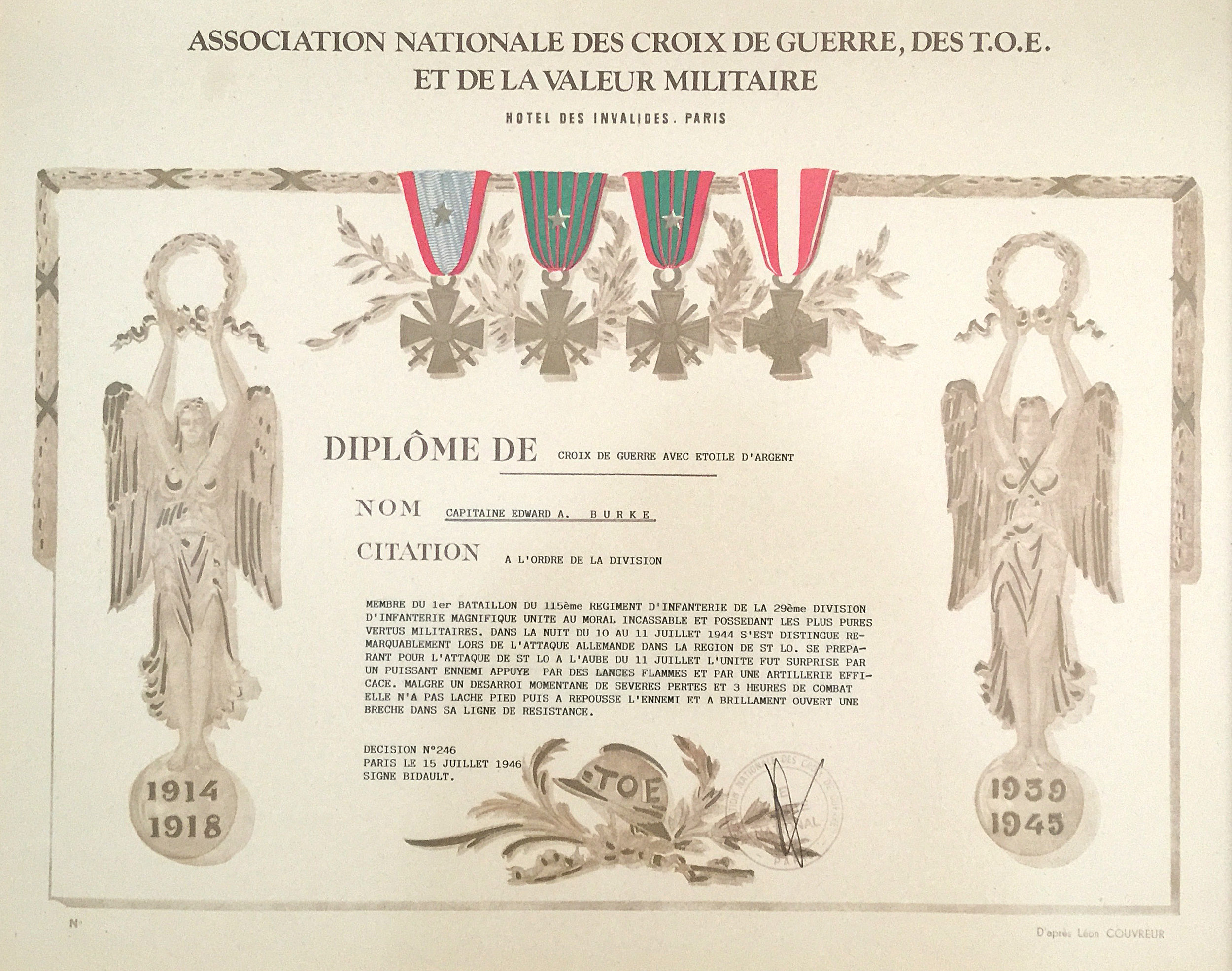

On our way to the city of Vire, we faced heavy German opposition in the little village of Villebaudon, which was at a crossroads. We were at the southwest corner of the intersecting streets going North, South, East, and West at a higher elevation. I was ordered by the regimental commander to put my guns there. The Germans launched a tank and infantry attack on us. I was put at an elevation where the Germans were in a lower position and they began dropping mortars on us. Because of the terrain, I could not depress my guns to fire on the Germans who were firing on us. We were under significant mortar and artillery barrage for what seemed forever and a number of my men were killed and wounded. An artillery concentration was also fired upon the Regimental Headquarters of the 175th Infantry Regiment and a round landed in the command post and killed or wounded nearly all of the staff that were in there. We were able to survive the attack. The battle at Villebaudon was one of the most violent engagements with the Germans that I myself experienced. I was nominated for the French Croix De Guerre Medal for this engagement.

Throughout the engagements at St. Lo, Villeboudon and Vire, we were subject to endless artillery fire and mortar fire. The Germans were set up in depth throughout this entire area of Normandy. Their fire, like I said earlier, was heavy and accurate, while our return fire was nowhere near as accurate. The Germans had the higher ground every single battle and fought in depth. During the day we had to defend the line and during night we had to fall back and act as artillery. That made it tough on us, there was very little sleep.

During the Battle of Brittany we were designated mostly as artillery. Our job was to bottle up all of the Germans that were there defending the submarine bases where the submarine wolf packs that preyed on allied shipping in the Atlantic were held. We were to knock out the forts that had been built up over many years and were impenetrable by bombs being dropped by our Air Force. The 29th Artillery and our Tank Destroyer Battalion dropped thousands of rounds of shells into the forts, but somehow had to avoid damaging the port so it could eventually be used for our supply ships to land. After 26 days of intense fighting, Fortress Brest surrendered.

Since the 29th Infantry Division and attached units had been engaged in combat since D Day, we thought that we might be able to get a leave or furlough back to England, but before that happened, the 29th Division was ordered to prepare to move to Germany where it was to reinforce the First Army in its attack on the Siegfried Line. Our 76mm guns, which were towed by half tracks and trucks, were part of the Motor Group, the infantry traveled by train. After making night stops in Rennes, Chartres and St. Quentin, we arrived in Heerlen, Holland three days later on September 28, 1944. On October 1, 1944, while we were in the rest area of Heerlen, the Battalion issued a report covering the period of June 30, 1944 to September 18, 1944 inclusive. There was also an “Awards and Decorations” section and I learned that I was recommended for the Croix De Guerre for exceptionally meritorious service in direct support of military operations against the enemy in Normandy and Brittany, France. I think that award was based upon the terrific battles that Co. A had in taking the cities and villages of St. Lo, Vire, and Villebaudon.

My Company A, 821st T.D. left Heerlen and then moved to Brunssum, Holland, where we would fire at night at crossroads with interdictory and harassing fire to prevent the Germans from bringing up ammunition, petrol and other supplies to their front lines.

Once we reached Germany, the best thing was that we were able to stay in homes. First we had to check to make sure there weren’t any boobytraps set up that could wound or kill us. The civilians were not happy to see us there. Many had dug trenches around their farms to protect their land and each small town was a ferocious battle.

During Christmas of 1944 we were in sort of a lull. “On Christmas Eve it was a very cold day. Snow covered the hard frozen ground and shell holes. It covered the pine trees, hedges and bushes heavily with frost and they sparkled in the sunlight. We were mainly in a holding position until the troops south of us could bring their front line parallel with us on The Roer River. Down by the River, several of the outposts reported they could hear church bells ringing and German voices singing across the river in Julich. At 4:00 in the morning, the night ceased to be silent. Machine guns roared and cracked and tracers ran over Julich while our mortars crashed into the roofless city in a planned gun “demonstration”, but that didn’t last long and 10 minutes later, all was quiet and our outpost guards reported no other activity.” Christmas Day was cold. Our tank destroyer front was quiet and uneventful, but it brought clearing skies and allied planes, which had been kept on the ground for days because of the foggy weather, were now able to get out in great force. Our Headquarters Platoon and most of the First Platoon of Co. A 821st T.D. Battalion were in Durboslar. Our mess section and cooks prepared a marvelous turkey dinner. Co. B and C had hidden their tanks in barns that were close to The Roer River. Nearby there was an old German Catholic Church and it was filled with soldiers for Midnight Mass. There I met Frank Bill whose family I knew in Price Hill and he lived a couple blocks from me in Cincinnati.”

We had reached the Roer river before any other division. Our job there was to fire interdictory and harassing fire across the Roer River. As you came farther South, you came into cavalry units that were buffers between us and the First Army.

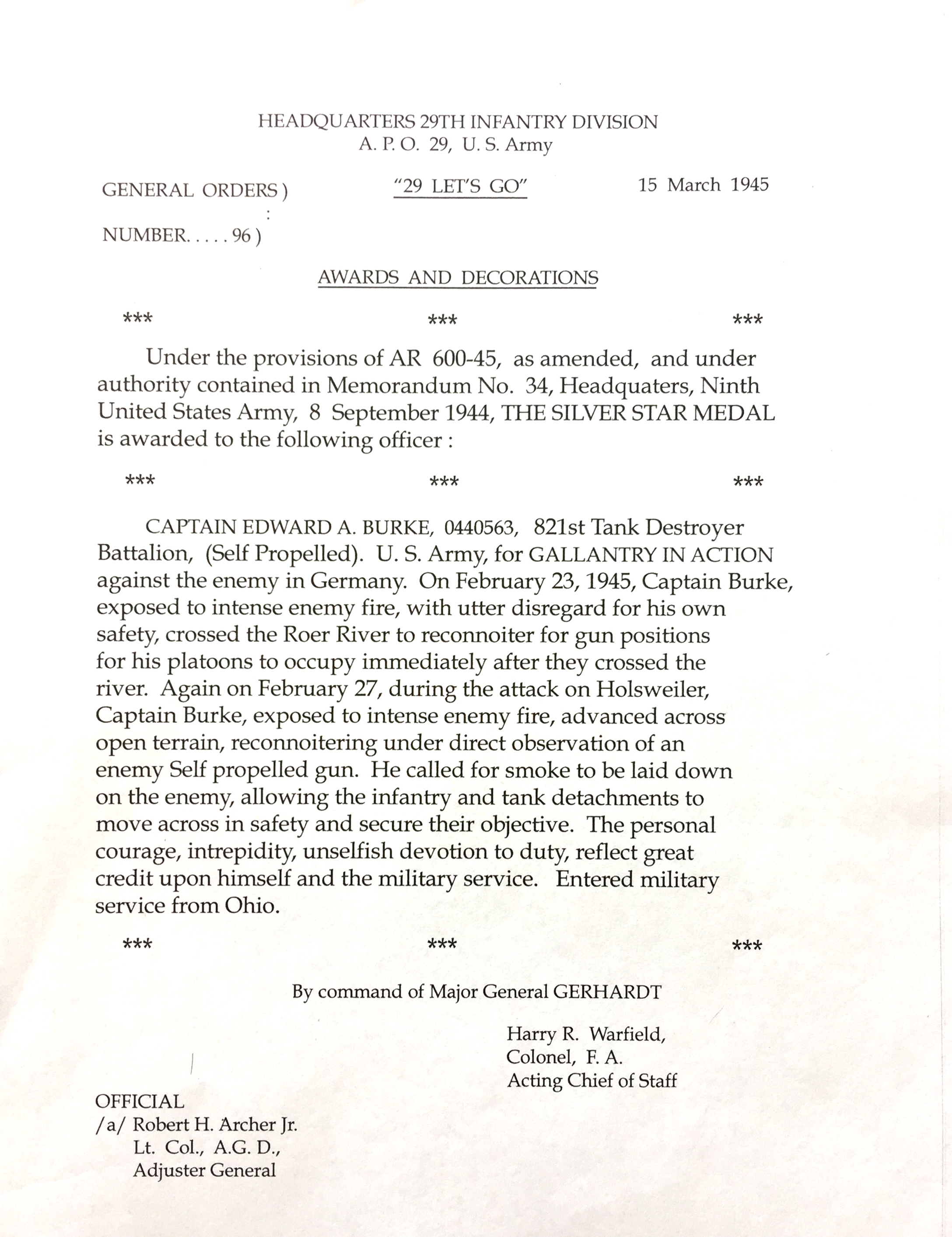

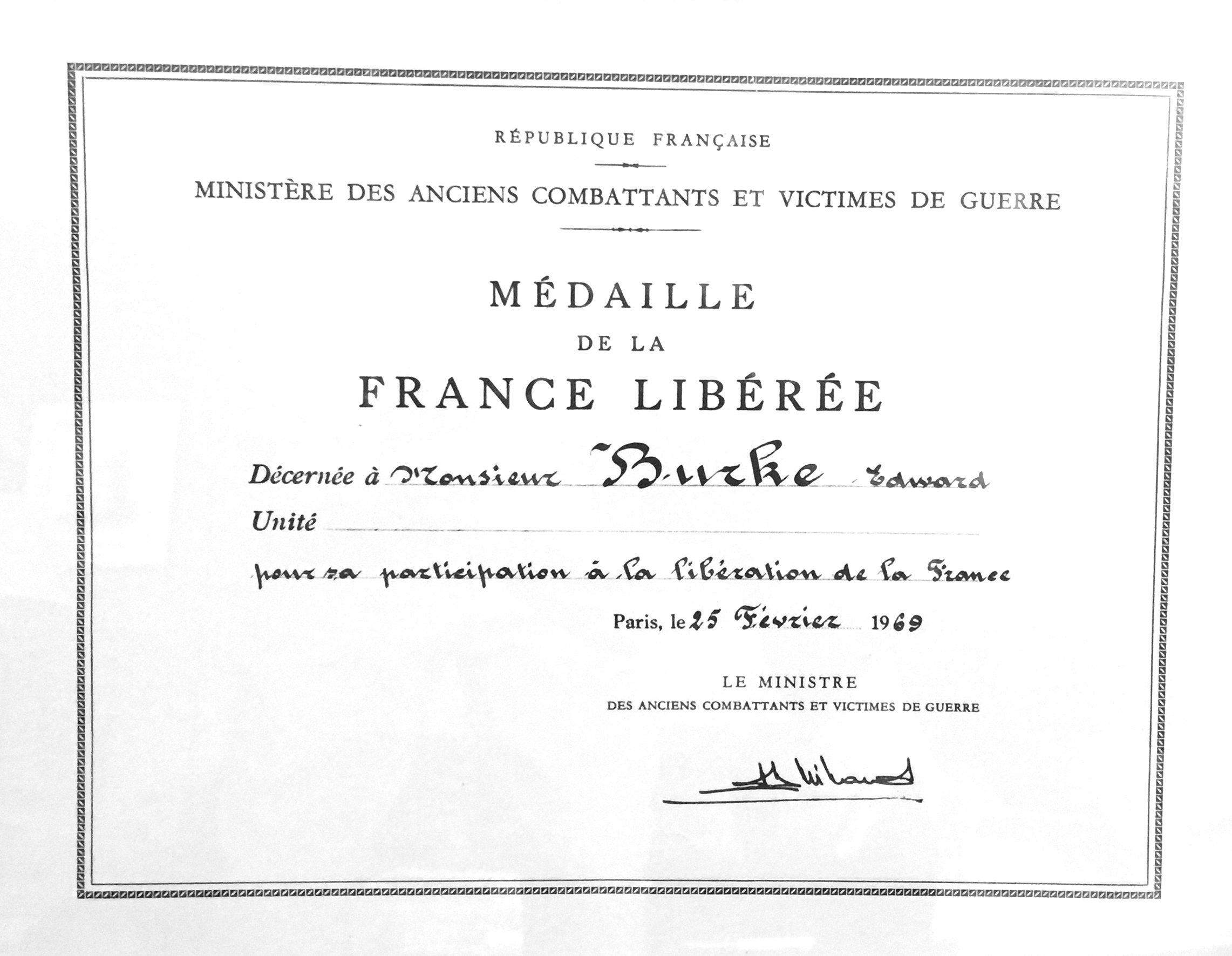

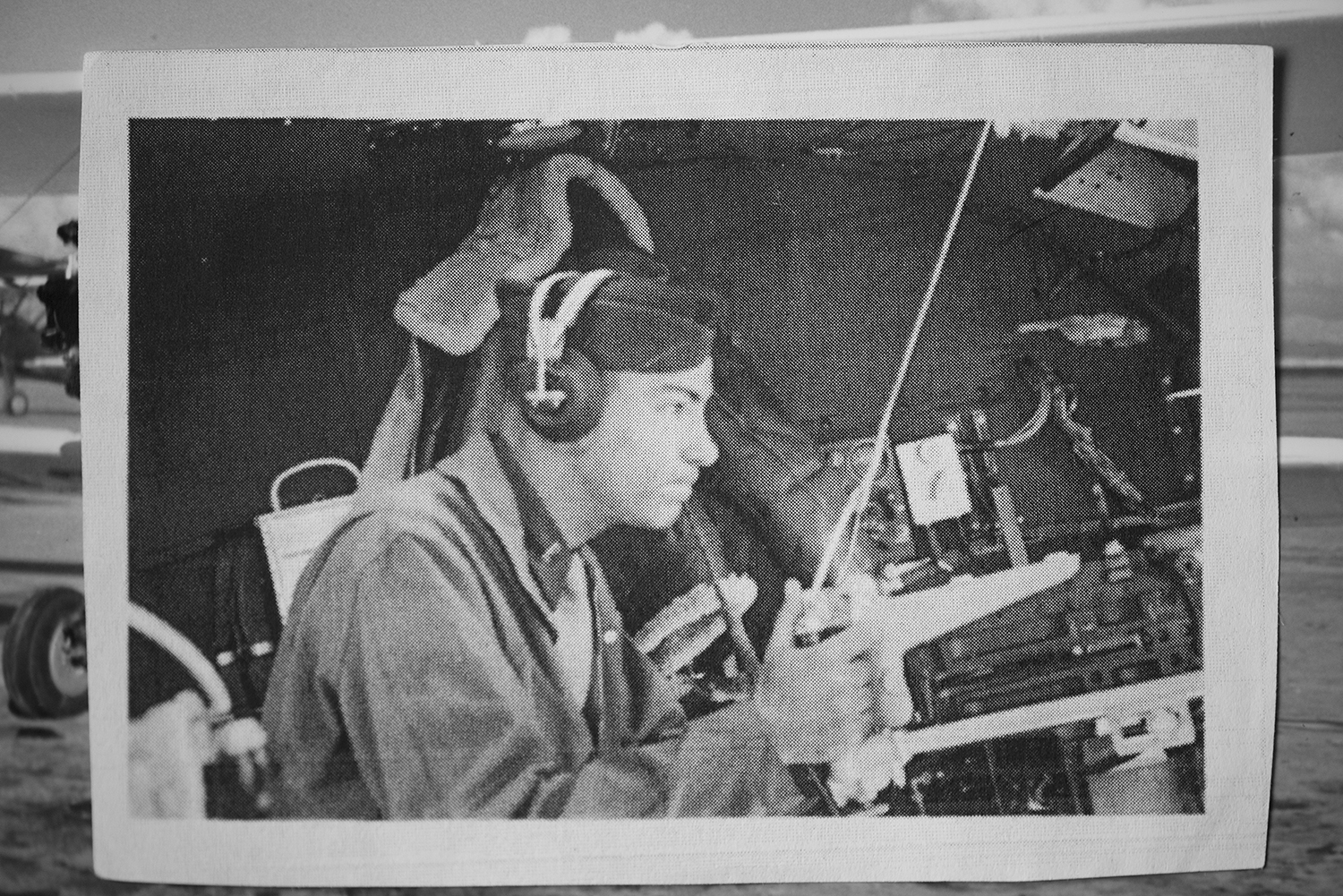

For the attack on Julich, my job was to lead the 821st Tank Destroyer Battalion across the river. The crossing was scheduled for February 23, 1945. Since I was the senior captain, I was the one to reconnoiter for my Tank Destroyers to lead the way over the pontoon bridges, which were to be erected as soon as possible. The Roer River was in flood stage. What had happened was that the German’s were trying to flood that area so we couldn’t cross to the Rhine Plain. They bombed the dam and failed, but the damage was enough to cause the water to flow out slowly, which worked to their advantage. The river was in flood stage for over a month! I didn’t know what the area was like where my tank destroyers would be advancing, so the battalion commander ordered me to go over there and reconnoiter the terrain. The pilot of our regimental plane, whom I had known since artillery school at Fort Sill back in the states and I had become good friends. I got orders to fly along the west bank to determine where the best locations would be for my M-10 Tank Destroyers to protect the infantry from German tanks. While we were flying, I could see the tank tracks in the snow and knew where the tanks were located in the forest. They were big tracks, so we knew they were Tiger and Panther tanks. I had an idea of how I wanted to get there, but I didn’t know what it was going to actually be like on land. When the time came for me to cross and scout positions, over ten thousand rounds had been fired by American Artillery. Following that, a smoke screen was fired on the east bank of the river. My job was to cross in a little row boat with two engineers who would paddle me over where I would scout locations to put my Tank Destroyers to protect soldiers of the 115th, 116th and 175th Regiments once they crossed. The bank on the east side of the river was somewhat steep which helped protect me from German fire, but they had my every move zeroed in. After studying the maps and aerial photos for the last week, I had a pretty good idea where I was located. My biggest fear was stepping on a mine. I hoped that all of the artillery that had been pounding that area had destroyed all of the mines, but you know that never happens. I couldn’t do too much walking because the law of averages would call on me to get captured or step on a mine that I couldn’t see and I couldn’t use a flashlight because I’d give away my position. My job was to determine, based on the terrain, where I could deploy my Tank Destroyers to destroy any German Tanks that would attack. I tried to follow what I thought was a beaten path somewhere along the line that may have been caused by people fishing in the river. The Germans had patrols along the bank and we had been there for over a month since the Battle of the Bulge. We had been giving them tons of fire, so I hoped the Germans had cleared out of there. As I reached the city, I saw a partially destroyed church, which reminded me of my high school days where the students prayed for the soldiers and I’m sure they were praying for me. The church gave me some protection and that’s when I saw the area where my Tank Destroyers could advance once they crossed the river. When I found the protection of the solid stone walls of the church, I regarded it as a good omen. I was particularly concerned about the slope nearby because the Germans could have guns dug in there. What I wanted to do was go around on the flank, I didn’t want to come up the hill and expose my tanks. Later on while we were attacking, one of the tanks did this and was lost. On my way back from scouting, I tried my best to retrace the steps along the same route I had advanced from The Roer River. When I got back to the river, the engineers were building a footbridge so they could get their material across to start putting together a larger pontoon bridge. The infantry would come across that foot bridge. There was a body of a soldier who had been killed as he tried to cross the bridge. I had to step over his body to get back to the west bank. After I had made it back safely, a German mortar barrage cut the footbridge in two while medics were carrying wounded across. I was later awarded the Silver Star for my crossing the Roer River under heavy artillery fire to reconnoiter positions for my tank destroyers.

At about noon on February 24, 1945, the Bailey Bridge just north of Julich was completed and Company A crossed the Roer and occupied direct fire positions north of Broich on the east side of the Roer. Company A’s tank destroyers had been waiting for the pontoon bridge to be completed. From Broich, we turned toward the town of Müchen-Gladbach.

We had a terrific battle at München-Gladbach. It took us four days to capture the town. It was the biggest town that had been captured by Allied forces and was also the hometown of Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, so the fighting was extremely fierce there. The central point of interest was Schloss Rheydt, a sixteenth century castle and once the town was taken, General Gerhardt played host to the company commanders of the division and attached battalions and made a toast with champagne from the wine cellar. The next day, something very ironic happened, in the home of Germany’s most prominent Jew Persecutor, Goebbels, Hebrew services were conducted by one of the 29th Infantry Division’s chaplains, Manuel Poliakoff, in a room decorated with the Nazi Swastika.